Flipping Pages

Little Free Libraries in Louisville bring people together and inspire community involvement.

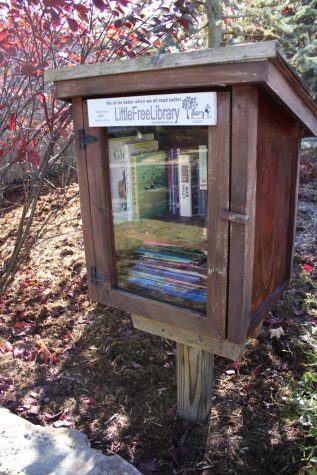

It was a Saturday afternoon. Mary Sullivan walked along the sidewalk, her arms sagging under the weight of the bulky cardboard box she was carrying. She stopped in front of a little wooden structure, her box thudding loudly as she dropped it onto the concrete. Sullivan opened the top flaps, revealing a multicolored array of covers. Books were stacked on top of each other haphazardly, novels and dictionaries mixed with Bibles and fairy tales. Sullivan removed them one by one, placing them neatly onto the little library’s wooden shelves. Once the box was empty, she made her way back down the sidewalk to return it to the trunk of her car. Before she drove off, she looked back to where she came from, smiling at the library that would soon be surrounded by eager readers. Her job was done.

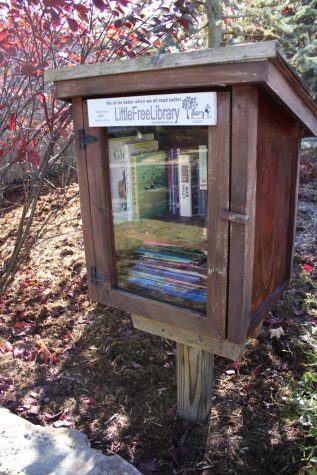

Little Free Library (LFL) is a nonprofit organization based out of St. Paul, Minnesota with libraries all across the country. Their mission is to ensure that every reader has access to books. LFL also serves as an outlet for community outreach, activism, and education.

Each individual library is constructed and maintained purely on a volunteer basis, which embodies the organization’s goal of inspiring people to share their love of reading with others.

Metro United Way (MUW), a nonprofit that promotes volunteer work, became involved with LFL in 2014. Sullivan, former manager of corporate engagement at MUW, spearheaded this involvement after she read online about a man named Todd Bol, who started LFL to honor his mother, a retired teacher and librarian.

“So he made this box, and stuck it in the front yard,” Sullivan said. “And today it’s international.”

A major focus area of MUW in 2014 was early childhood education and kindergarten readiness. After Sullivan came to them with her newly-discovered knowledge of LFL, MUW partnered with the 2015 Leadership Louisville Bingham Fellows Project, which is a leadership program in Louisville aimed at discovering solutions to community issues. In 2014, one of their subject areas was educational programs in west Louisville. This included zip code 40210, which, at the time, held the lowest literacy rate for children attending Jefferson County Public Schools.

“So, I went to my boss and I said, ‘We need to put these libraries in neighborhoods,’” Sullivan said.

After deciding to install libraries in neighborhoods in west Louisville, Sullivan and her team at MUW talked to Glen Kelly, a neighborhood advocate in the 40210 zip code. Kelly challenged them to install 40 libraries in her neighborhood — one for each block. Sullivan and her team told Kelly that if she could get 40 residents or organizations that would give permission for libraries to be installed on their property, MUW would provide them.

“Of course, we had no idea where we were going to get 40 libraries — who was going to build 40 libraries?” Sullivan said. “Unfortunately, she only got 15 people. But 15 was a start.”

As of October, MUW has 42 libraries in west Louisville: 36 of which receive books from the organization, three that receive books from their hosts, and three that are currently out of commission due to vandalism.

Even though she is retired, Sullivan still works with MUW’s libraries as a volunteer, distributing books to their various locations and performing the occasional repair. The fulfillment she gets from working with the libraries is what she says inspires her to continue volunteering.

“Many times we get notes in libraries saying, ‘Do you have this author, that author?’” Sullivan said. “You know, it’s reaffirming. Like when we’re out there putting books in the library, somebody comes by and says, ‘Thank you.’”

In addition to MUW’s libraries, there are many others registered with LFL scattered throughout the community, as well as those that are independently made and owned.

Little libraries live outside of small businesses, organizations, and individuals’ homes. In many ways, they are a means through which people can come together, whether that is by sharing notes with other visitors of the libraries, having group building and painting days, or volunteering with other community members to achieve their goal.

Abby Crady (17) has been involved in her neighborhood’s library since it was built. Her name can be found on the back of the library, surrounded by hand-painted purple, orange, and blue flowers.

Along with her involvement in the construction of the library, Crady remembers it as a prominent fixture in her childhood memories. She would take her friends to visit the library, encouraging them to participate in the “take-a-book, leave-a-book” system. Now that she is older, she sees others making the same memories.

“It’s really cute to see the younger kids that have grown up, because obviously when I was younger, those kids were newborn, but now that they’re older, they take their friends to see it,” Crady said.

Watching her community breathe life into the library has allowed Crady to understand its importance.

“Some people might not see the gravity of a wooden box, but I don’t know. I feel like it is a communal space,” Crady said.

These spaces can take shape anywhere and any person can be the one to initiate them. Crady’s was built from scratch by her and her neighborhood, but LFL sells starter kits for people that want to host libraries of their own. Because of their simple installation, little libraries can be easily repurposed for a variety of community needs. They help where help is needed, such as in MUW’s accessibility project, while also bringing people together, like in Crady’s neighborhood.

The libraries have the ability to enact change wherever they reside, flipping pages for communities as people flip the pages of books.

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.

Kendall Geller is a senior and the Copy Editor for On the Record. This is her third year on staff and she is excited to work with all of the new writers...

Silas is a senior designer for On the Record. This is his third year on staff and is excited to get back to designing spreads. Silas is involved in various...