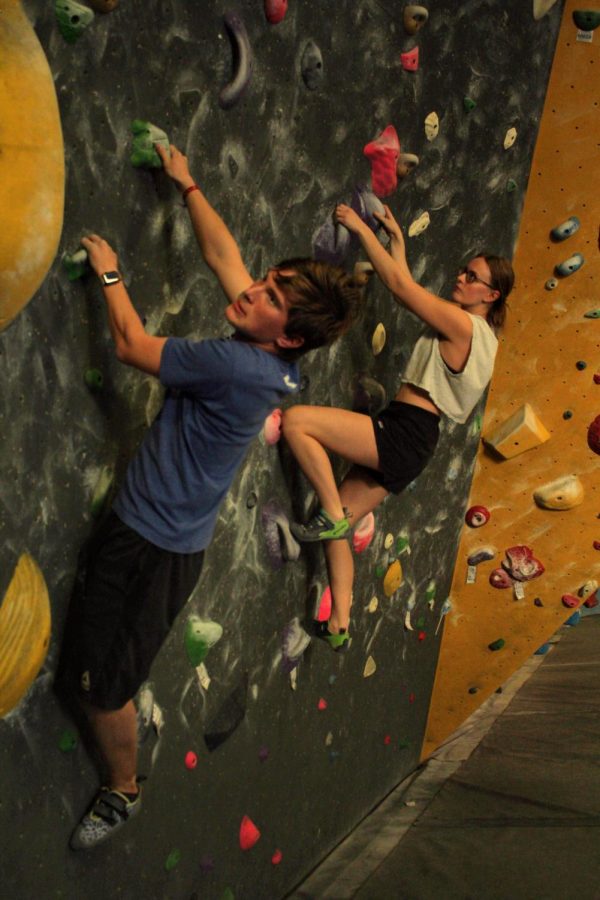

Unharnessed

Without any restraints, bouldering unlocks a new sense of freedom.

Photos by Bella Tilford

Bright orange with caution. My white dusted hand extends up, reaching as far as my arm can stretch. A single finger grips on to the obscure and grainy object with all its might, struggling to stay on. I adjust, continuing to pull my weight up. To my left somebody slips, falling to the crash mats below. I keep my eyes locked in—they reflect my goals, my challenges, my climb.

I think of rock climbing as a story through life. I try to plan out the route as best as possible before I begin, but I will never truly know what it’s like until I’m on the wall. I must push myself past that fear of the unknown, past the fear of the risk that awaits. I must be capable of pushing the boundaries.

Balance is the key. With every choice, I learn to trust in myself and my abilities. I allow my body to take control of my movements, engulfing myself in the present. I flow from hold to hold, moving deliberately and with a powerful delicacy. I feel a sense of safety within myself on the wall and though I go up solo, I never feel alone. Each hold is a hand reaching out to guide me, a stepping stone to rise up on.

I climb freely up the wall, no ropes or harnesses there to hold me. This is called bouldering, a specific form of rock climbing that usually involves shorter walls with more intricate holds. In the rock climbing world, boulder climbs are called “problems,” which is fitting because they bring about a lot of struggles. When I first walk up to the wall, I try to envision my moves before starting. The first try almost never works out; there is always some surprise hidden within the depths of the holds. It’s frustrating to try and try again, but that’s also part of the process.

I am hyper-aware of my body while bouldering, the words “scared,” “high,” “misstep” echoing through my brain. I have to switch them off to find comfort. Maybe the risk is too high, but I yearn to reach the top. I let go of the fear, turning my problems into momentum. I climb to feel confidence in myself, to know that I am capable of looking past fear. I am free on the wall, relying purely on myself.

A young man, barely older than myself, sits on the chalk covered mats of Climb NuLu, a bouldering facility in Louisville. He stares at the wall towering above him, making a mental note of the route. He views climbing as a puzzle, each colored hold a different piece to try and fit together. A seemingly normal task of distributing his body weight is much harder for himself than other climbers, yet he knows there is always a way. Standing up from the mats, he hops over to the wall, only one leg there to support him.

His name is Grayson Hume, a 17-year-old climber, skier, and student. Adopted from Ukraine when he was a baby, he grew up in Louisville spending much of his childhood exploring the outdoors and attending local summer camps. Like any other kid, he took interest in climbing trees— finding paths up uneven and swaying limbs. Hume stood a little taller at the tops of trees, away from all the rude comments and stares of other kids his age.

