Digging Up Dirt

A first-person investigation into and facts behind the “Save Bernheim Forest” movement.

Photos by Mia Breitenstein

John Woodhouse and Lillian Metzmeir dug up the dirt to uncover the shady situation surrounding Bernheim Forest in Louisville.

For us, it was the signs. That was our first encounter with the “Save Bernheim” movement.

Scattered across our everyday landscape were these yellow, almost fluorescent-looking yard signs. Displayed across them, the phrase: “SAVE BERNHEIM FOREST.” So accustomed to seeing these in our daily life, we’d grown fairly numb to the message behind them. And frankly, we didn’t really care.

When our magazine assigned us a story centered around the “Saving Bernheim” movement, we were conflicted. While we were excited to have a new story and get a chance to write, our enthusiasm was met with a sense of indifference. As a duo, we (Lillian and John) knew virtually nothing about the movement. All we had were those signs. That repetitive part of our everyday commute had become something that now required our full understanding and attention.

To comprehend the issues at hand though, we had to answer the most basic question: What is Bernheim? While we’d been to the forest once before, we couldn’t have given you any kind of formal definition at the time.

Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest is over 16,000 acres, or about 25 square miles, of land near Louisville that’s home to some of Kentucky’s most important and diverse wildlife. Along with being both education and conservation-based, families both in and out-of-state visit the forest to hike beautiful trails, check out the elaborate art installations — like the fully repurposed sculptures of forest giants — and observe the park’s breathtaking natural landscape.

Last year, Bernheim celebrated its 90th year as part of Kentucky’s ecosystem. Amidst the forest’s year of celebration and pride, they’ve faced two major challenges, both of which have received substantial media coverage and public feedback.

The first of these two obstacles, the one that we made the most sense of, was the study by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet of proposed interstate routes, some of which would go directly through Bernheim. Immediately, this caught us by surprise. It was incomprehensible to us that an interstate, no matter the size, could be allowed to cross through a place like Bernheim.

“The interstate would be devastating. They would literally remove an entire knob or two — an entire hill,” said Mark Wourms, Executive Director at Bernheim, when we interviewed him in October.

This completely shook the people of Bernheim and had activists and community members up in arms. We contacted the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet to gain their perspective on the study, but before they were able to give us a response, the problem seemingly vanished.

That was because in October, then Governor Matt Bevin and the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet ruled out Bernheim as a possible route, issuing a statement assuring no parts of Bernheim would be affected by these routes, to the relief of Bernheim employees and forest dwellers alike.

At the same time that the interstate commotion began to fizzle out, our confusion around the second project had only just started. At first, the issue seemed simple. Louisville Gas and Electric utility company (LG&E) designed a natural gas pipeline — approved in 2017 — that would go through Bernheim’s Cedar Grove Wildlife Corridor. According to LG&E’s website, the pipeline is 12 miles long and about 12 inches wide. According to Wourms, it would cover about eight acres of Bernheim’s land. Its purpose is to provide the citizens of Bullitt County with natural gas, extending out from an existing LG&E natural gas transmission line. The reason for this is that LG&E claims the current Bullitt County natural gas pipeline is maxed out and needs more capacity.

The issue? According to Bernheim, the corridor of land that this pipeline would be cutting through is conserved in order to protect the natural features on it.

“The impact is loss of forest, loss of habitat for rare and endangered bat species… it would directly cut across a number of springs and it would cross one of the cleanest creeks in the area,” Wourms said.

During a meeting with our editors to gather and discuss ideas for our story, we did some initial research using different news media outlets and sources in the state. Across all mediums, we were met with essentially the same message: Bernheim is under threat.

“It would be approximately a 75-feet-wide swath of land for 12 miles that they would have a permanent easement on which means that they will control that land forever,” Wourms said. “It means they will not allow any trees to grow on that land forever. And you know, it’s a permanent scar and will impact water and groundwater throughout that length.”

When we searched the website posted on the “SAVE BERNHEIM” signs, the looming issues facing the park became much more apparent to us. Repeated on the site was not just that Bernheim was in danger, but how dire the effects would be on the forest. Bernheim was calling for support, not just to “Save Bernheim Forest,” but to protect all conservation land — to set a precedent for future threats from corporations to forests and conservation land across the country. In an opinion piece published in the Courier-Journal by Andrew Berry, Director of Conservation at Bernheim, Berry said: “And let’s remember, this dangerous precedent of breaking a conservation easement makes this a bigger issue than just Bernheim. We are fighting for conservation protections everywhere at a very pivotal moment in time for the environment and our future as a planet.”

