Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.

The Power of We

January 23, 2020

Their stories come from all over: Tanzania, Guatemala, Vietnam, Ethiopia, Burundi, Eritrea. They’ve all made America their home. But it’s not just them. American-born, immigration, refugee, indigenous — in these stories, we invite you to break down the barrier of “us” and “them.” This is…

The Power of We.

Photos by Marilyn Buente

The Power of We is our newest package story, featured in the issue “Home and Away”

The Power of We: Video

Promotional trailer for the package in our newest issue, “Home & Away.” See an inside look into how and why “The Power of We” was created.

See how and why we chose immigration as the focus of our latest issue.

Photos by Mia Breitenstein

Standing in front of the stables at Churchill Downs’ Backside on Nov. 19, Merlin Cano smiles while recounting her expectations of living in America. “When someone mentions America, the first thing to your head is New York — the big city, the pictures that you see,” she said.

Beyond the Spires

Learn how this Churchill Downs-based nonprofit lifts kids from one of Louisville’s hidden communities over their everyday hurdles.

Eleven-year-old Merlin Cano didn’t know what to expect as she walked into the chapel nestled between stables on the Backside at Churchill Downs. Lately, it seemed not knowing what to expect had become her new normal.

A girl approached Cano with a cheerful expression.

“Do you wanna play?” she asked.

Cano’s eyebrows furrowed. The words were gibberish to her.

She tried to reply but the problem was, having recently emigrated from Guatemala, Cano didn’t speak enough English to understand what the girl had said, let alone play with her. All she could do was look at the girl with a blank expression.

“They brought me here. I always say that because they didn’t ask if I was okay with it,” said Cano, now 18, laughing and referring to her parents. “Like, I didn’t know what this country was.”

Unfortunately for Cano and many other immigrants in the United States, this disconnect is

all too familiar.

Cano had imagined the entire country would be four million square miles of New York-esque skyscrapers, crowds of people, and bright, colored billboards.

Instead, as she got off theplane and set foot on American soil for the first time with her mom and siblings, Cano was greeted by the dreary parking garages of the Louisville airport and commotion of the concrete highway. For the first time, she met some of her much older brothers and sisters — most of whom she’d only ever seen in pictures.

“I remember thinking that she looks so different from the picture,” Cano joked, laughing as she recalled seeing her older sister for the first time. “Like, she looks better in the picture.”

Most of her family had already moved to the United States and gotten jobs as equine workers at one of Louisville’s greatest attractions, Churchill Downs.

But for Cano and her family, rather than oversized hats and mint juleps, the track is a place filled with dirt roads, stables, baby goats, and horses. Tucked just off Fourth Street, this community is known as the Backside.

When we — the writers, Annie and Katie — set foot onto the Backside, people greeted us with smiles and waves. We watched as workers groomed horses, cleaned out stalls, and people zoomed by on bicycles. A goat was perched near the corner of the stables. We immediately had our phones out to take pictures, but the workers paid no mind to the animal. They continued on with their work.

Many of the workers at the Backside are immigrants who came to the United States seeking financial stability. A good amount of them come to Louisville not speaking any English, and because of this, it is hard to adapt to life that occurs outside the track. That’s why many of the workers find themselves turning to a program that helps them in any way they can to succeed: the Backside Learning Center (BLC), an independent non-profit.

Nestled right behind a giant jumbotron and just steps away from the track, the BLC offers English as a Second Language (ESL) services, basic social services, and provides educational resources. Sometimes their clients need everyday things that many people take for granted, like translation services at a doctor’s appointment, help communicating with their child’s teacher at a parent-teacher conference, or legal support.

“There’s just this relaxed, open, friendly exchange that takes place. Even if it’s just somebody coming in to pick up their mail — we receive a lot of mail for the Backside workers. I like the community aspect — just the social aspect of it,” said Mariah Levine Garcia, the Family Resource Coordinator at BLC. Levine Garcia’s warm smile is often the first thing people see when they walk into the BLC.

Originally called the Klein Family Learning Center, the BLC opened its doors for the first time in 2004 and they have remained very, very busy. In 2019, 90 adults enrolled in ESL courses, 80 children and youth received homework help, and, since opening its doors, four students have gained U.S. citizenship. These statistics are great achievements for the BLC, but to people like Cano, these numbers represent more: their friends, their coworkers, and their community.

Cano and her family were introduced to the ESL program when she was 11, although she wasn’t able to attend their programs regularly until she was able to drive. At that point, Cano’s parents also started attending ESL classes.

Cano would attend the class with her parents, aiding both the teacher and her parents.

“I was the youngest in the classroom, just sitting there helping my parents,” Cano said, pointing to the bigger classroom across the hallway as we interviewed her.

These classrooms are adorned with Spanish-to-English dictionaries and walls of vocabulary like “balcony” or “receipt” — words so mundane many people don’t even remember learning them. This was in sharp contrast to what she encountered at Thomas Jefferson (TJ) Middle School and Iroquois High School, where she found the language barrier harder to overcome.

Despite spending a year at Newcomer Academy (see “Come As You Are” on page 52), the transition to TJ and Iroquois was still rocky. The combination of meeting some of her immediate family for the first time and adjusting to Louisville’s culture was close to overwhelming for Cano.

“At first it was really hard for me,” said Cano. “I felt really sad and everything, but then I started to like it.”

Once Cano got her driver’s license, she was able to appreciate little things like going out after school with her friends and trying restaurants all around Louisville.

“We would actually go to one of our teachers to ask, like, opinions about different places to go,” Cano said. “Good ones, and cheap.”

However, eating the ropa vieja at Mojito Tapas with her friends wasn’t always her top priority. Driving meant more familial responsibilities, like driving her parents around and translating for them at things like legal appointments. Cano also worked two jobs while attending Iroquois — one at Walmart and one on the Backside at Churchill Downs with the rest of her family.

So, while most high schoolers find themselves still in bed well into the morning on the weekends, Cano is wide-eyed and awake at 5 a.m., walking thoroughbred horses.

“Oh my god, I get ready in like five minutes and I would just take something to eat,” Cano giggled. “When I get to the barn, I eat it there. And we usually finish by nine with horses.”