Born with Proximal Femoral Focal Deficiency, a rare condition also known as PFFD, Hume had his right leg amputated at the age of two. PFFD affects about one in every 200,000 children around the world and Hume was born with the most severe stage: stage four. Learning to walk without a femur bone imposed many issues, leaving his parents to make the tough decision of amputating his leg.

Hume explained how he always felt out of place, like he had a sixth sense that could detect people glancing at him. His leg was always the first thing people saw and the last subject they would bring up in fear of making him uncomfortable. When he was younger this especially affected him because he didn’t want to be seen as different, but he had grown to see his missing leg as part of his identity. To Hume, it was the sole factor that defined him and had detrimental effects on his body image.

When Hume first walked into Climb NuLu four years ago, he instantly fell in love with it.

“They don’t look at me like I’m handicapped,” Hume said. The gym is his safe place because everyone there is connected through a shared passion for climbing.

When someone falls, others are there to help motivate them. They celebrate successes and work around their defeats. Walking into the gym, Hume clears his mind of everything else in his life, focusing solely on what is in front of him. In doing so, he can climb for the beauty of letting go.

Hume recalled a fellow climber helping him with a route one day. They talked for a while, giving each other tips and guidance. This happens quite often at the gym — meeting someone new and working on a problem together. At one point the climber informed Hume that a company called Evolv makes prosthetics specifically for climbing. Hume’s regular prosthetic leg doesn’t work for bouldering, so he is forced to go without it. He has learned to move up the wall in his own way, something that now comes naturally to him. Instead of moving one hand then the opposite foot, he moves one hand then the other followed by hopping his left foot up. Hume is now getting a climbing foot made and looks forward to seeing how far he can progress with the new attachment.

“What the climbing community understands is that everybody goes through stuff,” Hume said. “People talk different, people look different, but no matter what we are all connected through climbing and that’s what we’re there to do.”

Outside of Climb NuLu, not everyone is as accepting. In the summer of 2020, Hume stood in his khaki shorts and red polo, walking from car to car taking drive-thru orders at Chick-fil-A. The shorts exposed his prosthetic and limp along with it. “Cripple,” called out a group of teenage boys from inside their car. The hot summer air made Hume’s shift at Chick-fil-A hard enough; he didn’t need disrespectful comments added to the mix.

Hume has learned to handle these situations well, but they still hurt to hear. He told the boys it’s not fair to make assumptions about his abilities before asking about his story.

“It was more of that disappointment in society that really stuck with me,” Hume said.

Hume has learned to seek his true identity, one separate from how he looks on the outside. For a long time he took the name-calling to heart, allowing the comments to bury inside him.

“There was a point when it bothered me a lot because of the stares, the doubts,” Hume said. “When I walked into a building I had to prove myself to everybody else.”

Hume said the jokes don’t offend him anymore because they aren’t attacking his character. He understands that people are going to be mean, but that it is out of his control.

“I’m never uncomfortable talking about my story because it’s a story that I am proud of because it’s a part of me, but it doesn’t define me,” Hume said.

His climb is towards self acceptance, a journey that is ever-evolving. The moment Hume stepped through the doors of Climb NuLu, he had taken off his harness.

“There, I don’t really feel out of place ever because number one they don’t look at me any different and they don’t look at me like I’m handicapped,” Hume said. “They give me the tools to do rock climbing, they want to encourage me, and help out in any way they can.”

He didn’t allow for others to hold him back or tell him that he wasn’t qualified to climb. He is as much of a climber as the person next to him, as capable of achieving his goals, and as willing as ever to try. Hume climbs to prove to himself he is more than just a person without a leg, that he is no different than anyone else, because he isn’t.

“I was purposely designed,” Hume said.

We both begin with the same goal in mind. From an outside perspective, the same destination. Though our physical differences change the appearance of our climb we have both found our place on the wall.

The fear has subsided as I have settled into my climb. I continue onward, moving up the wall with my new found confidence. The final orange hold is in sight, all I have to do is grasp on. But, I am still cautious, the added height of the final reach makes it that much more difficult. One-two- and by three I am pushing off my right foot and extending up. A deep exhale followed by a fulfilled grin emerges. I jump down from the top, no harness there to slow my fall. No harness needed, for I have learned to place my struggles on small footholds and to trust they will hold me there.

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.

Lily Cashman is a senior and the Editor-in-Chief of On The Record. In her third year on staff she is excited to continue providing...