I got on the Transit Authority of River City (TARC) bus at the corner of White Blossom Boulevard and Springhurst with only a $1.75 and nowhere to go. You can’t walk down a street in Louisville without seeing a TARC pass by; nevertheless, this was my first time experiencing our city’s public bus system. I paid my fare, noted the student discount I could get next time, and shuffled to an open seat in the middle of the vehicle.

The drive was unremarkable. Passengers came and went, all lost in the sound of their headphones and the green blur of trees as the bus passed them by. The cycle continued as, once again, the bus pulled to a stop.

This time the clatter of a plastic bottle interrupted the routine.

“Damnit!” said a woman, an overflowing bag of manilla folders slipping out of her arms.

She considered her options, looking between the drink on the floor and the open bus doors.

“Ma’am,” the driver said. She appeared to be in her 40’s and had a sweet country twang. “You dropped your pop ova’ here,” she said, pointing to the lime green bottle sloshing at her feet.

“My God,” the woman huffed as she left the bottle behind and took a conscious step towards the exit. “Can’t you see my hands are clearly full?” she said. “You can pick it up.”

The bus driver remained composed, retrieved the bottle, and continued to drive.

Her professionalism and poise hinted to me that this was not the first time she had been left to clean up a rider’s mess. This left me wondering; who is this person when she leaves the bus? Who is this person when she is not picking up a woman’s garbage, or begging riders to pay their fare, or doing a thankless job with a smile on her face?

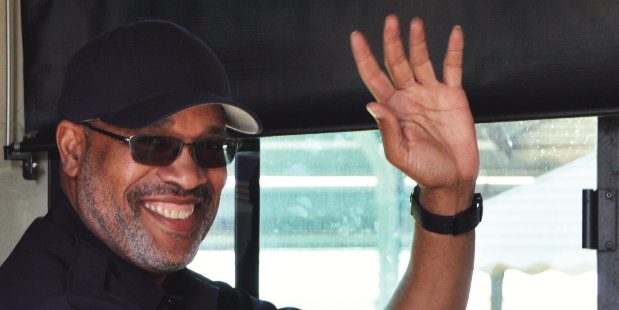

Later, I was reminded of this incident at Louisville’s historic Union Station when I sat down to talk with TARC bus driver Quintin Webster.

“Well, yes, riders are rude on the bus all the time,” he said. “So, what do I do? I just smile.”

As we walked around what used to be the city’s railroad hub, now TARC headquarters, I found that not only is a friendly grin a big part of who Webster is, but also one of his responsibilities as a public service worker.

For the past six years, Webster has been a coach driver for TARC. Webster picks up routes throughout the city, meeting people from “all walks of life. From the good, the bad, and even the ugly,” he said with a wink, leading us out of the historic building and towards the parked buses.

Webster’s face lit up as he discussed his work, often interrupting stories with a bubbly, “I love drivin’ the bus.”

However, as much as he enjoys his job now, getting himself to where he is today was anything but easy.

“I’ve worked a lot of jobs to keep food on the table,” Webster said. “I was a driver for TARC 22 years ago, but got laid off after two years and put into an unemployment program that helped me get a degree. Then I worked for IBM — but again got laid off.”

As we continued to walk the perimeter of the parking lot, Webster revealed that his struggles with unemployment were the least of his worries. Twenty-one years ago, Webster lost his 15-year-old son, Quintin Hammond, when two men attempting to rob Quintin of his shoes shot him instead. Quintin was on his way to the school I have called my own for four years now — duPont Manual High School.

Webster’s son was known at Manual for his enthusiasm and well-rounded personality, which I could clearly see he got from his dad. Hammond’s murder not only shook the school community, but left a mark on Webster that lies hidden behind his charisma.

“Of course that was the worst day of my life,” Webster said, “but I am still here and I am still standing. It is only by God’s grace and mercy that I’m still going.”

We headed towards the back parking lot as I allowed silence to fall over us for the first time in the interview. I was reflecting, and I think he was too. Hammonds death has impacted not only his father, but the teachers I see everyday, even his football coach, who I now call Principal Mayes. I was shocked by the connection that perfectly summed up my reason for writing this piece and startled by the realization of every time that I — and many of you — had overlooked the person behind the job.

“Every driver’s got a story. You’re just hearing mine, but other riders don’t know. Some of them treat us like we have no story, even though I always try to be kind and professional,” Webster said.

He walked us back towards Union Station as the interview drew to a close. I shook his hand, thanking the college graduate, the father, the driver, the man behind the thankless job.

As a bus rider, a student, and a Louisville teen it is crucial to treat those who provide us with a service as people. Every driver, every person, has a story and now I’ve heard Webster’s. I still don’t know that woman who drove me last week, but I don’t need to hear her story to know that she has one. «