Often times, Cano was straddled with responsibilities that many high schoolers in Louisville aren’t prepared to cope with. She was stretched thin between two worlds, but one place where she was able to find solace was the BLC.

As Cano got older, she realized that those classrooms — the same ones that she had spent countless evenings in, helping her parents learn English — could be a resource for her, too. So when the time came for her to start thinking about college, she knew exactly where to turn.

“I came here to ask them if they could help me with applying to colleges and maybe doing my FAFSA and all of that,” Cano said, referring to her college federal financial aid forms . “Because like, I had never done that before, and I couldn’t get the help at home.”

They helped Cano get into Jefferson Community Technical College (JCTC), where she is currently studying to become a nurse.

Cano kept returning to the BLC, not only to receive help, but to volunteer. Once she graduated high school, Cano was offered a job working as the Youth Activities Leader. Now, she works as a thoroughbred walker in the early morning, goes to classes at JCTC in the middle of the day, and helps lead the Front Runners program at night.

Front Runners is an after-school program that offers academic support and assistance to the children of the Backside workers. Annie, one of the writers of this story, is a current volunteer for this program.

Like Cano, the kids from Front Runners face the challenge of having to learn English while speaking mostly Spanish at home and translating for their parents. Front Runners aims to address these problems while still making sure the children are able to play and act like kids in a friendly environment. The program fosters curiosity, literacy, and mindfulness through group reading, drawing, and games.

“I love watching them grow and learn, and their curiosity, and just really learning from them and them learning from us. It’s a good feeling,” said Levine Garcia.

During one Front Runners meeting, the volunteers led the kids in a call and response. An energetic volunteer in her early 20’s cheered at the crowd.

“TARZAN!”

The kids giggled while repeating the name in a high pitched voice and trying to flex their scrawny arm muscles.

“SWINGIN’ FROM A RUBBER BAND!”

Their arms swayed above their heads, smiles stretched across their faces.

As the kids started entering each classroom, they were greeted with volunteers who helped them with whatever they needed. When we visited in early December, one group practiced times tables while others sat on the couch listening to a volunteer dramatically read “If You Give a Mouse a Cookie.”

In another classroom, one girl, Victoria (5), was focused on designing a colorful birthday card for her friend, Karen (6), at the next table filled with hearts and rainbows. She bounced from her seat, getting the exact color of pink she needed to make the card perfect — to make her friend’s birthday perfect. When she gave the card to Karen, Victoria was practically beaming. Karen lit up as her friend grinned. (Due to a request from the BLC, we have elected not to include the last names of minors.)

After homework and reading time, there’s snack time — the kids’ favorite. Here, the kids can munch on oranges or other fresh foods. But the most important part of Front Runners is the last 45 minutes: group time.

Group time usually starts with a check-in activity from Levine Garcia, where they practice mindfulness and reflection. Students are broken up into four groups: “Pre-K,” “K-2,” “3-5,” and the youth room (6th to 12th grades).

The youth room, normally filled with laughter and excited energy, was unusually quiet and dark the night we visited. Rows of computers illuminated the students’ faces. In the youth room, a local organization, Peace Education Program (PEP), was establishing their first after-school pilot program, called Youth Influencers, made for the students at Front Runners. According to Lijah Fosl, the program director, the program teaches students how to utilize social media in order to “challenge prejudice and have a positive influence on their communities through their personal stories.”

The BLC, including Front Runners, works with many local organizations to support the equine workers and their families who call Louisville home. This comes in the form of after-school programming that helps students discover their artistic side among other things. The BLC has also worked with well-known local foundations like Kentucky Shakespeare, Kentucky Refugee Ministries (see “Kickin’ It in Kentucky” on page 60), and the Food Literacy Project.

This youth room is where you’ll find Cano every Tuesday and Thursday evening. Everyone at the program knows Cano — she’s basically Front Runners royalty. She always seems to be talking to someone, sometimes with parents, sometimes with students, and other times, like when we visited Front Runners, talking to Levine Garcia.

A group of six kids have started to call her “Tía” (or “aunt” in Spanish). She calls them her adoptive nieces and nephews in return. Because Cano is closer to their age, she was in their position just a couple of years ago. She understands their thirst for independence and she understands what it’s like to be in their shoes.

“I feel like if I go up to any of the girls, they will just trust me and tell me how they feel, what’s bothering them and everything. But with the boys, it is a little harder. I don’t really know why. They probably need a male to talk to,” Cano said.

During a Front Runners session, when we asked Andira (15), a sophomore at Iroquois High School, if she wanted to participate in our interview, she looked at us like we were crazy.

“Are you sure? My English isn’t that good,” she said, blushing.

“She’s lying,” Cano, who had overheard, said. “Her English is very good.”

Andira only blushed harder.

The Backside at Churchill Downs is made up of immigrants and their families, supporting each other, just like how Cano cares for Andira. The BLC only bolsters that strength.

Cano can now help the kids at Front Runners who remind her of herself, walking into that chapel, unsure and unrooted. She helps them find their voice. She helps them find a setting that’s their own with others that will support and uplift them. She helps to build bridges between them — to inspire and connect their community.

Cano is not the same little girl sitting in that church years ago. She is not unrooted from her home, unsure of the people around her, and most importantly, uncertain of herself. She has been planted not only by the people of the Backside, her friends at Iroquois High School, and the BLC, but also the hard work she put in to make the best of her situation.

She has now grown from someone who looked for help, to someone who gives it. She has blossomed into a role model and a person who people flock to for advice and friendship — a person they trust.

“I tell them all the time,” said Cano. “If I’m able to help you, I will.”

Click here if you would like to volunteer at Backside!

