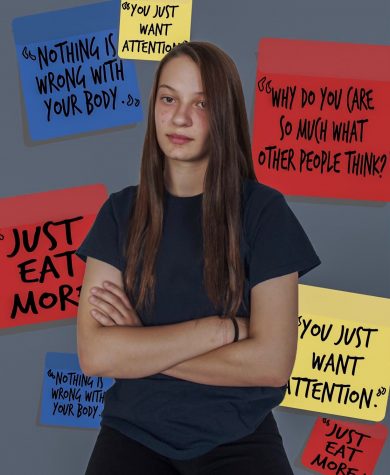

Defining My Disorder

My eating disorder is a complicated story, but that doesn’t mean we can just ignore it.

Disclaimer: This story mentions eating disorders and certain things that trigger them.

My mom bugs me about my diet sometimes, but I’m just like everyone else I know. So I haven’t really thought about this appointment, because it’s no big deal. But as my mom and I pull into the parking lot enclosed by uniform buildings, my anxiety intensifies and my mind is clouded with the fear of what will happen next. What are they going to say or make me do?

My skin is painted in goosebumps as I walk into the impersonal lobby. Everything is in place and clean. It makes me feel like the people there aren’t human enough, like they fit into a box of societal constructs. That makes me nervous because they could judge me, or not understand the parts of me that aren’t ‘perfect.’

I turn right and I’m greeted by a woman behind a counter with a sliding-glass window. My mom checks me in and I wait in the lobby for a few minutes. They have a jar of chocolates sitting on a table, which I find ironic because of the office I’m in. My therapist is ready for me. As I walk through the hall to her room, I notice that each room seems to have its own personality, which is comforting. It reminds me that these are real people with real lives, not just people going through the motions in a very clean and proper office building. I’ve only met my therapist once before — the time when I poured out my entire life and all my problems to her.

I always find it tiring, going through the same routine when I see a new doctor. When I first meet with pediatricians, psychiatrists, and each new therapist and specialist, they tell me the confidentiality spiel about how everything we talk about stays between us unless I’m putting myself or others in harm’s way. Next, they ask me what’s going on — why I’m sitting there across from them in need of their help.

So on this day, I sit on the white leather couch that has a pink blanket draped over it. She sits in her chair across from me. She’s holding a clipboard that has a list of things to talk about, things she’s assessed based on everything I told her last time. She speaks in a serious tone, as to prepare me for the life-altering news she’s about to give me. She briefly summarizes my characteristics and the fact that I need treatment before she says it:

“You have atypical anorexia nervosa.”

That is not at all what I was expecting.

The dictionary definition of an eating disorder is any range of physiological disorders characterized by abnormal or disturbed eating habits. According to the American Psychiatrist Association, there are three main types of eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Some of the most prevalent characteristics associated with eating disorders are binging (eating unusually large amounts of food at once) and purging, which can include eating small meals, self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise, and laxative or diuretic abuse. People with these eating disorders tend to be very critical and obsessive about their weight and body shape.

I didn’t think I acted like someone with an eating disorder. Sure, I didn’t eat a ton all the time but it was just because I wasn’t that hungry. My eating disorder, anorexia, appears in ways specific to me and my body. For me, eating in front of people is a problem. Everyone around me could be eating but it would still be so hard for me to do it with them. It’s too loud, chaotic, and out in the open. So I still ate, just privately. In my mind, it was simply a matter of personal preference.

In reality, it wasn’t just a preference. Not eating when I was in a rush, around too many people, or just because I didn’t “feel like it,” was not just some preference. I couldn’t. I didn’t ever tell myself not to, but my eating disorder is sneaky in that way.

I don’t look like a person that’s anorexic either. I want you to picture a person with an eating disorder. What comes to mind? In my head, being anorexic means my bones are showing through my skin, my hair is frail, and I look sickly. The extent of my knowledge of eating disorders at that point was based on stereotypes and extreme cases I had heard of. But in reality, I don’t look like that. So, as it turns out, you can have an eating disorder and look totally “normal.”