We began to tackle the story with the only angle we assumed was correct — that we must save Bernheim.

Research and Roadshows

We headed to Quest Outdoors, a Louisville store that sells basically anything you need for whatever outdoor escapade you may be planning, to learn more about the threats to the forest at a “roadshow” organized by Bernheim employees. The roadshows are a way for Bernheim to explain their “side of the story,” as Berry put it. He and Amy Landon, Communications and Marketing Director at Bernheim, travel to locations all throughout the Commonwealth to explain possible threats to the forest.

At the roadshow, there was a table with the signature yellow signs along with two stacks of petition letters — one stack addressed to the Kentucky Cabinet of Transportation and one to LG&E. During our roadshow visit, we, along with dozens of other community members, signed these letters without hesitation. Almost mindlessly, we had jumped into an 8,500 strong movement that we didn’t know or understand enough about. Admittedly, we should’ve waited a little longer to fully to take a position.

This meant more research.

“LG&E has been very effective at getting their side of the story out,” Berry said.

This is true. With a quick Google search containing keywords such as “LG&E pipeline,” LG&E provides the public with an informational webpage that contains project details, answers to frequently asked questions, and even a “Fact vs. Fiction” tab that directly refutes misinformation.

On the website, LG&E has labeled themselves as “long-time supporters of Bernheim” and claims they worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to “ensure that we are making decisions that protect threatened species and are least impactful to the environment.”

There is also a map of Bernheim that shows what part of the land the approved LG&E pipeline would go through, along with an existing crude oil pipeline and electric lines. While on this map, we discovered that the route of the pipeline extension closely follows a pre-existing electric line that has no affiliation with LG&E. According to the website, the pipeline route covers 0.03% of Bernheim’s land.

After attending the roadshow, we talked to Natasha Collins, Director of Media Relations at LG&E, hoping to gain some clarity regarding the timeline of events and pipeline approval.

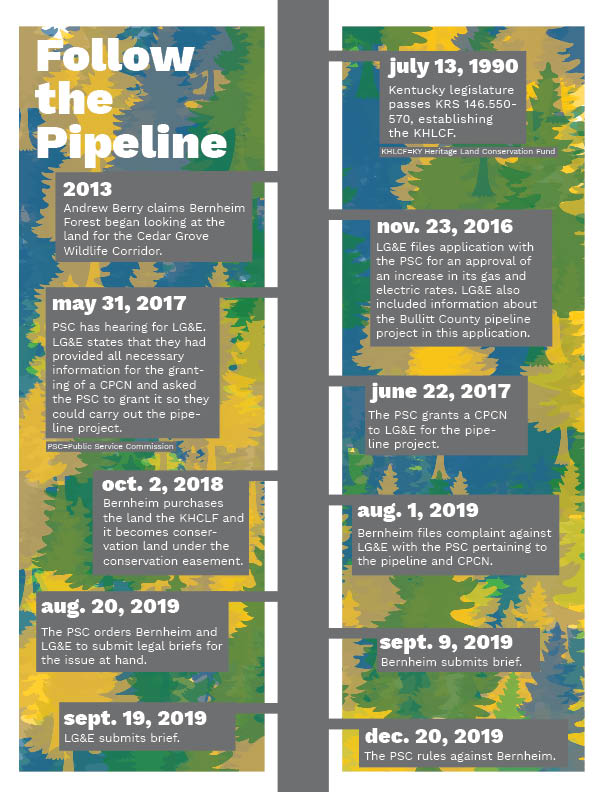

“This was a part of a filing we had before the commission in 2016, and the commission approved this project in 2017,” Collins said.

The commission Collins referred to is the Kentucky Public Service Commission (PSC). The PSC is a board of three people responsible for regulating rates and services regarding utilities. Think: electricity, water, sewage, natural gas, and so on.

Initially, we had the question many others did — why can’t LG&E choose a different route, one avoiding one of the state’s most highly regarded and popular conservation lands? Collins told us changing the already approved route would take five to seven years with an increased cost to customers.

“We believe that the path that we have chosen, with regard to the route and in regard to the planning, is the best path forward for being able to serve the community,” Collins said.