Photos by Faith Lindsey

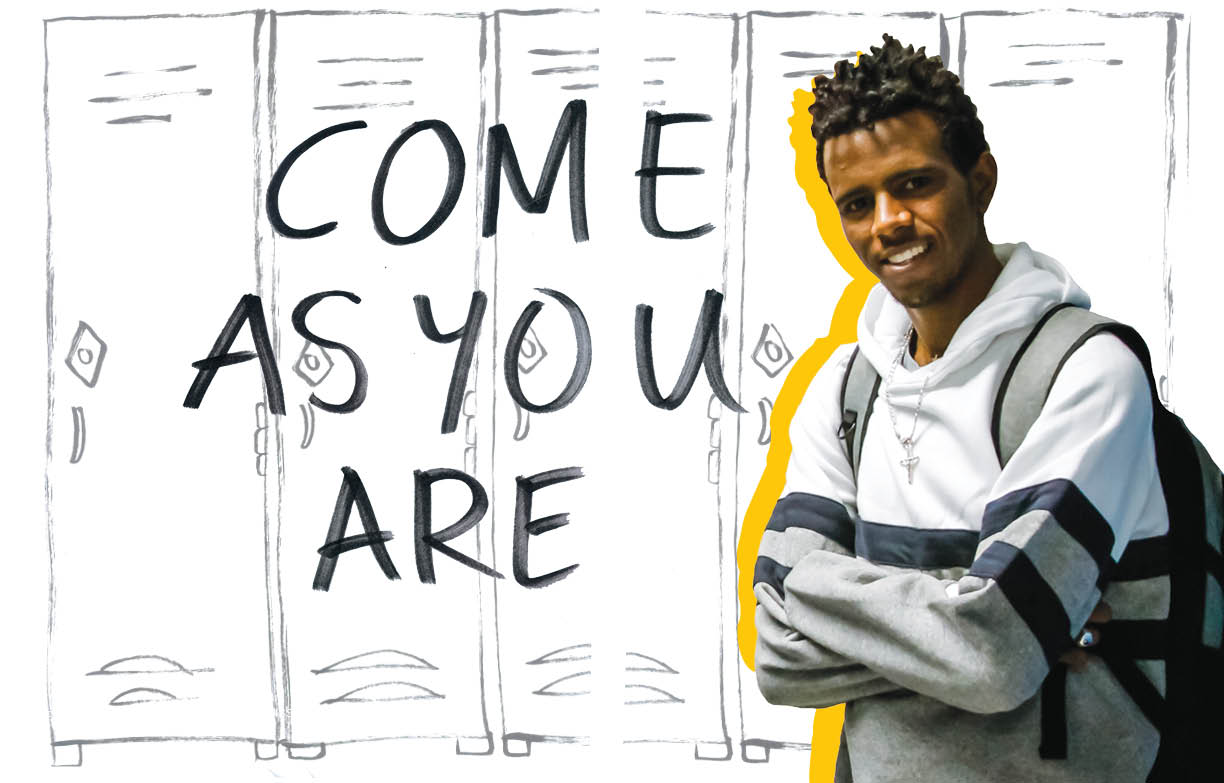

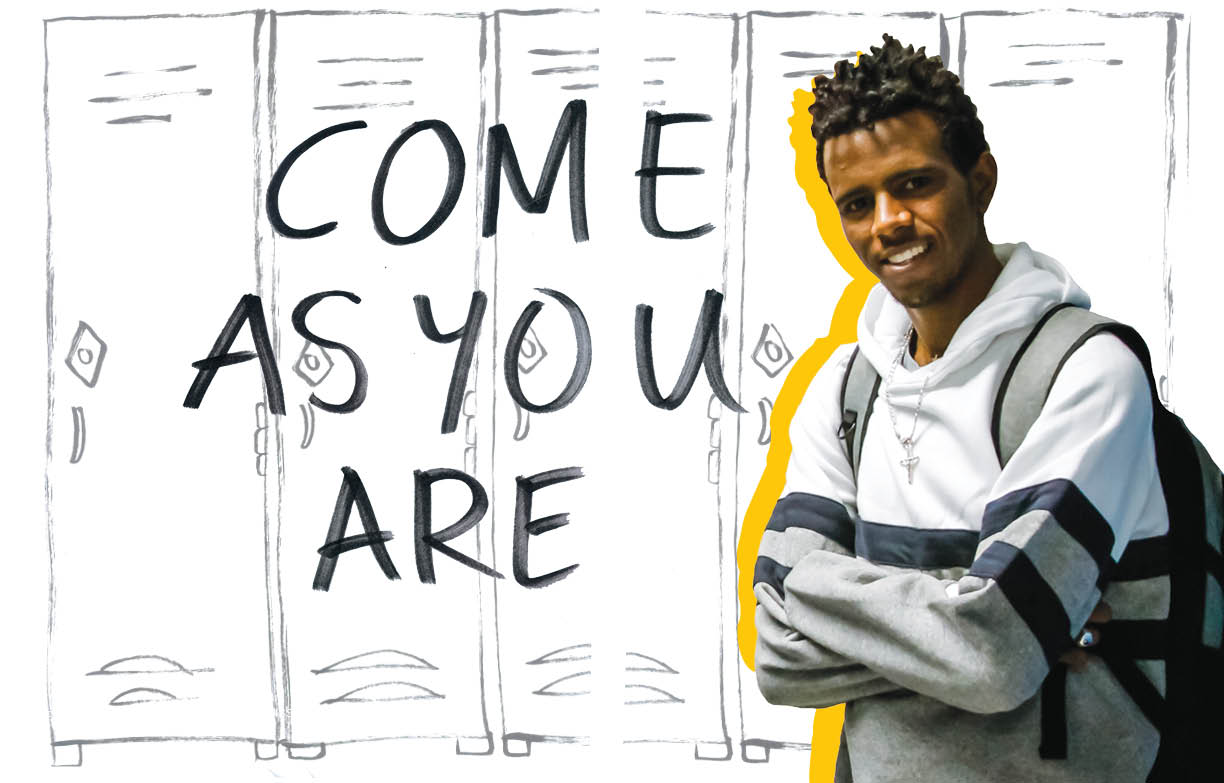

After fleeing his country due to the Eritrean-Ethiopean war, Newcomer Academy student Tesfalem Haile says he believes his education could change his life. “I want to be a doctor,” Haile, 20, said.

Come as You Are

Newcomer Academy helps students balance the pressures of a new culture, language, and lifestyle.

