1 IN 5

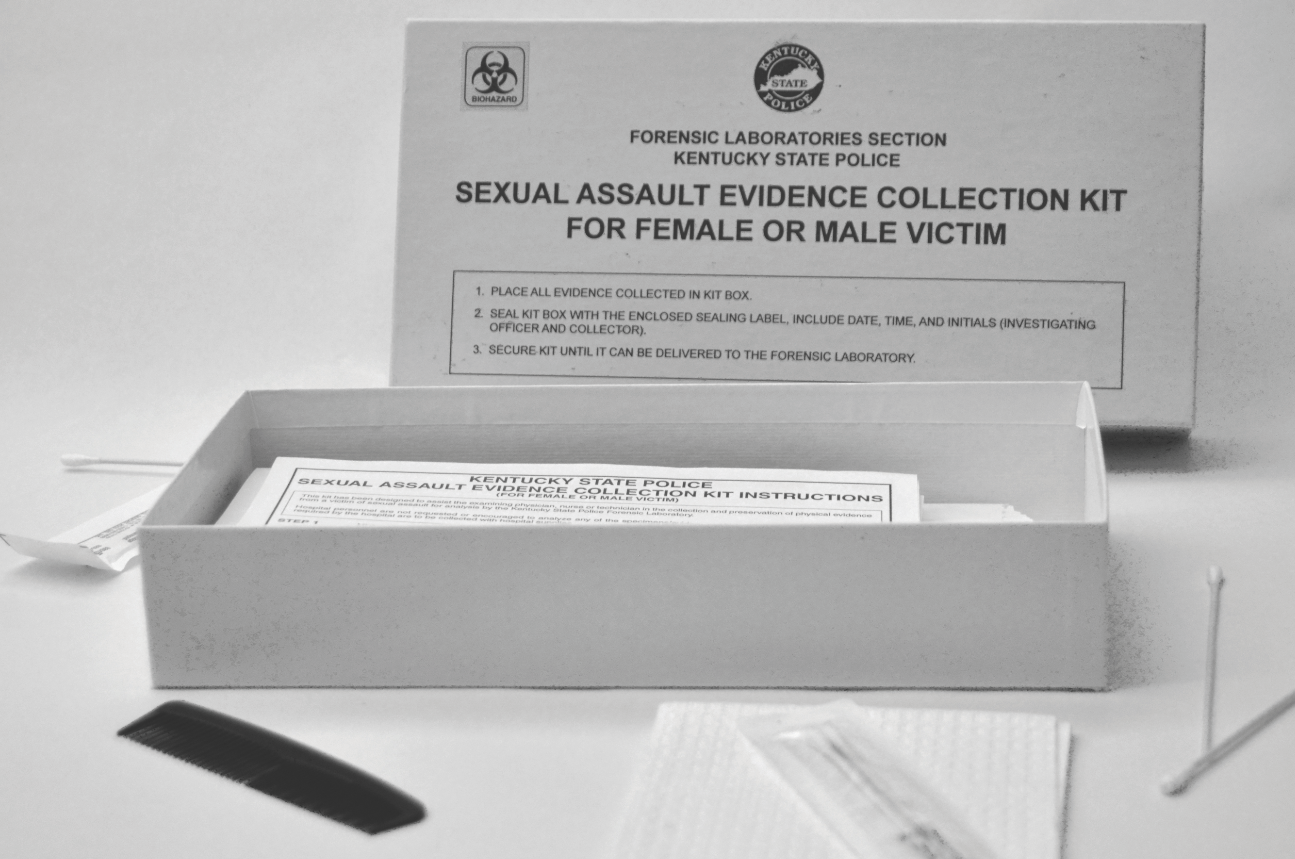

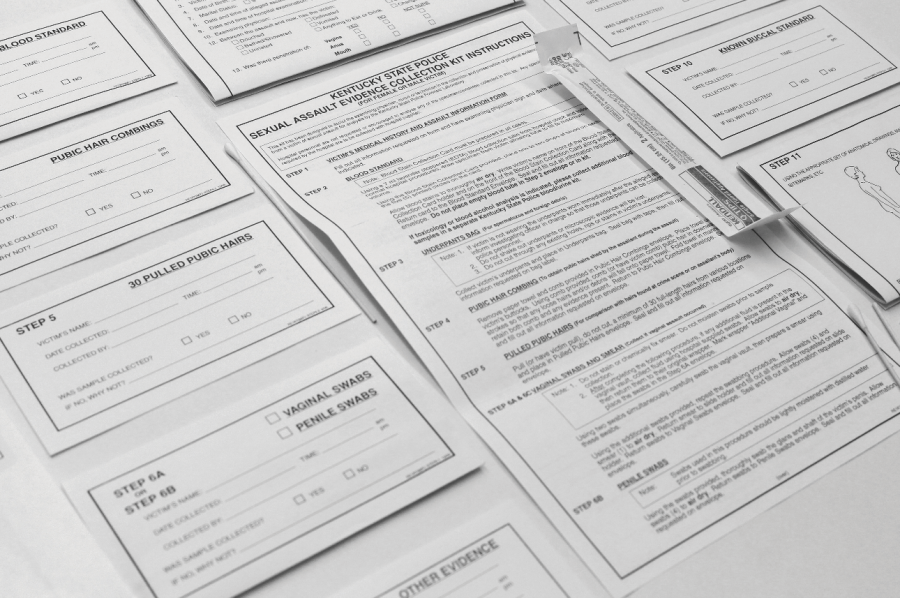

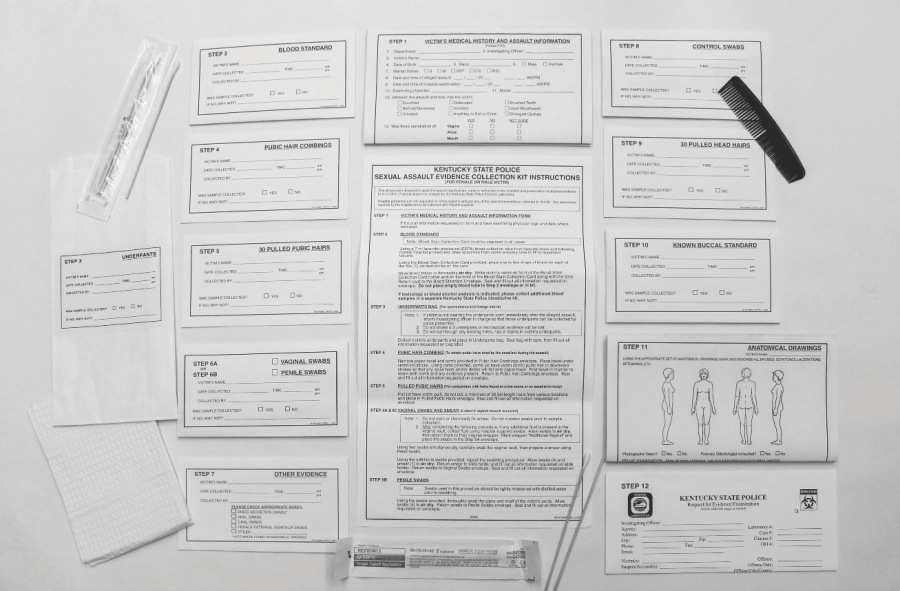

RAPE KIT • This is an evidence collection kit, or rape kit. Cotton swabs, combs, and pads can all be seen beside it. Photo Credit: LAINEY HOLLAND

They step into the Center of Women and Families (CWF) in a detached state of shock, in tears, or in an effort to behave as normally as they know how. They might miss class because they couldn’t stand to walk across the street and see their perpetrator. While their peers decide whether to study for their math final, they are deciding whether or not to testify against their assaulter in court.

These are the kinds of situations Amy Turner, the Director for Sexual Assault Services at the CWF, describes dealing with every day. They are the experiences of Olympic gymnasts, up and coming vocal artists, and maybe even the woman that lives next door. It was a fleeting moment in their youth that altered the course of the rest of their lives — they are victims of alleged sexual assault.

These women aren’t anomalies within our current youth population. According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), females ages 16-19 are four times are four times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape. Teenage girls are at the forefront of this issue, and it’s a difficult issue to conquer.

