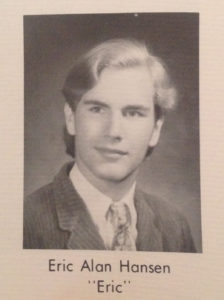

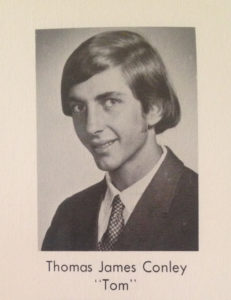

→Westport high schoolers Eric Hansen and Tom Conley sat on Conley’s porch on a fall day in Louisville, tired of endless school rules. Tired of being told to cut their hair to “traditional” lengths. Tired of the draft looming over their heads. Tired of not being able to do anything about it. They wanted to have a say in what was going on – and they knew they weren’t the only ones.

But it was 1968. They didn’t have cell phones or any way to communicate outside of face-to-face conversation and landline phone calls. They didn’t have Facebook to organize events or other social media for fast communication and planning.

Neither were speaking, but they were both thinking about the countless cases they’d seen of boys not being allowed to grow out their hair past their ears and girls not being allowed to wear pants, because both apparently served as too much of a distraction to the school environment. Just a few  days ago they had seen someone expelled because of his hair.

days ago they had seen someone expelled because of his hair.

The sounds of falling leaves and radio static filled the air as an all-too-familiar voice reported the daily updates on the Vietnam War. The death toll was growing higher and higher every day. All throughout high school they had sat silently through dress code issues, war crimes and injustices, and other situations that, to them, didn’t seem fair.

“We should have a group,” Hansen said, and he wasn’t talking about a radical organization of war protesters or even an active educational reform group – though both were similar to what FAIR would one day become. He was talking about a group of young men and women that would get together to discuss local, national, and global issues and propose steps towards progress.

Conley considered this for a moment and agreed. By the time the radio reporter signed off for the day, the Freedom Association for Individual Reform (FAIR) had begun.

As progressive-minded white kids in suburbia, they were distanced from movements closer to the city center, so they modeled FAIR after what little they knew about the larger student-run political organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), whose members organized thousands of acts of resistance across the country. There was no SDS chapter in Louisville, but they didn’t feel ready to step into leadership within a large organization. Inexperienced but eager, they were ready to define their own local movement.

At its start, FAIR was merely an informal gathering to discuss dress code regulations, politics, the Vietnam War, and anything else that was relevant.

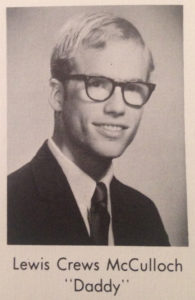

“Along with the big deal about the Vietnam War, it was about personal freedom of choice,” said Crews McCulloch, one of FAIR’s earliest members, describing what drew him and so many others into join.

FAIR’s first meetings were held in members’ basements or backyards, but as FAIR grew, basements and backyards soon became too small. Many members belonged to some of the more progressive churches in Louisville, so when there were finally too many members to squeeze into one person’s basement, they started meeting in Unitarian church youth groups spaces, such as the Thomas Jefferson Unitarian Church on Brownsboro Road.

Every few days after school, kids from Westport High School and a few from neighboring schools met in the carpeted church spaces to discuss issues they were facing in the community. It was around the time when more people were starting to show up to meetings that FAIR began semi-regularly printing a newspaper called County FAIR.

County FAIR included both member and reader contributions of poems, editorials, and other short writings in response to injustices in their schools, communities, and country. With radical themes and language, the publication was the students’ attempt to parallel the underground press movement that was expanding from progressive cities as a way to spread counterculture completely independent from mainstream media.

Publications such as the Los Angeles Free Press in California and the New England Free Press in Massachusetts were using print publication to voice their dissent for a variety of social issues ranging from the Vietnam War to different facets of the civil rights movement.

McCulloch, Conley, and Hansen had noted that movements were using “underground” or small press publications to spread their ideas, so the created their own – County FAIR. McCulloch recalled distributing copies along Bardstown Road and at schools like Seneca, Atherton, and Eastern to help FAIR reach beyond the walls of Westport.

Contributors to County FAIR fought for reform in a variety of areas, but one topic that came up again and again was school dress codes, which students constantly ridiculed.

Contributors to County FAIR fought for reform in a variety of areas, but one topic that came up again and again was school dress codes, which students constantly ridiculed.

