I live in a house built for four. There are three bedrooms upstairs, yet one always sits unused. My bathroom has two sinks, two towels, two soap dispensers; it’s as if there were two people using it.

But no, I am the only one. Perhaps the distinctions are most prominent at dinner. My family’s kitchen table sits with four chairs evenly situated around its sides. My mom and dad sit facing each other; I sit facing the empty seat. I have looked at the same empty seat, its red cushion looking as new as when it was purchased, for all 16 years of my life. I grew to question this chair. Why did we even bother having it, when there was no one there to use it?

The only time it ever got used was when my grandpa came over for dinner; he would get my seat and I would get shoved into the spare. It is by far the worst seat at the table. Its back rests up against the green wall of my family’s kitchen, blocking it from pulling out all the way, and the constant blow of cold air coming from the vent beside the chair makes the seat increasingly uncomfortable.

If I had a sibling, I am sure we would fight over who would have to sit there. I have heard enough stories from my friends to know that the solution would not come from a simple settlement, but instead a schedule where we would switch which seat we sat in every other day. And an argument would start every once in a while if one of us wasn’t home for dinner. Would the schedule stay the same or would there be a switch up?

This is all just hypothetical because I don’t have a sibling.

My house is a constant reminder of that fact. Maybe it’s because it was built in 1976, at a time when the idea of the two-parent and two-kid family structure swept over the country. Between the years 1975–1979, more Americans said they wanted two kids as compared to any other amount of children. Zero to one child, on the other hand, was the least preferred amount.

Maybe it’s because four is an even number. Four represents symmetry, a life where everything is even. I envied that life. The one where I would always have someone to talk to, someone to spend family vacations with, just someone there, constantly.

While I always yearned for this family, I never put much thought into what living with a sibling truly entailed. I wanted to understand what it meant to have a sibling beyond just hearing snapshot stories my friends told.

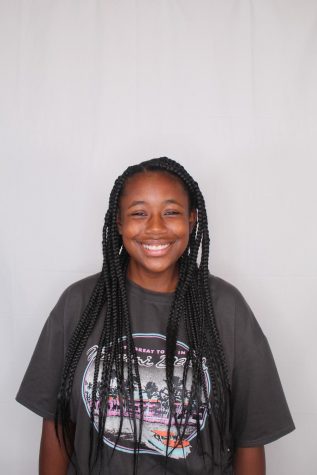

That’s when I came across Weslynn Bonner.

Like myself, all Bonner ever wanted was siblings. She lived with her mother in an apartment complex, surrounded by neighbors whose families were much larger than her own. She envied those who had siblings.

“I remember telling my mom I wanted a little sister. I guess she took it seriously,” Bonner said, now 18 years old.

When Bonner was five, her mom gave birth to her younger sister, Mylynn “MyMy” Alexander (13). Bonner was ecstatic to have someone to play with. Even at her young age, she knew that she would love her sister endlessly.

Her new title, “big sis,” was one she wore proudly, and she didn’t much care that her sibling’s arrival meant that she now had to share her mom with someone else. After years of being an only child, Bonner was just glad to have someone to play with. She and her sister spent a lot of their time together at Shawnee Park, running around the playground and racing down the double red slides.

A few years later, her mom gave birth to Bonner’s youngest sister, Rayleigh “Ray” Shoulders (8).

“I do remember it being a little bit different with my last sister,” Bonner said.

At this point, her family had moved into a small home in the West End. For Bonner, living in a house for the first time was a big shift, and the addition of Ray into the family meant she was now taking on additional chores, like laundry and dishes.

“I learned how to do everything myself, like everything,” Bonner said. “I didn’t want to bother asking my mom because she already had a lot going on.”

As if that wasn’t already a lot for 10-year-old Bonner, she, being the oldest of the three girls, took on a lot of parental responsibilities while her mom wasn’t home.

“I always wanted to just help my mom,” Bonner said.

She would pick Mymy up from the bus stop, make sure she made it home safely, and watch both sisters until her mom got home later in the evening.

I thought back to when I was 10. The era of Justice leggings paired with boots. Of getting that first taste of social media. Of figuring out that boys don’t actually have cooties.

When I was 10, I was still a child. So was Bonner, though she didn’t act like it. She was mature beyond her years, and while her life seems distant compared to mine, it simply felt like a normal routine to her.

“It was just what it was,” Bonner said.