Four first-year students walked through the hallway side by side, nudging each other as they laughed at their own jokes. One spoke in an Arabic accent to another student who replied in a thick French accent. The other two boys communicated with Wolof and Vietnamese accents — all of them speaking the same language but putting their own twist on it. Their varying backgrounds didn’t create a barrier. Rather, this journey was something that they shared.

“I am the king!” 18-year-old Gisubizo Ndayishimiye yelled with a grin. His friends turned their heads and laughed as he puffed his chest out.

Amused, 17-year-old Boubacar Dieng replied, “You are no king; I’m the king!”

Tesfalem Haile, 20, joined in on the banter as he spoke over them, “I am the oldest, I should be king!”

Hoang Nguyen, who was 15 and a bit more reserved, watched them from the side as a light chuckle escaped him.

These students come from different places around the world: Ndayishimiye from Burundi, Dieng from Guinea, Haile from Eritrea, and Nguyen from Vietnam. They immigrated to the United States last May, and continue to adapt to their new

life and a new language. But in that hallway moment, all the barriers broke down.

The sound of their voices echoed through the hallway as they conversed carelessly in this new language. Ndayishimiye, Dieng, Haile, and Nguyen all continuously apologized throughout the interview for their mispronunciations, but when they were together, they laughed off the imperfections. To them, that was okay — being able to learn this new language together was enough.

As the bell rang, students of Newcomer Academy flooded the hallways and greeted each other. Haile’s friends approached him with beaming faces and outstretched hands. They entered the classroom, divided themselves among their linguistic groups, and began conversations in different languages that united each of them.

Newcomer is a middle-through-high school in eastern Louisville’s Klondike neighborhood that is dedicated to helping newly-immigrated students become proficient in English as they adapt to their new environment. The school helps students up to age 21. Currently, the school enrolls 655 students who speak 22 different languages.

The school is also unique for giving English as a second language (ESL) learners the opportunity to be part of an accepting community which allows them to communicate in their language to their teachers while learning to speak English. The majority of the teachers at Newcomer either speak English as a second language or are fluent in multiple languages. This advantage helps break down the linguistic barrier between teachers and students.

That day in class, it was September — still early in the year. Scott Wade, a teacher at Newcomer, decided to arrange the students so that they were sitting next to someone who came to America by different means: some by boat, some by bus, and some by plane. In a Nigerian accent, a student shouted “mix and mingle” to her classmates as they got situated in their new seats. The students no longer had a sense of ease on their face as they looked at each other for what was to come next. However, it was only their third class of the day and there was no time to fret over old seats. They all had presentations to give, which included sharing their age, native country, languages they spoke, and dreams for the future.

Haile became particularly jittery once his slide appeared on the board. He made his way slowly to the front of the room, looking straight ahead and avoiding the eyes of his classmates. At the age of 20, he was an older student in the class. However, his interactions sows that it didn’t hinder his ability to form relationships with his classmates.

Haile is from a small East African country, Eritrea. He boarded a plane to Ethiopia with his stepsister to escape the wars that had torn his home country apart and immigrated to the United States after living in a refugee camp for five years.

“Every day we have wars and every time people die,” Haile said.

The Eritrean-Ethiopian war was the final straw; Haile knew he had to leave. The war started in 1998 and ended in 2000,

but the two countries didn’t officially agree to peace until 2018. Just as his own country overcame its struggles, Haile was determined to be triumphant in his own battle.

“You have to learn because you have to change your life,

no one can help you,” Haile said. “If I have to change my life, I have to learn.”

Newcomer offers classes that help Haile and other students learn the complexities of the English language and culture. Classes like Wade’s Explorers Program take place every Monday. Students learn about current global events, even activism like that of Greta Thunberg and Malala Yousafzai, both prominent youth activists. During one class, the students watched a video about Thunberg and Yousafzai, but slowed it down so that they could comprehend each word of the video. They watched attentively, their eyes widened as they learned about the different ways these young women have made a place for their voice in the world.

Every student has their struggles, each one of them learning at a different speed.

Still, they were all newcomers, all of them tackling this new language together. The Explorers Program offers a place where students can focus on the direction they are headed during their next two years at Newcomer, while still appreciating the countries they originate from. During those two years, the students will gain many new life experiences and opportunities.

After school programs organized through the YMCA aim to create a welcoming and educational environment for Newcomer students. Volunteers and the YMCA staff organize soccer, basketball, and tutoring services for students. In addition, teachers like Wade and the current principal, Gwen Snow, play a part in the success of their students. In the past, Snow had been an art teacher at Newcomer and connected with her students through interactive activities, rather than traditional language conventions. One strategy Snow used to connect with and understand her students was a storyboard.

The activity involves “asking them to draw a storyboard of the events that happened, and have some different images that go with it. Under the images, they can start to generate words underneath,” Snow said.

Being able to form these narratives helps bridge the gap between students’ native languages and the English they’re learning. Many students who attend Newcomer come from Guatemala, Honduras, Cuba, Tanzania, and Rwanda, but no matter where they are from, they all have a story to tell.

That’s no less true for Abdurazak Ahmed, a Newcomer student from Kenya. Before coming to Newcomer, Abdurazak was nervous about handling the pressure of learning a new language and being singled out for not knowing English. But at Newcomer, Ahmed had teachers who helped him learn English and further develop his speaking abilities. He recalled the different methods teachers used in his native country versus here, in America. In Kenya, he explained. School was not prioritized, classes were small, and students had to pay for their education. Students waited for their teacher to enter the classroom as opposed to teachers waiting on the students. However, at Newcomer, Ahmed said has grown close to his fellow classmates and teachers.

“One thing we all have in common is that we are like brothers and sisters here, and even the teachers are like our parents. Newcomer is the place where I found myself and I feel comfortable,” Ahmed said.

Newcomer has helped provide opportunities for students since its start in 2008. Former Newcomer student, Nini Mohamed, also from Kenya, described his own experiences as a student there that first year. At the time, the school was still operating out of Shawnee High School. Mohamed was only at Newcomer for six months because of his rapid improvement, quickly transferring to Waggener High School. Even before starting at Newcomer, he remembers the feeling of getting his first backpack, something many kids have long forgotten.