“I find that not being clean-shaven is not degrading to my morals,” they wrote. “The administration has no more right to tell us how to dress than to tell us how to think.”

As much tension as there is surrounding modern dress codes, the average dress code from the 1960s was much more restrictive. Specific differences primarily included restrictions on hair length for males, makeup for females, and footwear. In most cases, boys’ hair had to be worn at or above the ears and “extreme or unusual haircuts” such as flat tops, ducktails, and long hair were forbidden according to a 2012 Smithsonian magazine article about high school dress codes in the 1960s. Dress shoes with black, navy, or white socks were a common requirement and females were permitted to wear makeup “only in moderation.” Some styles, such as pants for females and the use of hair dye, were strictly prohibited in most schools. As high school activists who identified with the period’s counter-culture movement, they found dress code conventions in contrast with what they felt comfortable wearing – trends that faculty and administration considered extreme or unusual.

“We were all labeled because of our dress or hair as either strange or weird or somebody to avoid,” McCulloch said of his peers and authority figures.

As the national anti-war political movement escalated, FAIR members recall that dress codes became more heavily enforced.

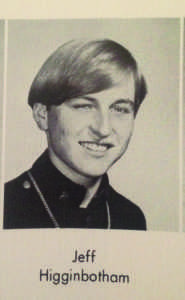

“I think they were using the dress code to target us,” said Jeff Higginbotham, a former Westport High School student who was a sophomore when Hansen and Conley were seniors.

McCulloch noticed similar situations. “If you were putting out a red flag, they would find a way to do something about it,” McCulloch said.

For that reason, Hansen decided to make a point to the administrators.

On a day later that fall, he walked nervously through the front doors of Westport High School. On his way to his locker, he saw that people who usually gave him no notice were turning and staring. Taking in their shock and surprise, Hansen smiled and walked more confidently.

Westport high schoolers Eric Hansen and Tom Conley sat on Conley’s porch on a fall day in Louisville, tired of endless school rules. Tired of being told to cut their hair to “traditional” lengths. Tired of the draft looming over their heads. Tired of not being able to do anything about it. They wanted to have a say in what was going on – and they knew they weren’t the only ones.

But it was 1968. They didn’t have cell phones or any way to communicate outside of face-to-face conversation and landline phone calls. They didn’t have Facebook to organize events or other social media for fast communication and planning.

Neither were speaking, but they were both thinking about the countless cases they’d seen of boys not being allowed to grow out their hair past their ears and girls not being allowed to wear pants, because both apparently served as too much of a distraction to the school environment. Just a few days ago they had seen someone expelled because of his hair.

The sounds of falling leaves and radio static filled the air as an all-too-familiar voice reported the daily updates on the Vietnam War. The death toll was growing higher and higher every day. All throughout high school they had sat silently through dress code issues, war crimes and injustices, and other situations that, to them, didn’t seem fair.

“We should have a group,” Hansen said, and he wasn’t talking about a radical organization of war protesters or even an active educational reform group – though both were similar to what FAIR would one day become. He was talking about a group of young men and women that would get together to discuss local, national, and global issues and propose steps towards progress.

Conley considered this for a moment and agreed. By the time the radio reporter signed off for the day, the Freedom Association for Individual Reform (FAIR) had begun.

As progressive-minded white kids in suburbia, they were distanced from movements closer to the city center, so they modeled FAIR after what little they knew about the larger student-run political organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), whose members organized thousands of acts of resistance across the country. There was no SDS chapter in Louisville, but they didn’t feel ready to step into leadership within a large organization. Inexperienced but eager, they were ready to define their own local movement.

At its start, FAIR w as merely an informal gathering to discuss dress code regulations, politics, the Vietnam War, and anything else that was relevant.

as merely an informal gathering to discuss dress code regulations, politics, the Vietnam War, and anything else that was relevant.

“Along with the big deal about the Vietnam War, it was about personal freedom of choice,” said Crews McCulloch, one of FAIR’s earliest members, describing what drew him and so many others into join.

FAIR’s first meetings were held in members’ basements or backyards, but as FAIR grew, basements and backyards soon became too small. Many members belonged to some of the more progressive churches in Louisville, so when there were finally too many members to squeeze into one person’s basement, they started meeting in Unitarian church youth groups spaces, such as the Thomas Jefferson Unitarian Church on Brownsboro Road.

