Up until that point, Isaiah Woodson had been sitting with his eyes closed while discussion continued around him. His fingers tapped lightly on a bongo resting in his lap. He sat passively as Jalen Posey (16), the president of Central Magnet Career Academy’s Black Student Union (BSU), launched into another confident and unapologetic speech.

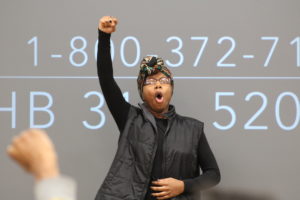

“If you are not of African descent, you can still come, just be prepared to drink from the black water source,” Posey said. “This isn’t a diversity club: this is a Black Student Union. So come if you can drink the Flint, Michigan water.”

As Woodson, a member of the University of Louisville’s (U of L) Association of Black Students, responded, his eyes remained closed, a slight smile perched on his lips.

“You know what? I disagree, ‘cause humans originated from Africa. So we’re all from African descent,” Woodson said.

Everyone in the circle turned to look at Woodson, eyes wide with surprise, but then Brandon Porter (17), a Butler Traditional High School student, said, “It’s true. Just a lot of people don’t want to believe that. All men, all humans come from one place: Africa.”

Each spoke differently, some with a quiet passion and others with outright zeal, discussing how each handles their respective BSUs, clubs that educate, equip, and empower black students to make a difference in their community. A red, black and green banner – the colors of Africa – hung off the corner of a bookshelf, hinting at their purpose. Besides that, the room was sparsely decorated.

Each of the six students represented a different school’s club: the high schools Louisville Male, Central, Butler, and duPont Manual, along with the University of Louisville. They talked about their respective BSUs, debating their feelings on diversity and discussing the range of people they saw within their own meetings.

Every month, these six teenagers from different Louisville BSUs and others gather at a shared office building located near the Portland neighborhood as an umbrella organization, Citywide BSU, created last year to continue these discussions.

The school BSU leaders use the city-wide BSU as a tool to help them organize cohesively, overcome obstacles as a group, and inspire others to start BSUs at schools that don’t have anything else in common. According to the Central BSU’s mission statement, BSUs attempt to further their understanding of their own identities while promoting cultural activities and educational enhancements. Ahmaad Edmund (18) inherited the part of the building used by Citywide BSU from his grandfather and shares the rest of it with the Afrikan Village Group of Louisville, who rents it to other organizations around the city.

Among Louisville public schools, Waggener Traditional High School, Iroquois High School, Ballard High School, Manual, Male, and Central have BSUs. Half of these BSUs find their origins in Citywide BSU founded by Edmund, who also acts as the president of Male’s BSU, on Feb. 19, 2016.

“I made a phone call to a local activist in the city, and I was just commending her on her efforts,” Edmund said. “We talked for a while and somehow or another, an idea came up that we should get all the BSUs in JCPS in one room, so I said let’s get the city-wide BSU together made up of all the different high schools, and this could be our headquarters.”

Aside from working directly in schools, the students within the city-wide BSU are also responsible for holding events available to people from all over Louisville, targeting people of many different age groups. One program that the BSU participates in is called Books and Breakfast, an event that aims to help the entire black Louisville community through discussion and a complimentary breakfast.

Aside from working directly in schools, the students within the city-wide BSU are also responsible for holding events available to people from all over Louisville, targeting people of many different age groups. One program that the BSU participates in is called Books and Breakfast, an event that aims to help the entire black Louisville community through discussion and a complimentary breakfast.

“People need one, food, and two, knowledge,” Posey said. “The black community gets to leave with a full belly and a full backpack of books.”

Citywide BSU also promotes other community gatherings, such as the Kwanzaa Celebration held at the Shawnee Cultural Community Center for five days between Christmas Day and New Year’s Eve. Various local organizations agreed to host the event including The Original Village, an independently owned restaurant, and Hood 2 Hood, an activist movement fighting violence in the Louisville area.

“Everyone there embraced our rich culture by wearing dashikis, listening to the beating of the djembe drums, and accessing multiple black businesses,” said Kara Cunningham (17), vice president of Male’s BSU.

Individual school BSUs also have a hand in organizing community events. At Manual, for example, the BSU participates in everything from political events to youth outreach programs. Last summer, the Manual BSU organized a protest event.