Collins informed us of an even bigger detail that we, along with much of the public, weren’t fully aware of. Not only is this land closed to the public and used solely for conservation purposes, Bernheim purchased it after the PSC approved LG&E’s pipeline.

That seemingly simple fact was like a puzzle piece that we’d been missing. It had baffled us that under any circumstances LG&E could even propose a project like this. After all, this forest was founded and continues to be run in the name of conservation. A pipeline built directly through it seemed unfathomable. But it made sense if the land didn’t belong to Bernheim when the project was approved.

After speaking with Collins, we gained an entirely different perspective. She opened our eyes to an idea we hadn’t yet considered:

Could LG&E be in the right?

We immediately took our newfound knowledge to our editors. In just a few minutes, our outlook had changed entirely. The once adamant advocacy tone was gone from our conversation, replaced by an almost accusatory one. We now needed even more research and had to take an honest look directly into everything that confused us about the issue.

In interviews and public statements alike, Bernheim has painted a picture that LG&E had been “secretly planning” this pipeline.

According to Berry, the beginning of the land-buying process actually started in 2013, when they began to look at possible conservation land to purchase. Bernheim finally bought the land, called Cedar Grove Wildlife Corridor, in October 2018 after receiving funding in 2017. 2017 was also the year the PSC approved LG&E’s pipeline project. Bernheim placed conservation easements and deed restrictions on the land in October 2018, too.

“Those two things are something you use as a landowner to ensure that certain things don’t happen on it,” Berry said.

A conservation easement, according to the environmental organization Land Trust Alliance, is “a voluntary legal agreement between a landowner and a land trust or government agency that permanently limits uses of the land in order to protect its conservation values.” What does this mean in regards to the pipeline? Berry claims that the easement means Bernheim can “never destroy the land and its natural features.” Now, this is where things get tricky.

Lost in Legality

We weren’t sure where to go. Bernheim told us one thing, while LG&E told us something completely different. After receiving little documentation from either side — besides vocal complaints and arguments — we decided to take verification into our own hands. At one of our staff worknights, we asked for the help of our staff’s “resident legal fairy,” Sky Carroll. Sky is the Content Director for the magazine, and has more legal knowledge than the two of us combined — fueled by her participation in youth government conferences like Kentucky Youth Assembly. While our only intention for asking for Sky’s help was to clear up our legal confusion, she became an integral part of our entire story. Suddenly, our duo became a trio, and just in time for things to get much more complicated.

We started with a simple Google search: “LG&E Bernheim lawsuit.” After some search adjustments and a few clicks later, we found an LG&E legal brief for the PSC.

While skimming that document, something kept coming up: Case No. 2016-00371. This called for another Google search. This took us directly to the Public Service Commission’s website, where we found endless links to documents having to do with Case No. 2016-00371 came up. We gave up on finding any pertinent links after a few minutes and went back to reading the same brief from LG&E to the PSC.

In this brief, another phrase seemed to be in every few sentences: Certificate for Public Convenience and Necessity, or CPCN. Another search.

A CPCN is a certificate that can be granted by the PSC to a developer before they provide utility services, like gas or electric services, to the public. So it makes sense that LG&E would need one before building the natural gas pipeline. Back to that later.

We were still pretty unsure of the timeline of events. When did Bernheim get the land? When did LG&E get approval? And of course, who was in the right, if anyone?

Bernheim claimed they began looking at the land in 2013, but we couldn’t find any documentation to back that up. Plus, “looking for land” doesn’t equate to ownership. After following up with Berry for some clarification, he said that “work on building the Cedar Grove wildlife corridor started much earlier than the actual purchases” and “these discussions with landowners, funding, and due diligence time periods take many years for conservation projects.”

In order to find documentation of the purchase, we found the conservation easement previously referenced — but this was no easy stroll through the forest.

When discussing visitor access to the land, LG&E referenced quotes from the easement in their brief. We couldn’t find any easily accessible copies of this easement online, but in one of the footnotes, we found that it was physically housed in the Bullitt County Clerk Office.

So on Dec. 4, we took a trip to Bullitt County.

After mistakenly walking into the library and then aimlessly wandering around outside, we finally ended up in the right place — but not before going up to the wrong desk first. Searching computer records was no easy feat, and we weren’t making any progress. Then, Lillian brought out LG&E’s brief and found that they listed the actual record book that the easement was in, which happened to be sitting right beneath the desk we were in front of. We pulled out the book, nervously flipped through hundreds of pages, and there it was. After a brief celebration of what seemed like a detective-like accomplishment, we took pictures of the 18-page document and were on our way back to school for a few hours of close reading.