Every few days after school, kids from Westport High School and a few from neighboring schools met in the carpeted church spaces to discuss issues they were facing in the community. It was around the time when more people were starting to show up to meetings that FAIR began semi-regularly printing a newspaper called County FAIR.

County FAIR included both member and reader contributions of poems, editorials, and other short writings in response to injustices in their schools, communities, and country. With radical themes and language, the publication was the students’ attempt to parallel the underground press movement that was expanding from progressive cities as a way to spread counterculture completely independent from mainstream media.

Publications such as the Los Angeles Free Press in California and the New England Free Press in Massachusetts were using print publication to voice their dissent for a variety of social issues ranging from the Vietnam War to different facets of the civil rights movement.

McCulloch, Conley, and Hansen had noted that movements were using “underground” or small press publications to spread their ideas, so the created their own – County FAIR. McCulloch recalled distributing copies along Bardstown Road and at schools like Seneca, Atherton, and Eastern to help FAIR reach beyond the walls of Westport.

Contributors to County FAIR fought for reform in a variety of areas, but one topic that came up again and again was school dress codes, which students constantly ridiculed.

“I find that not being clean-shaven is not degrading to my morals,” they wrote. “The administration has no more right to tell us how to dress than to tell us how to think.”

As much tension as there is surrounding modern dress codes, the average dress code from the 1960s was much more restrictive. Specific differences primarily included restrictions on hair length for males, makeup for females, and footwear. In most cases, boys’ hair had to be worn at or above the ears and “extreme or unusual haircuts” such as flat tops, ducktails, and long hair were forbidden according to a 2012 Smithsonian magazine article about high school dress codes in the 1960s. Dress shoes with black, navy, or white socks were a common requirement and females were permitted to wear makeup “only in moderation.” Some styles, such as pants for females and the use of hair dye, were strictly prohibited in most schools. As high school activists who identified with the period’s counter-culture movement, they found dress code conventions in contrast with what they felt comfortable wearing – trends that faculty and administration considered extreme or unusual.

“We were all labeled because of our dress or hair as either strange or weird or somebody to avoid,” McCulloch said of his peers and authority figures.

As the national anti-war political movement escalated, FAIR members recall that dress codes became more heavily enforced.

“I think they were using the dress code to target us,” said Jeff Higginbotham, a former Westport High School student who was a sophomore when Hansen and Conley were seniors.

McCulloch noticed similar situations. “If you were putting out a red flag, they would find a way to do something about it,” McCulloch said.

For that reason, Hansen decided to make a point to the administrators.

On a day later that fall, he walked nervously through the front doors of Westport High School. On his way to his locker, he saw that people who usually gave him no notice were turning and staring. Taking in their shock and surprise, Hansen smiled and walked more confidently. When he reached his locker, McCulloch, Conley, Higginbotham, and a few others were waiting there for him like usual. Their eyes grew wide and they laughed, skimming the top of his head with their hands, because in response to faculty complaints about the length of his hair, Hansen had completely shaved his head.

Teachers had been telling him to get his hair cut for weeks, but after they saw how short it was, Hansen received a one day suspension.

“It became a political statement rather than just a haircut,” Higginbotham said.

Hansen eventually grew his hair back to its original length. Like Hansen, though, the national demonstrations struck a chord with other teenagers who viewed dress codes as a point of contention.

“They felt that they should be able to have a say in their own education and how it was conducted which, coming from Catholic high school, was pretty novel,” said Larry Jouskey, one of Higginbotham’s friends from deSales High School who would sit in on FAIR meetings.

And in the absence of modern day communication technology, FAIR’s print publication was one of the few ways to spread ideas to youth throughout Louisville.

And in the absence of modern day communication technology, FAIR’s print publication was one of the few ways to spread ideas to youth throughout Louisville.

“I would say that there was one social media, and that was music,” Higginbotham said. “That was what was fomenting social unrest across ages and across the country.”

Bob Dylan, with his song “The Times They are a-Changin,” was widely considered an iconic initiator of music counterculture, followed by other artists and groups such as the Beatles and Pink Floyd. This new type of music spread a variety of controversial ideas about civil rights and the Vietnam War, and Louisville teenagers were not immune.

Throughout the city, high schoolers were coming into a new social and political consciousness. For many, FAIR was the perfect outlet.

The organization continued to grow in numbers until there were too many high schoolers to fit in the church youth group spaces. They needed to find a new meeting place quickly, so they chose Hogan’s Fountain Pavilion, a large gazebo in Cherokee Park that’s still used today for meetings and events.