“We had a Black Lives Matter vigil which became more like a march,” said Lydia Mason (18), president of Manual’s BSU. The vigil took place on July 17.

Manual’s BSU was founded in 2014 as the first BSU in JCPS. Mason listed literary nights, poetry slams, and a mentoring program with the Boys and Girls Club in Newburg as some of their successes.

Mason stressed that though many protests were sparked by President Donald Trump’s inauguration, the problems they address have existed long before he was sworn in.

“Black people being treated differently on the basis of their skin color – that’s not a new thing. Donald Trump didn’t invent that,” Mason said. “This presidency just makes people who aren’t normally aware of it aware because it’s so blatant right now.”

Mason and her student group also want their BSU to benefit the Manual community specifically. With 64 percent white students and 36 percent nonwhite students, Manual’s population roughly mirrors the Louisville area, which is 70 percent white and 30 percent nonwhite. However, only 13 percent of Manual’s students are black, while 23 percent of the city’s population is black.

Regardless of the breakdown, the existence of nonwhite populations does

not necessarily make a school “diverse.”

Mason said that the BSU “creates a more diverse environment.”

“When I say diverse, I mean that it increases understanding across different backgrounds,” Mason said. “But the BSU has helped to make people aware of the issues that black people face and that black students face.”

However, the biggest obstacle that many students face comes before organizing these large-scale events and their own school meetings. Rallying enough support to start a BSU in the first place is often difficult; some students hoping to start their own find it nearly impossible to recruit a faculty or staff member willing to sponsor the meetings.

“Trying to get support – that’s the main thing,” Porter said. “It’s hard trying to find at least one person and have support from that person. Teachers won’t stay after because they have other things to do like grades, sports.”

JCPS provides stipends for sponsors and coaches of some extracurricular activities such as sports, debate, and yearbook, but not for clubs like BSU.

This may be one contributing factor

to Porter’s trouble in finding the right

sponsor – a search that he says spanned over three months.

Pleasure Ridge Park High School (PRP) BSU students say they had this very problem before finding its sponsor, Latisha Sutton, who teaches math and also sponsors PRP’s step team.

“Trying to find a sponsor for the BSU was tremendously difficult considering there are only two black teachers at PRP,” said Jailen Leavell (17), founder of PRP’s BSU.

Though white teachers can sponsor BSUs, students hoping to start the club say they prefer a teacher they see as identifying with the same struggles. But having a black sponsor isn’t a requirement, as evidenced by Manual’s sponsor James Miller, a white teacher in Manual’s Journalism & Communication magnet program.

“I really enjoy sponsoring the BSU,” Miller said. “The students approached me a couple years ago and asked me to be the sponsor. I’m there for them. If they want me to be the sponsor, I’ll continue to be the sponsor, but if they want to get another, that’s not going to hurt my feelings. They should have a sponsor that’s going to do what they want and need.”

While Miller and much of the Manual student population were receptive to the idea, not every stakeholder in district schools was receptive towards a club aimed at a specific minority group.

Leavell – who said he encountered skepticism from students, teachers, and parents – said the reason behind creating the PRP BSU was to educate his peers, make them think differently, and remove racial stigmas.

“If they learn about the systemic issues that are keeping them oppressed, if they know about the school to prison pipeline, or even if they just learn their true history, pre-slavery, it could change their whole mindset on life,” Leavell said.

Citywide BSU addressed this problem by organizing special showings of “13th,” a Netflix documentary about the U.S. prison industry and its impact on African-Americans, during school BSU meetings across the city.

The students say that discussion generated by this film is just one of the many ways Citywide BSU acts as a forum to compare and contrast ideas, to argue and agree, to shape all of the thoughts and plans mulling around in students’ heads. Without the support of their union members, they believe making change would be a far more daunting task. With it, according to Edmund, change is far more possible. That promise gave Edmund the courage he needed to start one at his own school.

“I thought I was gonna have to go to the ER because it was just so many people,” Edmund said about the first meeting he organized at Male. “I was taken from the present to the future. I saw something that I had never seen before. And that was the solution.”

Edmund can recall how he felt walking down the halls of Male as he went from class to class before he’d even had his first meeting. He remembered the history; he remembered that no black students had been admitted to Male until 1950. He prayed that he would get the support that he needed to get the BSU up and running.

“And sure enough,” Edmund said, “we did.” •