Our City Uncovered

Louisville’s reputation has changed in the last few months. This is the city I know.

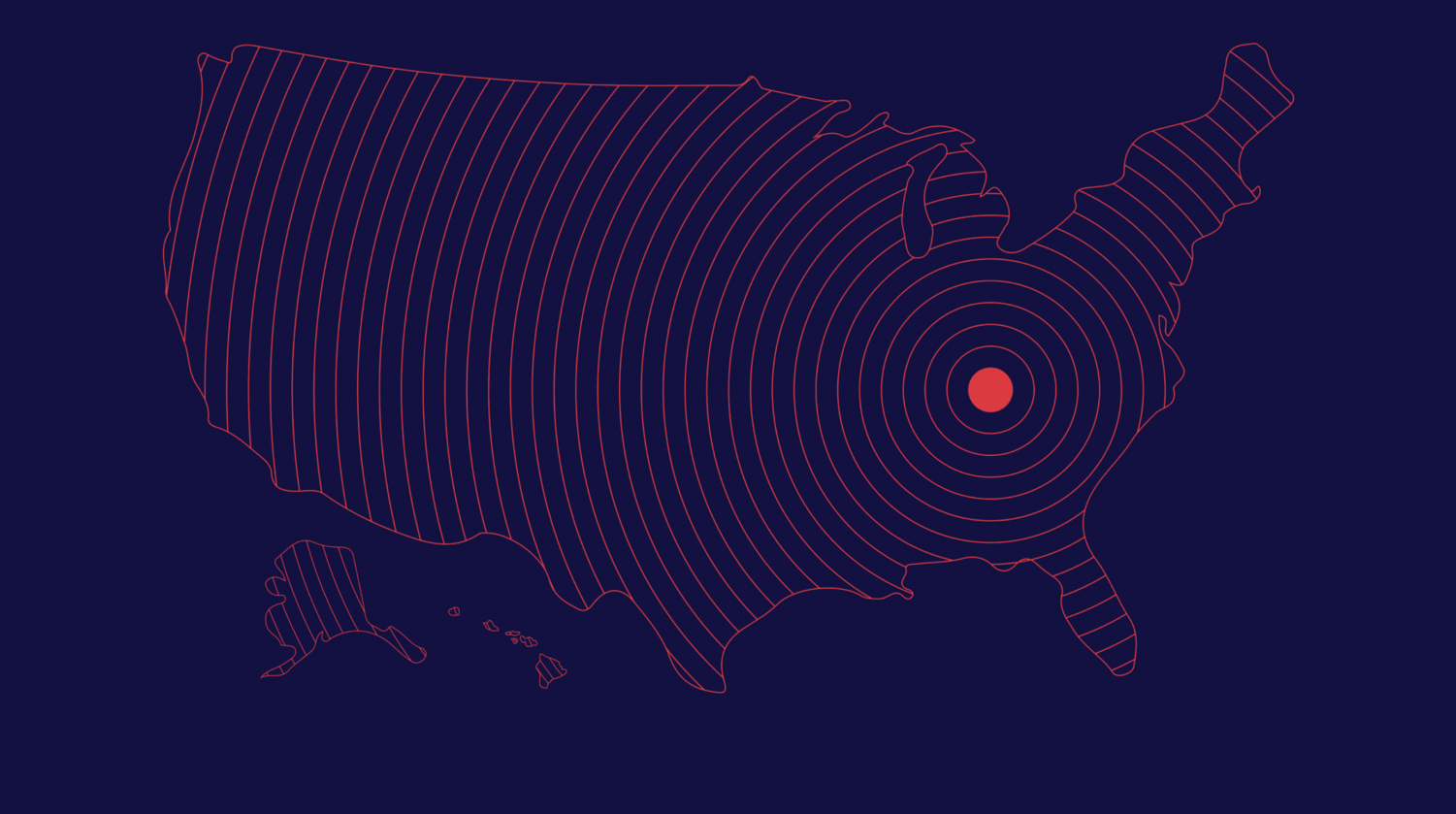

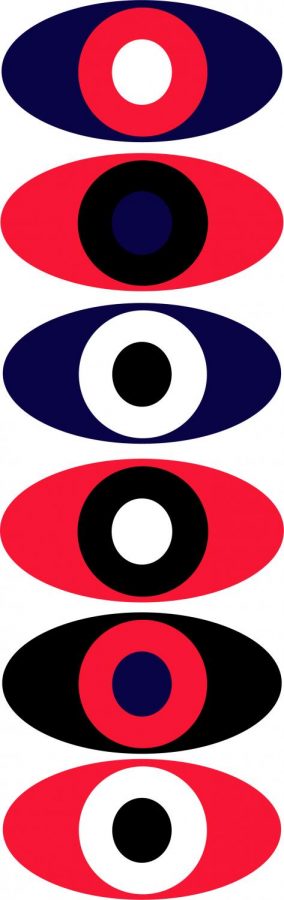

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak within Kentucky, Gov. Andy Beshear has been using the terms “red zone,” “orange zone,” “yellow zone,” and “green zone” to categorize the level of concern for each county. Jefferson County has been in the red zone. Likewise, the other counties are painted in the same color.