According to a study by the Oregon Research Institute, as much as 13% of youth may experience at least one eating disorder by age 20. Furthermore, eating disorders are most prevalent in adolescent girls. Yet, most people don’t know someone with one. Or at least they think they don’t.

In the time I’ve spent in the waiting room before going to talk to my therapist, I’ve seen multiple people I recognize. There were people I went to school with or played volleyball with, and I never would have guessed they would be there. I thought I didn’t know anybody with an eating disorder, but I realized I was far from alone in my struggles.

Even though it seemed like eating disorders were less rare than I previously thought, I still have never heard a conversation about them. Which, to a degree, is understandable. They’re scary. When I was diagnosed, I didn’t tell many people, because my first priority was to figure out my process for recovering and stabilizing.

However, once I got my footing and felt I was in a place where I could speak about my eating disorder, I did. I’m open about what I’ve gone through because it’s important to me for people to know and understand what anorexia is and how it affects a person. With a greater understanding, maybe someone can recognize the signs in themselves or feel more open about talking about their struggles, or just realize it’s not something only they experience. The smallest amount of support means the world to someone struggling with an eating disorder. After all, the whole basis of the illness is extreme self-consciousness because you feel the need to look and be a certain way.

“Why don’t you just eat more?” people often ask. It’s a logical question, I don’t know how you would possibly know how it feels to just not be able to put food in your mouth and swallow until you can’t. I never made a conscious decision to eat a significantly smaller amount so I could lose weight. Societal pressure built up, and somewhere along the line I started conforming to it, or trying to at least. In the developing stages of my eating disorder, I stressed a lot about what I ate and eventually decided to stop worrying about it so much and just try and eat balanced and listen to my body. That slowly turned into not eating much at all.

The longer I ate less and less, my body took the cue and stopped reminding me when I was hungry. At this point, I wasn’t eating much anymore but my body wasn’t trying to tell me to either. I know you have to have a certain amount of nutrients to function, but the idea of eating made me nauseous, or I didn’t like the food available, or there were too many people around, or a range of other things. I would wait so long without eating that I would feel sick, which then made me want to eat less.

Talking to people about my eating disorder and specifically being around them when I ate encouraged me, even if they couldn’t sympathize with my exact situation. The more I talk about it, the more I learn that other people experience the same things as me. There have been times when I’ve told others about my issue and later someone would come up to me privately and tell me they struggle with the same things. It’s totally okay and normal for people not to be as open about their eating struggles as I am, but they may feel more comfortable talking about it if they felt they had a community that they knew could support them.

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.

Cris Wolf Harper • Oct 22, 2019 at 5:41 pm

I’m so proud of you Elizabeth! You are strong, resilient, and beautiful. Someday we will have to sit down and talk about our experiences with food and eating (or not!) Love you, Aunt Cris

Bob Scrivner • Oct 9, 2019 at 11:47 pm

Outstanding introduction to pull the reader in on a subject that is hard to discuss. – Great Job Liz, keep talking about eating disorders and keep writing!

Greg Cusack • Oct 9, 2019 at 10:42 pm

Impressively written, Liz, with a powerful “you speaking directly to me” feeling! Extremely well done! I recognize that this took a significant measure of courage, as well as a remarkably balanced sense of self and the serenity you feel in being yourself. When I was 23 (a very long time ago now) I struggled for months with grave depression, and one of its many manifestations was the fear — inability, really — of eating in public. We can’t tell just by looking at someone what kinds of pressures, fears, or troubles are on their shoulders, but most of us have one kind or another “monkey” riding us at one time or another. I salute your candor, courage, and decency; I am proud of you. Peace and sincere best wishes to you!(P.S. I am a cousin of your mother’s mother.).

burgess • Oct 9, 2019 at 9:16 pm

What a clear, beautifully written description of the loneliness of many disorders that face adolescents and young adults. Crazy cool that you found the courage to be so open about your struggles!

Allison Todd • Oct 3, 2019 at 6:42 am

Thank you for your willingness to share your personal experience with so many. By removing the stigma and mystery, you normalize the recovery process and show others how they can support the people they love. Wonderful work!!

Morgan Hampton • Oct 2, 2019 at 5:10 pm

Proud of you Liz!