In this new, outdoor meeting space, the group was able to further develop into something larger and more vocal. Their meetings were growing into full-fledged rallies, because one idea that FAIR members constantly reinforced in their publication was the importance of protests. They wrote that even when protests don’t seem to have an effect, “people have been made to listen, and that is the main objective.”

Now more than ever, students were standing up and demanding a voice in their education and vocally protesting the war.

On Jan. 25, 1969, St. Matthews Mall was full with the usual crowd of people coming in after work and school. Representatives from the U.S. Air Force took center stage with a display that no one could miss in an attempt to drum up support and recruit young men. They flashed smiles and handed out pamphlets, unaware of the three long-haired boys approaching.

Mall patrons avoided eye contact and the Air Force representatives looked on in shock as McCulloch, Hansen, and Higginbotham hastily set up their smaller counter-display. They were trying to convince the mall-goers that the war was senseless, or to at least provide a distraction from the Air Force’s display.

Most of the people walking by maintained a respectful distance from the contrast of the two, pulling curious children away from the scene, but some were more outspoken in their disagreement. The young men stood with false confidence as a large burly man walked up to them. He looked them in the eyes and spat on each of them from across the table.

“You’re just a bunch of un-American Communists,” the man said as his family looked on from a distance. “You need to get out of here.”

Rather than pack up and leave, the young men stood their ground, managing to recruit a few more students from around Louisville by the time they left.

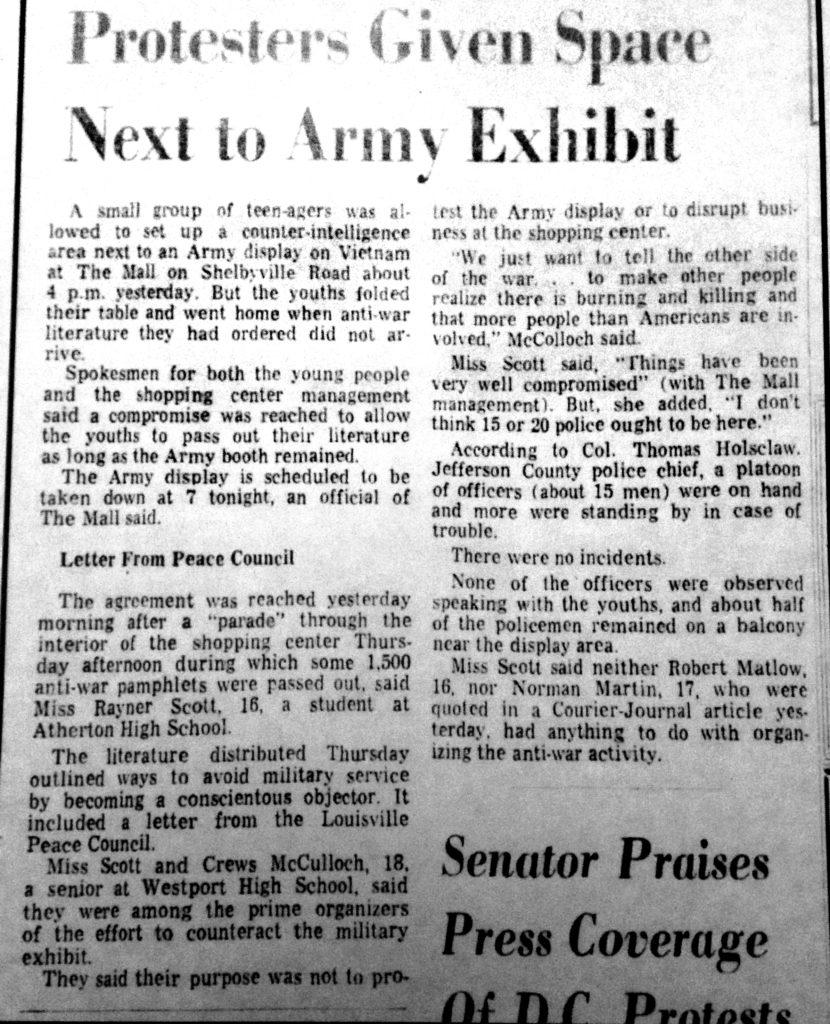

The next day, the boys were baffled when they saw an article in the Courier-Journal that read, “A small group of teenagers was allowed to set up a counter-intelligence area next to an Army display on Vietnam at The Mall on Shelbyville Road at 4 p.m. yesterday.”