The PSC granted this easement on Oct. 2, 2018 — after the PSC approved LG&E’s pipeline in June 2017. However, on page five, it says, “It is the purpose of this Easement to conserve and help ensure the continuation of the conservation values of the Property.” In other words, this easement is what made the land in question — the Cedar Grove Wildlife Corridor — conservation land.

Essentially, this means that the land would now have restricted uses and it and the species there couldn’t be disturbed in any way, other than approved activities. Page five also says, “There shall be no public visitor activities at the Property,” except for previously authorized management activities and approved scientific research. This idea constituted one of LG&E’s main justifications for their pipeline project — no one would be allowed on the land it would go through.

However, the most important part of the easement might be in the first few paragraphs, where the Kentucky Heritage Land Conservation Fund is mentioned. Page two reads: “The Property was acquired in part with Kentucky Heritage Land Conservation Fund (“KHLCF”) money…” The KHLCF was established through KRS chapter 146.550-570. In KRS 146.750, it identifies what money in the fund can be used for, and says that money can be used to buy land defined in KRS 146.560. KRS 146.560 classifies those lands as:

“Natural areas that possess unique features such as habitat for rare and endangered species;

Areas important to migratory birds;

Areas that perform important natural functions that are subject to alteration or loss; or

Areas to be preserved in their natural state for public use, outdoor recreation and education.”

KRS 146.570 also states that “Lands acquired shall be maintained in perpetuity for the purposes set out in KRS 146.560.” In other words, land purchased with KHLCF money is supposed to be kept as conservation land.

But what happens when that conservation land was already approved for a natural gas pipeline constructed by LG&E? On the other hand, what about when the land is home to endangered bats and a rare species of snails? Should LG&E’s project approval even matter?

We weren’t sure, either. That’s what’s still developing. On Aug. 1, Bernheim filed a complaint with the PSC (remember: a board that handles rates and services pertaining to utilities) explaining their discontent with LG&E’s actions regarding the natural gas pipeline that would go through the territory Bernheim now owned. The PSC received it on Aug. 2. The complaint marked the beginning of Case 2019-00274. Then the PSC ordered Bernheim and LG&E to submit legal briefs on the matter — why they were in the right and the other was in the wrong.

Throughout this process, Bernheim alluded that LG&E had been “secretive” about getting approval for their pipeline and that they didn’t follow proper guidelines. We still didn’t know exactly what this meant or have any details. So, we searched for them ourselves on the PSC’s website.

Bernheim alleged that LG&E had buried their application for a CPCN to approve their pipeline in an application to the PSC about increasing their gas and electric rates. Turns out, this claim did have some merit. In Case 2016-00371 with the PSC, the one we’d given up searching through earlier, there’s a roughly 100-page document that seems to be about gas and electric rates. But this wasn’t all that was there. On pages 31 through 35, the PSC briefly mentions the Bullitt County pipeline plans and then expresses consent to granting a CPCN for the project. You wouldn’t expect it to be there unless you knew it was there. After all, the application and document was primarily about gas and electric rates. Whether LG&E combined the two applications simply because it was easier or to deceive Bernheim — as Bernheim claimed — we don’t know.

Further, regarding CPCNs, KRS 278.020, yet another Kentucky law, states that after a CPCN application is filed, the PSC must hold a public hearing for all “interested parties” to the project at hand. On May 31, 2017, there was a hearing, but Bernheim wasn’t there. Bernheim claimed that they should’ve been present at the hearing and that LG&E should’ve notified Bernheim of their CPCN application. But remember, Bernheim had no conservation rights to this land at the time of the hearing.

Once we had all of this information, we needed to make sure we had interpreted everything correctly. The wealth of knowledge that we now had at our disposal was confusing and, at times, created a fog around the entire case. Our adviser recommended an environmental lawyer to help clear things up. An impartial opinion from someone with credibility. So that’s exactly what we did.

On Dec. 17, we headed to Lexington.

We met with Bethany Baxter, an associate attorney at Joe F. Childers and Associates, and laid out our collection of documents. We guided her through every piece of legal text that we’d accumulated, asking clarifying questions all along the way. To our relief, she found that our interpretations of the documents were right, and we’d been on track thus far.

In the end, Bernheim had these complaints:

LG&E did not file a separate application for a CPCN for the pipeline project.