The red zone serves as a visual representation of the critical situation in Louisville. Like a stop sign, it commands us to halt — halt because there’s traffic and if we continue like we do, there’ll be a collision.

But how did we get in the red zone in the first place?

We started the year off being praised for having low cases before suddenly skyrocketing to being in the red zone in a matter of months. If you were like me, you were probably scrolling through dozens of Andy Beshear memes at the beginning of quarantine. However, not every Kentuckian is an Andy Beshear fangirl. In fact, we had just crawled out of a neck-to-neck election between former Gov. Matt Bevin and current Gov. Andy Beshear, in which the state of Kentucky swung the pendulum back to blue after being rooted in red in recent years.

Thus, one of Beshear’s first priorities upon entering office was to tackle the growing pandemic. But, this would prove to be difficult considering he never truly won over all the Kentucky Republicans. When Beshear announced a state lock-down, some conservatives had protested against him. When Beshear encouraged — and then mandated — Kentuckians to wear masks, the same occurred. As months in quarantine dragged on, many Kentuckians, conversative and liberal, ceased their duty to wear masks and stay inside. This is what has led to the growing numbers within our Commonwealth.

Now, most of us are scrolling through news updates day after day and trying to keep up with the changing times. It’s become a repetitive cycle that feels like we can’t move forward because our obstacles become even more overbearing by the day.

Similarly, this reflects another underlying problem within our Cardinal city.

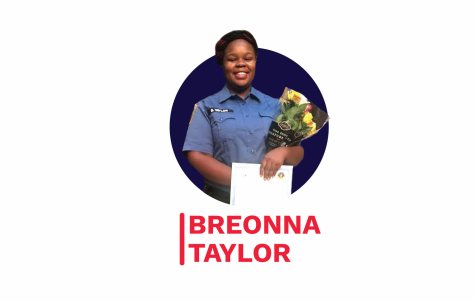

It was March 13, 2020 when a 26-year-old ER technician was shot within the walls of her own home.

Her name was Breonna Taylor.

If you’ve kept up with the news — or live in Louisville — that name is most likely ingrained in your brain.

It’s been over ten months since her death. Eight months since the protests started.

And, in September, the Kentucky grand jury decided to indict only one of the three officers involved in her case for the shots he fired wantonly into neighboring apartments.

Now the nation’s general perception of Louisville, and Kentucky as a whole, has shifted from fried chicken, Derby days, and “hillbillies” to toilet paper wars, Mitch McConnell, and the city that couldn’t give Breonna Taylor justice.

Our quiet city was no longer curtained in the backdrop; we were front and center with the spotlight shining directly on us for the rest of the country to scrutinize.

As someone who was born and raised in Louisville, it was staggering, but very much necessary, for me to witness how our city was transforming. But it was also frustrating being aware of how the rest of the nation falsely perceived us from the beginning. People may recognize us as the state that has the college sports rivalries, mint juleps, and was the birthplace of Muhummad Ali. Although we do wear shoes around here, those don’t even graze the surface to the Louisville that I grew up with.

The Louisville that I know isn’t just the Kentucky Fried Chicken, it’s the small, locally owned restaurants that line up the streets of Bardstown Road.

It isn’t just the horse-racing — which I’ve never done or been to — it’s the dozens of state parks that showcase the lawns and pastures in the north and the rolling hills in the south.

It’s not just the UofL games, it’s the Kentucky State Fair where we would walk out of the Kentucky Exposition Center smelling like cow poop just to end the night on the Ferris wheel.

It’s not just the Derby that we celebrate, but it’s the Backside Learning Center — resting just behind the Churchill Downs race track — that aids Louisville’s immigrant population.

It’s the clutching onto the car handles while driving down Dixie Highway, or as most of us refer to it as, “Dixie Die-way.”

It’s the “Keep Louisville Weird” movement that brings attention to all the small, unique businesses that adorn downtown Louisville.

It’s the aged Victorian homes that also decorate the streets of historic old Louisville.

It’s the Kentuckiana Pride Festival that celebrates the LGBTQ+ population in Louisville, in which Louisville has the 11th highest rate of people who identify as being part of the LGBTQ+ community.

This is the Louisville that I grew up with. It’s the one that I call home.

However, this Bluegrass state isn’t free from criticism, and it should never be. Louisville is weird and beautiful, but also flawed in many ways. The dealing of the Breonna Taylor case emphasizes how far we are from being the Louisville we think we were.

The Louisville I call home needs to be held accountable for its mistakes, and we as Lousivillians need to own up to it.

The Louisville I call home can no longer hide behind its hometown reputation because that’s no longer our only reputation.

And, in the Louisville I call home, we can’t walk down Market Street to admire the mural that claims “Our City, Our Home” when our city doesn’t feel like home for everyone.

Louisville is in the red zone, but we don’t have to stay in the red zone. We don’t have to merge into traffic or even find a way around it; if we unite together, we can cease to have any traffic at all. We can become the city that’s no longer halted in the red zone, but working to move into the green zone where it’s safe for everyone. Louisville is far from that, but we’re working to get there. The protests all over downtown Louisville showcase that, and, most important, the Louisville population showcases it.

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.