“I used to go over to the Kentucky Refugee Ministry building, and what they do is they prepare you and make sure you have a backpack,” Mohamed said. “They make sure you have books, pencils, and as new as I was, it’s exciting to get a backpack of your own. I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I finally have a backpack!’ (See “Kickin’ It in Kentucky” on page 60 for more about Kentucky Refugee Ministries.)

Mohamed recently self-published a book called “The African in America” and is working toward his second book. He said that his first book’s purpose was to bring people together — specifically the African community.

“Since I published my book, I have helped four people write their own books, and that makes me feel good. It’s like you’re writing your own story but helping other people write their stories as well,” Mohamed said.

Mohamed believes Newcomer was an integral part of his own story. What he learned there helped launch his work as an author and motivational speaker. His achievements represent a fulfilled promise for the school, to connect students, bring them together, and lead them to bigger places. Though Mohamed, Ahmed, and Haile’s origins spread far and wide from different East African countries, the school has given them the tools to succeed in America, and has been vital in defining who they are growing to be; Mohamed an author, Ahmed a mechanical engineer, and Haile a doctor.

“In this book, I would like to share with you my life in between Africa and America,” Mohamed wrote in the second edition of his book. He goes on to say how “it is amazing how they love this country enough to do whatever it takes to get here” — illuminating the strenuous journey of making a once foreign environment a place they can call home, a place they can come as they are.

Photos by Mia Breitenstein

Saleh Ekuchi, 16, teases a friend by trying to kick the ball out of reach on Oct. 19. “When I just got here I started making friends from soccer and school,” Ekuchi said.

Kickin’ It In Kentucky

Leaving home was not his choice, but he found a new community with the help of a Louisville soccer program.

Rain pounded on the roof of a brick house. Outside, the air was chilly, but inside, it was warm, cozy, and dry while everyone scrambled around the kitchen to prepare meals for the family’s celebration.

Almost everyone.

Barely visible through the pouring rain was 14-year-old Saleh Ekuchi with his big brother and a few friends, running and playing with a makeshift soccer ball. With each step, their shoes sunk into the mushy ground.

Their mom called for them to come inside, but the boys continued laughing and treading through the oozing mud.

It was New Year’s Eve in Tanzania, and the boys did not want to miss out on the chance to celebrate with a game of soccer — even in the pouring rain.

“I can never forget that; it was so fun,” Saleh, now 17, reflected as we sat next to him on a bench outside of Iroquois High School.

We chatted with him about some of his favorite memories from home. Just as it was raining in Tanzania that New Year’s Eve, there was a light drizzle. It was enough to be noticeable, but not enough for an umbrella or a raincoat. On the field in front of us, a few members of his soccer team scrimmaged with a pair of portable goals; a little bit of rain wasn’t going to keep them from practicing.

Saleh’s parents are from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. His parents were no longer safe in the Congo, so in 1996 they moved to Tanzania, where Saleh and all of his siblings were eventually born. His family first lived in a refugee camp — Tanzania was never meant to be a permanent home for them. In 2017, Saleh was 14 years old when he, his five sisters, four brothers, and parents left Tanzania as refugees.

“When I left my country I was crying,” Saleh said. “I was happy and at the same time I was sad because I left my friends and my family.”

The Ekuchis made multiple stops before settling in Louisville, stopping in Kenya, Dubai, and Washington D.C., bringing only their clothes and a few sentimental items they could not leave behind.

“I had this chain right here for my religion, so I had to bring it,” Saleh said as he pointed to his red and white beaded necklace. “I brought my Bible with me and a book with my family pictures in it.”

When Saleh and his family got here, they found comfort in the services provided by Kentucky Refugee Ministries (KRM).

“They showed us how to get a Social Security card and how to get an ID. To go to the store, they give us food stamps and showed us how to use it. Sometimes they gave us clothes and shoes,” Saleh said. “Anything like what school you’re gonna go to, what bus you’re gonna take. We didn’t know anything when we just got here.”

KRM is a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing resettlement services to refugees, assisting them with their integration into our community. KRM provides families like the Ekuchis, access to resources and opportunities so their clients are no longer seen as outsiders, but an integral and unique part of our country and community.

“They love everybody — they don’t care if you are from here or there. They don’t care about skin color or anything,” Saleh said. “They don’t care if you are old or small, they are going to help you in any way.”

Many organizations similar to KRM believe refugees can benefit the community by becoming contributing members of society through employment and self-sufficiency. A study from the Fiscal Policy Institute found that “19 of the 26 employers surveyed — 73% — reported a higher retention rate for refugees than for other employees,” meaning refugees tend to stay with an employer longer than other hires. However, not all Americans feel that this validates their adoption into our communities. The Trump administration plans to place an 18,000 person cap on the number of refugees allowed into the country in 2020, the lowest since 1980 when Congress first created The Federal Refugee Resettlement Program. 2018 was the first year since the establishment of this program that the U.S. did not lead the world in refugee arrivals.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo delivered a press statement in which he supported Trump’s signing of the Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2020. According to him, the U.S. should prioritize the people already in the country who need assistance.

“Indeed, the security and humanitarian crisis along our southern border has contributed to a burden on our immigration system that must be alleviated before we can again resettle large numbers of refugees,” Pompeo said.

The seemingly never-ending national debate revolving around refugee and immigration policy is enough to make anyone feel overwhelmed. Here’s the good news: KRM is just one of the many nonprofit organizations committed to helping refugees build a better and safer life wherever they are resettled by catering to their basic needs to promote self-sufficiency and integration. Saleh has been in Louisville for two years now, and he says his family still receives help from KRM when they need it.

When Saleh met Mary Daly, his caseworker from KRM, she asked his name, where he was from, and the languages he spoke — but he had something more important on his mind.

“I asked how I can join a soccer team. They have a partnership with HYR and you can join a team. And two months later we joined the team at HYR,” Saleh said.

HYR stands for Highland Youth Recreation, the soccer league that Saleh and his brother joined. For Saleh, being part of a soccer team was key in finding a sense of community in Louisville – and a cure for his cabin fever.

