Lost In Translation

The move to the States can be challenging, but finding out how to fit into American culture can be even more difficult.

Immigrant parents come to Kentucky carrying the weight of their luggage along with the traditions and beliefs of their home country. They’re faced with the challenge of maintaining their culture despite added pressure to adapt to and learn about American norms, and their children must also find middle ground between their parents’ culture and American society.

For the kids, every day carries new decisions: blue jeans or traditional clothes? A dish from their home country or a cheeseburger from the drive-thru? Though these choices may seem small, they can represent the changes in identity that come as soon as they cross the border.

“Assimilation is working your way into that cultural frame of reference in such a way that you know the cultural cues, the nuances of a culture,” Frank Hutchins, an associate professor in anthropology at Bellarmine University, said in an interview with On the Record.

Hutchins described a struggle between “Americanizing” and holding onto heritage: children usually try to act the same way that their peers do, while parents tend to stick with what they know, creating a disconnect between parent and child.

On paper, this rift may seem just like political jargon and complicated terms, but for the families that experience it first hand, it can be a huge burden and cause perpetual confusion about one’s identity.

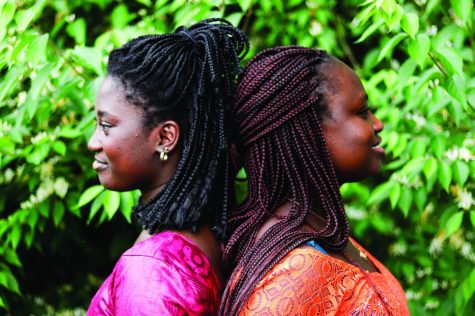

Fatima (left) stands back-to-back with her mother Jainaba (right) in their backyard. Photo by Sylvia Cassidy.

Fatima

Sitting at her kitchen table, Fatima Gaye, a 16-year-old sophomore at Atherton High School, discussed her plans for the night with her mother, Jainaba. Fatima wanted to spend the night with her friends, but her mother had some objections.

“That doesn’t make any sense to me,” Jainaba said.

For Jainaba and her Gambian background, sleepovers were anything but usual. When Jainaba was growing up in her home West African country, The Gambia, she was never allowed to spend the night away from home. But this debate had come up in the Gaye household more than once. Nonetheless, Jainaba gave Fatima permission to spend the night under another roof.

Jainaba doesn’t want Fatima to be “the kid with strict parents,” but for parents raising a child in a culture they are unfamiliar with, figuring out what to hold on to and what to forbid is tricky, especially while trying to uphold the values of their traditions.

“It’s a little hard when you have a child here, and you have that background in Africa — the way you were raised,” Jainaba said. “And then you are in America and you want to bring them up in

this culture.”

Jainaba has taken Fatima to The Gambia a few times, with the most recent trip in 2015. There, Fatima was faced with different customs — she said that she was rarely on her phone and less focused on what people thought of her. People in the streets were constantly making casual conversation, rather than walking past with their eyes on the ground.

“When you’re over there, you don’t even care about all that stuff,” Fatima said. “It was eye-opening.”

Fatima was caught off guard by how close-knit her mother’s hometown was.

“Everyone knows each other,” Jainaba said.

Fatima enjoys the social environment in The Gambia and tries to incorporate the same type of community support into her daily life when she comes back home. She tries to talk to everyone she meets and get to know them a little, like the people in The Gambia do.

Although the difference in hometowns causes some arguments about what is “normal” in the Gaye household, the two have connected over the root they share in The Gambia. Since the discussion that they shared, Fatima has been able to spend the night elsewhere with her friends.

Kassie Padron

and her mom, Rosa Rivera, share a laugh outside of their kitchen. Photo by Sylvia Cassidy.

Kassie

Kassie Padron, a 15-year-old sophomore at Fern Creek High School, celebrated her quinceañera in July. A quinceañera is a traditional Latina celebration that marks a girl’s passage into womanhood — and Padron wanted hers to be perfect.

But the day of, the makeup artist canceled last minute, the limo company changed the reservation, and the thick air and dense humidity formed one of the biggest thunderstorms of the summer.

Despite the series of setbacks, no-shows, and changes of plans, Padron still described this kindred day as “spectacular.”

“It connected me back to some of my roots,” Padron said — although she still doesn’t feel a full connection.

Her parents are from Mexico, making her a second-generation American. Padron explained the difficulty of connecting with her Mexican heritage and simultaneously feeling part of American culture.

“It’s kinda feeling like you have one foot in one place and another in the other,” Padron said. “It’s weird because you feel like you’re too American to be with your family and you’re too Mexican to be around other people because you have this different view and culture.”

This gap is illustrated in nearly every aspect of Padron’s life, down to the way she communicates in her home. Her mother, Rosa Rivera, almost exclusively speaks Spanish, which she taught to Padron and her sister.

Because of this, she developed an accent when speaking in English that made her heritage easily identifiable among her peers — even though she just wanted to fit in.

In response, Padron made an effort to hide her accent. She watched American movies and television shows, mainly Disney and Barney, in order to pick up the slang. As time progressed, her accent became undetectable.

“I seem pretty American,” Padron said. “It’s not like most people assume that I’m Mexican.”

In addition to suppressing her accent, Padron wouldn’t talk about her Catholic faith or eat spicy foods because she thought embracing those traditions would make her even more of an outcast, especially around non-Hispanic white people.

“I know it’s weird because even some white people like spicy foods,” Padron said. “But it was just a subconscious thing.”

Catholic figurines line the mantle in the Padron family household. Photo by Mattie Townson.

Padron felt her culture was slipping away from her as she tried to fully submerge herself in American culture. But as her quinceañera quickly approached, she made a deliberate effort to connect back to her roots — starting with her parents.

Her relationship with her parents was already strong,

but she worked to strengthen

it further by familiarizing

herself with their values, beliefs, and religion.

A framed photo of Kassie taken in elementary school is adorned by symbols of religion and family. Photo by Mattie Townson.

“My parents taught me to be respectful and cordial with other people,” Rivera said through translation. “They also taught me to actually listen to what people have to say.”

Padron works hard to apply these principles in her everyday life.

“I’ve seen the effects of bigotry in this country and I try not to add to that negativity in the world,” Padron said. “I just try my best to be nicer to people and not hold those same stereotypes to other people that have been held against us and other people.”

So, when the day of her quinceañera finally arrived, it felt like a triumph for Padron to intimately relate to her heritage.

“Bringing that tradition back into my life was really important to me because it did connect me back to my grandmother,”

Padron said. •

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.