An assault occurs every 98 seconds in the U.S. according to RAINN; sexual assault is almost commonplace in our society. It has caused perpetrators of the women listed above — like Larry Nassar, USA Gymnastics national team doctor and child molester —to stand against women’s accusations and behind a podium in court. Even President Trump has been accused of sexual harassment and assault, telling television personality Billy Bush to “grab em’ by the pussy” on the set of “Days of Our Lives.”

With rape being the most underreported crime according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, women have begun to create an environment of empowerment and bravery that encourages victims to step from the shadows and declare, “me too.”

“The movement gives people the ability to see that they are fighting for themselves and they are fighting for other women,” said Jenny Kuerzi, Crisis Counselor at the CWF in an interview with OTR.

Despite this surge of motivation pushing women to come forward with stories of sexual assault, there is a knowledge gap regarding what this can entail. Putting a perpetrator behind bars is an arduous and potentially re-victimizing experience. It may force a victim to have to recount the painful memories of their sexual assault. A trial can consist of the collection of concrete evidence which comes from a rape kit, although that’s not the route that all women choose to take.

What is a rape kit?

A rape kit is a package used by Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE) to preserve physical evidence following an alleged sexual assault. Inside are directions, a comb, bags, paper sheets, swabs, envelopes, documentation forms, and other materials used for DNA samples.

Just because a victim gets a rape kit processed does not mean there will be a match to a perpetrator’s DNA in the criminal database, although the rape still could have occurred.

A woman can get a rape kit at no cost for any instance pertaining to sexual assault. Despite the name, rape kits could be useful in any of the crimes that fall under the umbrella term of sexual assault.defines sexual assault as harassment, touching without consent, and penetration without consent. However, rape kits are more commonly used in rape cases because that’s where evidence collection becomes most necessary.

It is come forward with their rape with their rape and get a rape kit tested immediately, if at all. According to RAINN, three out of four cases of sexual assault go unreported. When a person chooses not to get a rape kit, there is still hope in finding bits of evidence, but the best chance for a prosecution is for a woman to report and get tested right away.

The rape kit process

A victim of sexual assault can choose to either go to the police or a hospital, and the procedure is a little different for each of these places. A SANE will come in and obtain a thorough medical history. The victim stands on a large sheet of paper while undressing in order to catch any hair or fiber that may fall from his or her body — they can’t risk losing any possible evidence.

“The thing that is really important to me is choice. Throughout this entire process, the choice to be able to decline it or go through with it needs to be their decision,” Kuerzi said.

Nurses do their best to make sure their patient is informed and comfortable, but in this situation, it’s difficult to keep the process from being invasive. The victim’s

clothing and the sheet are collected for testing of hair, fibers, and any additional evidence.

Depending on the victims recollection of the assault, they can choose what parts of the examination they would like to participate in. These options include: urine, blood, and semen samples; swabbing the mouth, vagina, and anus; combing through and sampling body hair; scraping under the fingernails for remnants of skin cells if the victim tried to fight back. When there is physical evidence of violence, the nurse can photograph those bruises, bumps, and scratches for documentation.

For some, the rape kit process brings a sense of alleviation and care, but for others, it can be a distressing repetition of the vulnerability felt by the victim during the sexual assault.

What if it happens to me?

In the event that you are sexually assaulted and want to get tested, there are a couple of things crisis counselors advise you to refrain from doing. Victims should not change clothes or shower, even though it may be your first instinct. Eating and going to the bathroom also may tamper with evidence that could be necessary in a court case, but it’s for you to decide. Counselors and nurses understand that it can be difficult for women to steer away from doing the things that may provide comfort in this moment of consternation.

At the CWF, a SANE will conduct a rape kit examination. All hospitals are required to have SANE on site, but UofL is the only hospital in Louisville that has them available all 24 hours. If you have a rape-related health issue that may put you in immediate danger, you lose the choice in whether or not you want to do the kit. The hospital must admit and test you.