Bernheim representatives were not present at the PSC hearing.

Bernheim was entitled notification of LG&E’s application for a CPCN.

However, on Dec. 20, the PSC rejected Bernheim’s complaints. Essentially, the PSC didn’t think Bernheim has successfully made their case against LG&E. They also said that Bernheim was not an “interested party” at the time of the hearing since it wasn’t their conservation land.

Since the whole issue was whether the PSC had made the right decision in granting a CPCN through LG&E’s rate application, we felt like the PSC wouldn’t be likely to change their original decision. Bernheim apparently saw this coming too, as they said in a statement: “They were considering their own prior decision,” and labeled the PSC’s decision as “unfortunate but not entirely surprising.”

Whether LG&E will build their natural gas pipeline soon is unclear, as other issues are still playing out. For example, LG&E still needs some permit approvals and is still pursuing eminent domain lawsuits against landowners before beginning pipeline construction.

Bernheim also said in their statement, “This decision is in no way the end of this issue or our fight to protect Bernheim’s land and conservation easements,” making one thing certain: Bernheim is not backing down.

Concerning Conservation

There comes a point where, when dealing with the legality of a situation, you have to take a step back. In the end, there’s who is correct — and who is right. At the root of this entire fight between LG&E and Bernheim is a forest. Throughout the months that we’d been researching, writing, and working on this piece, the fact that there’s a real forest with a real pipeline threatening it became lost to us.

In the same few months that we found ourselves engrossed in a local environmental threat and dispute, the international movement for environmentalism and climate justice took the global stage. Over the last year, a 17-year-old Swedish activist, Greta Thunberg, became the face of the movement, beginning with her decision to skip school to strike for climate justice. Since then, she’s addressed the United Nations and urged the world to join the fight for climate justice.

At the World Economic Forum in January 2019, Thunberg spoke on our Earth’s current climate and environmental state.

“I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if the house is on fire. Because it is.”

Bernheim Forest is, in a sense, on fire. And as small as the flame of this pipeline seems, the loss of conservation land anywhere should concern us in the age of climate change.

Just this year, the United States Department of the Interior approved construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline that will go through Montana. This pipeline is part of the Keystone Pipeline System, which transports over 35 million gallons of crude oil from Canada to the U.S.

Like Bernheim, supporters of conserving natural land have used both lawsuits and public protests to challenge the pipeline’s construction. The over 10 year long fight between a coalition of Native Americans and environmentalists, and one of North America’s largest energy corporations, TC Energy, has stood as a symbol in the struggle against corporate dominance over our environment that’s become far too common.

Movements like Saving Bernheim, the protests against the Keystone XL Pipeline, the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access pipeline in North and South Dakota, the protests against the Mountain Valley pipeline in both West Virginia and Virginia, and dozens more movements around the country, have all been part of something bigger than the individual projects themselves.

They’re sending a message to the entire country, and even the world. That if we don’t fight any and every disturbance to our environment, the future of our planet will be the one to suffer the consequences.

“One of the analogies I’ve used is there’s this thing called death by 1000 cuts. If Bernheim is celebrating 90 years and we want to be here for 90 more and 900 after that,” Wourms said. “We can’t have little cuts occurring every 10, 20, 50 years it will add up and take the integrity out of our systems.”

Yes, this issue is about a timeline of events, KRS chapters, CPCN applications, and yard signs that sparked a movement. But at its core, Bernheim supporters see it as an instance of corporations disregarding environmental concerns and ignoring attempts to conserve land and its natural features.

But let’s back up. In the beginning, it wasn’t that we actually didn’t care about the environment or protecting Bernheim, we just didn’t fully understand the details of the movement. Rather than taking an active stake in the issue, we passively supported a movement — we silently agreed with efforts to save a forest voiced by those yard signs.

As student journalists, we’ve been told time and time again that the number one element of journalism is the truth. When sources gave us contradicting facts that suddenly skewed our understanding on what was true, it became our responsibility to discern what had happened. Along with finding the information we needed, we also gained an understanding of what real investigative journalism looks like.

The yellow signs are still out there, lining the yards of our everyday commutes. They still display the bold message it had when we first began this story, but the meaning for us has shifted. For us, they not only act as a symbol for movement to counteract corporations’ actions, they now mark the beginning of a call to action. A call to research, a call to investigate, a call to dig a little deeper.

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.