“I didn’t have anything to do at home and it was summer. We didn’t have a car and we didn’t have anywhere to go. We were just sitting in the house and watching TV all the time,” Saleh said. “So as soon as we started playing soccer, I was very happy.” Saleh is one of many refugees who calls Kentucky home. Our state is a hotspot for incoming refugees from all over the world.

In the 2019 fiscal year, 1,323 refugees arrived in Kentucky, making it number five in the nation for total refugee arrivals. For Louisiana, a state with almost 200,000 more people than Kentucky, that number was 21. Louisville is an epicenter for a lot of these refugees, welcoming nearly half of those that have come to Kentucky since 2002.

Since he lives in a state and city with so many other people from similar backgrounds, Saleh believes it is important to clarify for native Kentuckians and Louisvillians what being a refugee means to him.

“There’s a difference between immigrants and refugees. We came as refugees. We didn’t have any choice. We didn’t make any choice,” Saleh said.

When Saleh and his family made it to Louisville, they didn’t know anyone. After just one week, different families were coming to meet his family. Coincidentally, one of them used to be their neighbors in Tanzania; the Ekuchis began to find a sense of community in a new country, away from home. However, it took Saleh a while to get used to how people act differently here than in Tanzania.

“You know in my country, you gotta talk to your neighbor. You got to say, ‘Hi, how are you? How did you wake up?’ But here it was a little bit different,” Saleh said. “When you wake up you don’t even talk to each other. You just look at your neighbor; you don’t even say ‘hi’ to them.”

According to Saleh, sports are also a lot different in Tanzania. Americans often grow up playing many different sports, but in Tanzania, soccer is the thread that binds people together.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re a girl or boy, we just play all of us together. You just make something up and start playing – you don’t worry,” Saleh said. “It doesn’t matter if it’s night or day, you can play soccer anywhere. So soccer is the best part of my country.”

HYR is a program where kids and teens ages four through 16 can play in divisions based on age. Patrick Fitzgerald, who grew up playing in the league, is the current director.

“I played in HYR in 1976, the very first season they had soccer and I’d never even kicked a soccer ball before. So that’s how I learned about soccer was playing with HYR. I played it for five years as a kid then I coached it for 15 years as an adult,” Fitzgerald said.

When Fitzgerald took over as director in 2017, one of his priorities was to diversify the league. He started by reaching out to KRM and, in January of 2017, HYR worked with KRM to get 20 international players involved in the program.

Fitzgerald explained to us why HYR is intentional in calling the KRM clients “international players” instead of “refugees.” Referring to them as refugees reinforces the stigma that they are outsiders, rather than vibrant additions to our community.

“There comes a point where you are a refugee and you are resettled, but then you are just a person who lives here. You may or may not still get some kind of services, but you’re not a refugee anymore,” Fitzgerald clarified.

There were still logistics in the program that needed to be smoothed out in order to assist the players and the needs of their family, such as transportation.

Since HYR is part of Highlands Community Ministries, they were able to use a church van to pick up kids whose families were KRM clients for practices and games.

“It’s not just that they can play in the league for free. We help them get some cleats, socks, and shin guards and get them transportation to practices and games,” Fitzgerald said.

Saleh was one of the players who received this assistance; he was overjoyed to be able to play on a soccer team because his family could not afford the high expenses of club soccer in the U.S. He rode in the van to games, learning more about American cultural norms and how to better communicate with his new teammates.

When Saleh joined the soccer program, he already knew French, Swahili, and Kibembe (a language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo), but his English was limited to his name and age. On the way to practice in the church van, his teammates would force him to speak English, using it as an opportunity to get him comfortable with the language, even if he made mistakes.

“Just talk. Nobody cares,” Saleh shrugged. “If you don’t practice, you’ll never know how to speak English. So I just started talking to them.”

When he started playing soccer for HYR, Saleh met a lot of friends, some of whom helped get him into a soccer club. Currently, Saleh plays for Iroquois High School, Falls City, and a team called Wakanda FC, where he plays outdoor soccer and futsal — a type of soccer played on a hard court with a smaller, weighted ball. Last summer, his Wakanda FC team travelled across the region, winning tournaments in Indiana, Tennessee, and Missouri.

“If I didn’t play soccer, I’d be so lonely staying at home all the time. I don’t like to watch TV, so I’d probably be sleeping all the time or using my phone. And I don’t think I would have any fun if I didn’t play soccer,” Saleh said.

Currently, Saleh is a referee for the younger leagues of HYR. Working with these young kids, he and the other referees spend almost as much time being a teacher as a ref.

“When they don’t know how to throw the ball, we gotta show them. We gotta teach them the rules. You cannot touch the ball with your hands!” Saleh laughed. “Sometimes when they play, they just take the ball and throw it! You gotta say, ‘You gotta use your feet!’”

Too often, people with differing opinions about immigration toss around the word “refugee” as a buzzword without thinking about what it means, or the people behind it who have faces to become familiar with, names to learn, and stories to tell.

Saleh’s story is to keep his focus on playing soccer, reffing for HYR, and adjusting to life in his new community.

“I just try to fit in with America. I just want to be like normal people,” Saleh said. “It doesn’t matter if I’m a refugee. I just gotta feel comfortable and try to fit in with other people.”

Luckily, the soccer pitch is a place where Saleh doesn’t have to try as hard to fit in.

Half-time for the HYR soccer game had ended, and Saleh headed out onto the field behind Atherton High School. We watched as a swarm of children surrounded him, reaching for the soccer ball at his feet. He pulled the ball back and kicked it up and over the head of one of the kids, who watched in amazement, as Saleh brought it back down behind him. The sound of laughter from Saleh and the children echoed through the air. People across the field watched Saleh as he showed off his impressive soccer tricks.

The sun was at its peak in the sky, shining on Saleh as he blew his whistle to resume the game. He was right where he wanted to be: teaching a new generation of kids to love soccer the way he does.

Becoming a referee for HYR has given Saleh the opportunity to earn a little money while giving back to the organization that helped him grow his passion in a new city. But it isn’t about the money.