Whether or not you’re sure you have been raped or sexually assaulted, you can still call the CWF or have a rape kit tested within 96 hours of the assault. It is important that you trust what your body is telling you; the sense of discomfort and fear that someone may be struggling with after a sexual assault may be their best source of affirmation.

If you are one in five women who are sexually assaulted in their lifetime, please don’t hesitate to call the crisis hotline at 1-(844)-237-2331.

Many women aren’t prepared for the possibility that it could happen to them. It certainly wasn’t something Bonnie Levitt, 25 at the time, was expecting when she was raped by Shawnee High School graduate and former Kentucky basketball player, Tom Payne, who was convicted for five rapes and four attempted rapes. He attacked Levitt in the garage of her California home on Feb. 14, 1986.

During the rape, Payne covered her head with a towel and hoisted her onto the roof of her car. However, Levitt told us in an interview that she wasn’t willing to go down without a fight. Refusing to let police show up on her mother’s doorstep on Valentine’s Day with news that her daughter had been killed, Levitt took the brooch from her jacket and began stabbing Payne in the head.

Police walked in on the scene of the crime relieving Levitt of what had become a fight for her life, and she was taken to the hospital where she went through the rape kit process.

“They looked at all of my bruises and scratches on my body and they took pictures of me from head-to-toe. They also swabbed my vagina, combed through my pubic hair and head hair. After that, they swabbed my mouth because he tried to kiss me,” Levitt said, “But I don’t ever remember feeling uncomfortable.”

Although the rape itself was mentally and physically scarring, she said it was the long and grueling road that came after that was the most painful.

Taking the stand

It took almost an entire year before Levitt got the chance to testify against Payne in court. Once there, Payne lied about what really happened. According to him, Levitt was a prostitute who agreed to have sex with him for 35 dollars. He claimed her accusations of rape were racially motivated, considering she was white and he was black.

Levitt rehearsed her story with her lawyer over and over again. Yet as soon as she stood behind the podium, she felt as though every detail of this traumatizing experience would somehow be turned into the wrong answer. She described it as re-victimizing.

But pointing at Payne and saying “yes, that is the man who raped me” restored the power in her that Tom Payne had taken away a year prior.

Having the evidence that was collected through the rape kit process gave Levitt the proof to back her story, and together, it was enough to prove Payne guilty. He was sent to prison once again, having been released just three years before after serving ten years for separate rape charges.

This isn’t always how the story ends, though. According to Turner, Kentucky has a 3% conviction rate for rape cases. But the extent to which a woman feels like she’s achieved justice isn’t always determined by whether or not their perpetrator serves time. In several of Turner’s cases, the victim knew of various other people in their position who didn’t feel comfortable going forward alone.

“Now, they feel like they can band together and go after this person. It creates community and camaraderie,” Turner said, “I think even if the person doesn’t see jail, they at least stood up to that person. Sometimes that’s just enough.”

What are my rights?

Rape kits are not exclusively for adults. Minors 13 or younger must go to a children’s hospital, such as Kosair Hospital in Louisville, where nurses are available who specialize in younger kids. Those ages 14 and 15 can get tested at both the CWF and UofL Hospital if accompanied by a parent or guardian. According to Kuerzi, minors 16 and older, however, may get tested without notifying a parent as long as they have received permission from someone 18 or older whom they trust.

Regardless of age, once a victim begins the rape kit process, they are not obligated to follow through with each aspect of it. A nurse will inform the victim about each step and they can decide which parts of it they would like to undergo.

Victims, like Levitt, who get a rape kit tested, also have the right to free contraceptives at the clinic. They will be provided with both Plan B and a free sexually transmitted disease scanning.

“After all of this they gave me a handful of pills. I don’t know what they were but they were just for everything. They even gave me the ‘morning after pill,’” Levitt said.

One of the pills she was given was a two-dose 12-hour contraceptive. After a strenuous 24 hours of playing back the rape in her head and for police officers, she went home and slept through the second dose. Consequently, Payne left a lasting mark on her body that would make moving forward even more difficult. Months later, Levitt miscarried having never even realized she was pregnant.