The article described the protest, including a letter from the Louisville Peace Council about FAIR’s efforts to turn teenagers into conscientious objectors to the draft.

Higginbotham and the other members believe that the reporter’s incorrect usage of the term “counter-intelligence” to describe their group confused and alarmed people, planting doubt into the minds of parents.

“That newspaper article – to me, what I remember of it – was written in a way to tell parents to not let your kids come and be part of FAIR anymore, because of all the bad things involved,” Higginbotham said.

Some time that spring, protests became less frequent and people stopped showing up for rallies in the park. FAIR’s creators suspected that while the graduation of their seniors had some impact, the Courier-Journal article was the primary culprit of the group’s decline.

Furthermore, they believed their interactions with Carl and Anne Braden took a toll. The Bradens were well-known left-wing activists who had been charged with sedition in the 1950s when they purchased a house on behalf of a black family in an all-white neighborhood, a move to help desegregate Louisville housing. Carl Braden had lent them his mimeograph machine to print County FAIR, and FAIR’s members believed that general distrust for the Bradens was part of the reason the meetings stopped.

All over the country, underground newspapers and magazines were ending, yet spin-offs were beginning. It was in this way that underground press kept citizens motivated through politically rocky times. County FAIR operated on a much smaller scale, but it had a similar effect on students in Louisville. When FAIR ended, spin-off publications and groups began, and though they often didn’t get very far off the ground, they kept a spirit of activism alive in their members and in Louisville.

Time went on, and the friends graduated and said goodbye. Higginbotham, Hansen, and McCulloch continued protesting the war at their separate colleges; McCulloch was even thrown out of Morehead State University after reading anti-war literature at a school assembly.

“The auditorium was packed, and I basically just read an article from Newsweek magazine stating that the Vietnam War was unwinnable and we should get out,” McCulloch said. “About three hours later I was sitting in a room with the dean of students and the dean of men, and they basically gave me a week to get out of town.”

Now McCulloch is chair of the art department at Chatfield College where he uses his experience to encourage his own students.

Higginbotham, now researching social interactions with the University of Buffalo, used his experience from FAIR’s rallies to oppose the 1970 Kent State University shootings and various elections during college and graduate school.

Likewise, Hansen returned to his high school ideals with his participation in the 2011 protest movement, Occupy Wall Street, and in his work as a newspaper printer.

To this day, all three FAIR members keep informed on current issues. Now, they use social media and the reach of the internet to combat issues, using lessons learned as teens to influence others and take action against racism, sexism, and homophobia.

It’s not surprising that McCulloch offers this parting advice to teens grappling with issues of injustice.

“Don’t be silent if you feel something is wrong,” McCulloch said. “Speak out. That’s important.”

When he reached his locker, McCulloch, Conley, Higginbotham, and a few others were waiting there for him like usual. Their eyes grew wide and they laughed, skimming the top of his head with their hands, because in response to faculty complaints about the length of his hair, Hansen had completely shaved his head.

Teachers had been telling him to get his hair cut for weeks, but after they saw how short it was, Hansen received a one day suspension.

“It became a political statement rather than just a haircut,” Higginbotham said.

Hansen eventually grew his hair back to its original length. Like Hansen, though, the national demonstrations struck a chord with other teenagers who viewed dress codes as a point of contention.

“They felt that they should be able to have a say in their own education and how it was conducted which, coming from Catholic high school, was pretty novel,” said Larry Jouskey, one of Higginbotham’s friends from deSales High School who would sit in on FAIR meetings.

And in the absence of modern day communication technology, FAIR’s print publication was one of the few ways to spread ideas to youth throughout Louisville.

“I would say that there was one social media, and that was music,” Higginbotham said. “That was what was fomenting social unrest across ages and across the country.”

Bob Dylan, with his song “The Times They are a-Changin,” was widely considered an iconic initiator of music counterculture, followed by other artists and groups such as the Beatles and Pink Floyd. This new type of music spread a variety of controversial ideas about civil rights and the Vietnam War, and Louisville teenagers were not immune.

Throughout the city, high schoolers were coming into a new social and political consciousness. For many, FAIR was the perfect outlet.

The organization continued to grow in numbers until there were too many high schoolers to fit in the church youth group spaces. They needed to find a new meeting place quickly, so they chose Hogan’s Fountain Pavilion, a large gazebo in Cherokee Park that’s still used today for meetings and events.