“Even if it was for volunteering, I would do it ‘cause they helped me a lot,” Saleh said. “I would do anything for them.”

Photos by Faith Lindsey

After fleeing his country due to the Eritrean-Ethiopean war, Newcomer Academy student Tesfalem Haile says he believes his education could change his life. “I want to be a doctor,” Haile, 20, said.

Venez Comme Vous Êtes

La Newcomer Academy aide les étudiants à équilibrer les pressions d’une nouvelle culture, langue et mode de vie.

Note: This is a French Translation of the story “Come as You Are,” featured in the newest issue of On The Record. It was translated by Audrey Villon, a French teacher at duPont Manual High School

Quatre élèves de troisième marchent dans le couloir côte à côte, se donnant des coups de coude en riant à leurs propres blagues. Un des étudiants parle avec un accent arabe à un autre étudiant qui lui répond avec un accent français très prononcé. Les deux autres garçons communiquent avec des accents Wolof et Vietnamien — tous parlant la même langue mais chacun avec leur petite touche personnelle. Leurs origines différentes n’ont pas créé de barrières. Au contraire, ils partagent tous cette même expérience.

“Je suis Le Roi!” crie Gisubizo Ndayishimiye, âgé de dix-huit ans, avec un sourire. Ses amis tournent la tête et rient quand ils le voient bomber le torse.

Amusé, Boubacar Dieng, âgé de dix-sept ans lui répond, “Tu n’es pas le roi; je suis le roi!”

Tesfalem Haile, qui a dix-neuf ans, se joint à la plaisanterie en parlant au dessus de tout le monde, “Je suis le plus âgé, je devrais être le roi!”

Hoang Nguyen, âgé de 15 ans, un peu plus réservé, les regarde depuis le côté en laissant échapper un léger rire.

Ces garçons viennent tous d’endroits différents du monde: Ndayishimiye du Burundi, Dieng d’Ethiopie, Haile d’Erythrée, et Nguyen du Vietnam. Ils ont immigré aux Etats-Unis en mai dernier, et continuent à s’adapter à leur nouvelle vie et un nouveau langage. Mais pendant ce moment de complicité, toutes les barrières tombent.

Le son de leurs voix résonnent dans le couloir pendant qu’ils discutent avec insouciance dans cette nouvelle langue. Ndayishimiye, Dieng, Haile, et Nguyen se sont excusés en continu durant l’entretien pour leurs erreurs de prononciation, mais quand ils sont ensemble, ils choisissent de rire de leurs imperfections. Pour eux, tout va bien – être capable d’apprendre cette nouvelle langue ensemble est suffisant.

Au retentissement de la cloche, les étudiants de la “Newcomer Academy” inondent les couloirs et se saluent. Les amis d’Haile s’approchent de lui avec des visages radieux et les mains tendues. Ils entrent dans la salle de classe, se divisent entre leurs groupes linguistiques, et commencent des conversations dans les différentes langues qui les unissent les uns aux autres.

Newcomer est une école du secondaire, située dans le quartier Klondike de Louisville, qui est uniquement dédiée à aider les étudiants nouvellement immigrés à maîtriser l’anglais alors qu’ils s’adaptent à leur nouvel environnement. L’école offre des opportunités scolaires pour aider les immigrants jusqu’à l’âge de 21 ans. Il y a actuellement 655 étudiants inscrits représentant 22 langues différentes parlées.

Bien qu’ils parlent des langues différentes, les étudiants ont l’opportunité de faire partie d’un communauté tolérante. Ils communiquent dans leur langue avec leurs professeurs tout en apprenant à parler anglais. La majorité des enseignants à Newcomer parlent soit l’anglais comme deuxième langue ou parlent couramment plusieurs langues. Cet avantage aide à faire tomber la barrière linguistique entre enseignants et élèves.

Une fois le cours commencé, Scott Wade, un professeur de Newcomer, divise les élèves de manière à ce qu’ils soient assis à côté de quelqu’un qui est venu en Amérique par différents moyens: certains en bateau, certains en bus et d’autres en avion. Dans un accent nigérien, un étudiant crie «mélangez-vous et allez parler aux autres» à ses camarades de classe alors qu’ils sont installés dans leurs nouveaux sièges. Les élèves ne sont plus à l’aise et se regardent les uns les autres en se demandant ce qui va suivre. Cependant, ce n’est que leur troisième classe de la journée et ils n’ont pas le temps de s’inquiéter de leurs anciens sièges. Ils ont tous des présentations à faire, à propos de leur âge, de leur pays d’origine, des langues qu’ils parlent et des rêves qu’ils ont pour l’avenir.

Haile, un étudiant de Newcomer, devient particulièrement nerveux une fois que sa diapositive apparaît sur le tableau. Il se dirige lentement vers le devant de la salle, regardant droit devant et évitant le regard de ses camarade de classe. Contrairement aux autres élèves de sa classe, il n’a pas l’âge typique d’un lycéen. Cependant, cela n’entrave pas sa capacité à nouer des relations avec ses camarades de classe. Haile vient d’un petit pays d’Afrique de l’Est, l’Érythrée. Il est monté à bord d’un avion pour l’Éthiopie avec sa demi-soeur pour échapper aux guerres qui ont déchiré son pays d’origine et a immigré aux États-Unis après avoir vécu dans un camp de réfugiés pendant cinq ans.

“Chaque jour on a des guerres et chaque fois des gens meurent,” Haile dit.

La guerre entre l’Erythrée et l’Ethiopie est la goutte qui a fait déborder le vase; Haile a su qu’il devait partir. La guerre a commencé en 1998 et a fini en 2000, mais les deux pays ne sont parvenu à un accord de paix officiel qu’en 2018. De la même manière qu son pays est arrivé à surmonter ses défis, Haile était déterminé à triompher dans sa propre bataille.

“Vous devez apprendre parce que vous devez changer votre vie. Si je dois changer ma vie, je dois apprendre,” dit Haile.