It’s her choice

There are many different factors that contribute to a victim’s decision not to report. According to Kuerzi, these include past negative experiences with law enforcement or hospitals and pushback from family and religious affiliations. She stated another contributor is the sexist platform in which society perceives victims. For example, some of the public deemed Christine Blasey Ford to be a liar because of her sexual assault allegations against Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh. The multiple death threats she received for coming forward highlights why some women don’t speak up in fear of retaliation, backlash, and harassment. But in the end, it comes down to the internal struggle that victims are faced with. The choice between moving past an experience like this and fighting to put an attacker behind bars is not an easy one.

“I think people struggle with, ‘am I gonna do all this work, am I gonna talk about what happened to me over and over again for that person to not even go to jail or to go to jail for like six months.’ To them it doesn’t feel worth it,” Kuerzi said.

This was the mindset of one college student, now 22, when she was sexually assaulted by her brother-in-law at just 13 years old. For this story, we’ll call her Samantha to protect the identity of herself and her family. Because of the close relationship she shared with her perpetrator and the fact that they were both drunk when it happened, she couldn’t help but try to justify his actions. Just entering her teenage years, Samantha wasn’t aware that rape kits were an option, and decided it’d be easier to remain silent. For months, she couldn’t bring herself to tell her mother or her sister, the woman that went home with Samantha’s assaulter every night.

“I didn’t really want him to go to jail,” said Samantha. “I loved him.”

To this day, Samantha still has flashbacks of what happened to her. Although she never got the chance to put her perpetrator behind bars, she says she would tell a woman that was in a similar position to get a rape kit done the day after if they really want to prosecute. The actions you make immediately after have the ability to affect you and your healing process for a prolonged period of time. Samantha said she would tell victims to “think long and hard about this decision.”

The backlog

In addition to the grueling internal conflict women are faced with, in some states, they are met with an external setback — the backlog. For years, our country has grappled with an accumulation of rape kits in the system that go untested. Although rape kits don’t always match women with a definite perpetrator’s DNA, due to the backlog, they are forced to wait months or even years for any

kind of result, making justice even more difficult to obtain.

Kentucky was among the backlogged states, sitting on 3,090 untested rape kits in 2015. Now in 2019, that number is down to zero. In April 2016, Kentucky passed the SAFE Act in an effort to combat the backlog issue. It requires that hospitals notify law enforcement 24 hours after completing any rape kit. Then, police have five days to retrieve the kit and 30 days to submit it to the lab for testing. As of 2018, the lab must have kits tested within 90 days, but in 2020, they hope to reduce that number to 60. Additionally, Kentucky is working on becoming the first state to put rapid DNA testing into action. This means rape suspects could be identified within hours.

Kentucky serves as an example of a state which has made a positive effort to decrease untested rape kit numbers significantly. States like North Carolina, California and Florida still have over 13,000 untested rape kits. As a state, we’re overcoming this issue, but as a country, we still have work to do.

Believe them

Levitt says her decision to come forward with her rape was undoubtedly the right one. It gave her story an ending, and it gave her closure. Levitt, now a woman in her late 50’s, spends her spare time painting with her friends in her Hollywood home.

Payne is on parole after spending over 30 years of his life in prison, and she says little hate for him remains in her heart.

“At this point all I can say is ‘have a great life, I hope everything works out for you, and you’re 68 years old so don’t waste it,’” Levitt said.

Her bravery behind the stand put Payne behind bars. This is only possible if we believe victims. Turner believes a culture where it’s the victim’s job is to prove they tried to prevent what happened is one that needs to change.

“We are conditioned as people to believe the perpetrator more than we are to believe the person who has experienced the assault,” Turner said.

The reformed society she envisions is one where we don’t argue with victims, where we don’t refrain from coming forward in fear of “ruining a young boy’s life,” where we don’t try to validate sexual assault by saying “boys will be boys.” It’s about refusing to dismiss the abusive and irresponsible behavior of men and being insistent that we recognize how their actions affect people. Until we start consistently having these conversations, Turner believes her job will continue to exist.

“If we just take the politics out of it and talk about people as human beings, then maybe we can get to a place where there are healthier conversations. Will that happen in my lifetime?” Turner said. “I’m kind of counting on you all.” •

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.