In this new, outdoor meeting space, the group was able to further develop into something larger and more vocal. Their meetings were growing into full-fledged rallies, because one idea that FAIR members constantly reinforced in their publication was the importance of protests. They wrote that even when protests don’t seem to have an effect, “people have been made to listen, and that is the main objective.”

Now more than ever, students were standing up and demanding a voice in their education and vocally protesting the war.

On Jan. 25, 1969, St. Matthews Mall was full with the usual crowd of people coming in after work and school. Representatives from the U.S. Air Force took center stage with a display that no one could miss in an attempt to drum up support and recruit young men. They flashed smiles and handed out pamphlets, unaware of the three long-haired boys approaching.

Mall patrons avoided eye contact and the Air Force representatives looked on in shock as McCulloch, Hansen, and Higginbotham hastily set up their smaller counter-display. They were trying to convince the mall-goers that the war was senseless, or to at least provide a distraction from the Air Force’s display.

Most of the people walking by maintained a respectful distance from the contrast of the two, pulling curious children away from the scene, but some were more outspoken in their disagreement. The young men stood with false confidence as a large burly man walked up to them. He looked them in the eyes and spat on each of them from across the table.

“You’re just a bunch of un-American Communists,” the man said as his family looked on from a distance. “You need to get out of here.”

Rather than pack up and leave, the young men stood their ground, managing to recruit a few more students from around Louisville by the time they left.

The next day, the boys were baffled when they saw an article in the Courier-Journal that read, “A small group of teenagers was allowed to set up a counter-intelligence area next to an Army display on Vietnam at The Mall on Shelbyville Road at 4 p.m. yesterday.”

The article described the protest, including a letter from the Louisville Peace Council about FAIR’s efforts to turn teenagers into conscientious objectors to the draft.

Higginbotham and the other members believe that the reporter’s incorrect usage of the term “counter-intelligence” to describe their group confused and alarmed people, planting doubt into the minds of parents.

“That newspaper article – to me, what I remember of it – was written in a way to tell parents to not let your kids come and be part of FAIR anymore, because of all the bad things involved,” Higginbotham said.

Some time that spring, protests became less frequent and people stopped showing up for rallies in the park. FAIR’s creators suspected that while the graduation of their seniors had some impact, the Courier-Journal article was the primary culprit of the group’s decline.

Furthermore, they believed their interactions with Carl and Anne Braden took a toll. The Bradens were well-known left-wing activists who had been charged with sedition in the 1950s when they purchased a house on behalf of a black family in an all-white neighborhood, a move to help desegregate Louisville housing. Carl Braden had lent them his mimeograph machine to print County FAIR, and FAIR’s members believed that general distrust for the Bradens was part of the reason the meetings stopped.

All over the country, underground newspapers and magazines were ending, yet spin-offs were beginning. It was in this way that underground press kept citizens motivated through politically rocky times. County FAIR operated on a much smaller scale, but it had a similar effect on students in Louisville. When FAIR ended, spin-off publications and groups began, and though they often didn’t get very far off the ground, they kept a spirit of activism alive in their members and in Louisville.

Time went on, and the friends graduated and said goodbye. Higginbotham, Hansen, and McCulloch continued protesting the war at their separate colleges; McCulloch was even thrown out of Morehead State University after reading anti-war literature at a school assembly.

“The auditorium was packed, and I basically just read an article from Newsweek magazine stating that the Vietnam War was unwinnable and we should get out,” McCulloch said. “About three hours later I was sitting in a room with the dean of students and the dean of men, and they basically gave me a week to get out of town.”

Now McCulloch is chair of the art department at Chatfield College where he uses his experience to encourage his own students.

Higginbotham, now researching social interactions with the University of Buffalo, used his experience from FAIR’s rallies to oppose the 1970 Kent State University shootings and various elections during college and graduate school.

Likewise, Hansen returned to his high school ideals with his participation in the 2011 protest movement, Occupy Wall Street, and in his work as a newspaper printer.

To this day, all three FAIR members keep informed on current issues. Now, they use social media and the reach of the internet to combat issues, using lessons learned as teens to influence others and take action against racism, sexism, and homophobia.

It’s not surprising that McCulloch offers this parting advice to teens grappling with issues of injustice.

“Don’t be silent if you feel something is wrong,” McCulloch said. “Speak out. That’s important.” •