Newcomer propose des cours qui aident des étudiants comme Haile à apprendre les complexités de la langue et de la culture anglophone. Chaque lundi, des cours comme “Wade’s Explorers Program” réunissent des élèves qui viennent récemment de finir un périple que peu de personnes peuvent imaginer – immigrer dans un nouveau pays.

Dans ce programme, les élèves apprennent sur les actualités mondiales et l’activisme. Ils entendent parler de Greta Thunberg et Malala Yousafzai; deux jeunes activistes connues. Pendant la classe, les élèves regardent une vidéo à propos de Thunberg et Yousafzai, au ralenti afin de comprendre chaque mot de la vidéo. Ils regardent attentivement, les yeux grands ouverts en découvrant les différentes façons dont ces jeunes femmes ont fait entendre leur voix à travers le monde.

Chaque élève expérience ses propres difficultés, chacun apprenant à son rythme. Ils sont tous encore de nouveaux venus, apprenant tous ensemble cette même langue.

Le programme Explorers offre un nouvel espace où les élèves peuvent se concentrer sur la direction qu’ils veulent suivre pendant les deux prochaines années à Newcomer, tout en continuant d’apprécier les pays dont ils sont originaires. Pendant ces deux ans, les élèves feront de nouvelles expériences de la vie et auront de nouvelles opportunités. Après l’école, des programmes organisés par le YMCA visent à créer un cadre accueillant et éducatif pour les élèves de Newcomer. Des volontaires et le personnel du YMCA organisent des entraînements de football, de basketball, et des services de tutorat pour les élèves. En outre, des profs comme Wade et la directrice de Newcomer, Gwen Snow, jouent un rôle dans le succès de leurs élèves. Autrefois, Snow était professeur d’arts plastiques à Newcomer et établissait un contact avec ses élèves à travers des activités interactives, plutôt qu’à travers des conventions linguistiques traditionnelles.

“Nous pouvons leur demander de créer un scénario des événements qui ont eu lieu, et avoir des images pour l’accompagner, afin de générer des mots pour raconter l’histoire,” explique Snow.

Tous les élèves de Newcomer parlent une ou plusieurs langues en plus de l’Anglais. La majorité d’entre eux viennent du Guatemala, du Honduras, de Cuba, de Tanzanie, ou du Rwanda. Peu importe d’où ils viennent, Ils ont tous une histoire à raconter.

Cela est également vrai pour Abdurazak Ahmed, un étudiant de Newcomer qui vient du Kenya. Avant d’arriver à Newcomer, Abdurazak était nerveux concernant la pression d’apprendre une nouvelle langue et la possibilité d’être exclu pour ne pas savoir parler l’anglais. Toutefois, à Newcomer, Ahmed a des professeurs qui l’ont aidé à apprendre l’anglais et à développer son aptitude à parler. Il se rappelle des différentes méthodes que ses profs utilisaient dans son pays d’origine, par rapport à ici—aux États-Unis. Au Kenya, l’école n’était pas priorisée, les classes avaient peu d’étudiants, et les étudiants devaient payer pour leur propre éducation. Les étudiants attendaient que leur professeur entre dans la salle de classe, plutôt que l’inverse. Toutefois, à Newcomer, Ahmed est devenu l’ami de ses camarades de classe et de ses professeurs.

“Une chose que tout le monde ici a en commun, c’est que nous sommes tous comme des frères et sœurs, et même les profs sont comme nos parents. Newcomer est le lieu où je me suis découvert et où je me sens à l’aise,” dit Ahmed.

Newcomer continue à offrir des opportunités aux étudiants depuis son lancement en 2008. Nini Mohamed — un ancien étudiant de Newcomer, également originaire du Kenya — décrit ses expériences pendant cette première année d’opération. A l’époque, l’école fonctionnait au sein même du lycée Shawnee. Mohamed n’est resté à Newcomer que pendant six mois grâce à ses progrès très rapides, et a été transféré rapidement au lycée Waggener. Avant même de commencer à Newcomer, il se souvient de l’émotion de recevoir son premier sac à dos — quelque chose que la majorité des gens ont oublié depuis longtemps.

“J’avais l’habitude d’aller dans le bâtiment du Kentucky Refugee Ministry. Ce qu’ils font est qu’ils vous préparent et s’assurent que vous avez un sac à dos,” dit Mohamed. “ Ils s’assurent que vous avez des livres, des stylos, et malgré le fait que j’étais nouveau ici, j’étais tout excité de recevoir mon propre sac à dos. Je me suis dit “Oh mon Dieu! J’ai finalement un sac à dos.”(Voir “Kickin’ it in Kentucky, pg. 60)

Mohamed a récemment publié un livre intitulé “The African in America” et écrit maintenant son deuxième livre. Le but de ce premier livre est d’unir les gens — en particulier la communauté Africaine.

“Depuis que j’ai publié mon livre, j’ai aidé quatre personnes à écrire leur propre livre, et cela me rend heureux. C’est comme écrire ta propre histoire mais cette fois — ci tu aides d’autres personnes à écrire leur propre histoire.” dit Mohamed.

Newcomer fait partie intégrante de l’histoire de Mohamed. Ce qu’il y a appris lui a permis de se lancer dans une carrière d’écrivain et de conférencier spécialisé en développement personnel. L’école a connecté ces élèves, les a unis, et va les guider vers de nouveaux horizons.

Mohamed, Ahmed et Haile venaient des quatre coins de l’Afrique de l’est avant d’arriver à Newcomer. Cette école leur a donné les outils nécessaires pour réussir aux États-Unis, et a joué un rôle primordial pour déterminer leur vision d’une future carrière; Mohamed comme auteur, Ahmed comme ingénieur mécanique, et Haile comme docteur.

“Dans ce livre, je voudrais partager avec vous ma vie entre l’Afrique et les Etats-Unis”, Mohammad écrit dans la deuxième édition de son livre. Il continue en disant “C’est incroyable à quel point ils aiment ce pays et sont prêts à tout faire pour y vivre,” — mettant ainsi en lumière le chemin difficile que ces personnes entreprennent, transformant peu à peu un environnement étranger en un lieu familier, un endroit où ils peuvent venir tels qu’ils sont.