Bonner’s mom was working to get her master’s degree when she gave birth to Ray. She worked hard, managing a job — at times even two — while the girls were at school, and taking classes at Daymar College by night. It wasn’t easy, and definitely less than ideal, but she always made it work.

“She had to get her degree so she could get a better paying job, and she had to work so she could pay for stuff,” Bonner said.

On average, a single mother earns about one-third of the annual salary than that of a dual-income family: $36,000 versus $112,000. In 2016, nearly 4.3 million women in the United States maintained more than one job, many working over 70 hours a week. As a result, it becomes exceedingly difficult for single moms trying to balance work and family life.

“My mom’s biggest thing was that, no matter what, she wanted to make sure we had food on the table and we had the lights on,” Bonner said. “She would never really spend money on herself, but she really put everything into us.”

While Bonner recognized and was always grateful for how much her mom did for her and her siblings, the responsibility of watching over them was overwhelming at times.

“It was a lot. She wasn’t really home that much,” Bonner said.

This scenario is known as parentification: when the line between the role of a parent and that of a child is blurred. Parentification takes on many forms, some more severe than others. Bonner experienced what is known as sibling-focused parentification, which involves one child taking care of another.

When those expected to care for younger siblings are still children themselves, the responsibility can be hard to deal with. Bonner was only 10 years old when she began looking after her siblings. And granted, for a short while, they had a babysitter, but that wasn’t always consistent. While her friends were busy picking up new hobbies and interests, she was at home helping her siblings.

“I do remember having a weight on my shoulder, you know, I gotta make sure my sister’s okay,” Bonner said.

Bonner handled responsibilities at home that many children will never have to experience. Spending so much time taking care of her younger siblings meant less time to do the things she enjoyed.

“I did miss out on some things. Like going to the mall or the movies,” Bonner said.

One day, Bonner, who had just recently gotten home, sat on the couch in her family’s living room. Her eyes were glued to the television, as flashes of a green field, ball, and women kicking moved across the screen. She followed the same ritual of watching professional women’s soccer before each of her own games, and this afternoon was no different. It was her team’s rival game, the one they had been anticipating all week and practicing for all season. Bonner felt every emotion: scared, anxious, excited. Her mom was on the phone in the other room, but she didn’t pay much attention to it. That was, until her mom walked into the room, pausing in front of Bonner. She let out a short sigh before saying that she got called into work.

Bonner knew what this meant. She would have to stay home and watch her siblings that night. She would not make it to her soccer game.

“I was mad. I was heated. I was upset,” Bonner said, reflecting on this day. “Everyone on the soccer team was calling like ‘oh where are you, where are you, where are you?’ And I was like ‘I can’t go, I gotta babysit.’”

Though Bonner was mad at the moment, she knew that her sisters came first. She would do anything for them, even if it meant missing out on opportunities and holding onto the pressure of watching over them. Quality relationships between siblings reduce the negative effects present in parentification and there is no uncertainty that Bonner’s relationship with her sisters is one she cherishes.

When Bonner started her freshman year of high school she moved in with her dad. There wasn’t really a specific reason other than the fact that he offered — and she wanted — a change of pace. She went from being the oldest sibling at her mom’s house to the youngest at her dad’s. Her siblings there would tiptoe around her, always bringing up and joking about her age. She didn’t feel valued the same way she did at her mom’s house.

Ten months later, she moved back in with her mom, and while she wasn’t there for very long, it changed how she viewed her siblings and her role as “big sis.”

“After that period, I always put in extra work to try and be a better bigger sister,” Bonner said. “I’m never going to let my sisters feel like that, ever.”

Beyond her newly changed perspective of her siblings, living with her dad showed Bonner just how much she appreciated living at her mom’s house.

At her mom’s house creativity was appreciated. Freedom to explore different interests is something that Bonner cares a lot about. When she was 11, she started a business of her own selling and trading lip balms online. Her platform grew and she began spending a lot of time sending packages out to customers. Her sisters watched Bonner’s every move, and they, especially Mymy, greatly looked up to her work ethic.

Bonner wants her sisters to learn the importance of pursuing things they are passionate about. She doesn’t care exactly what that thing is, as long as they are eager to stick to it.

This characteristic of Bonner, the one where she is thinking of the successes of her sisters in the future, is where the real effects of parentification take form. She is a role model for her younger siblings in every sense of the word.

As an only child, I never had someone like Bonner to look to for help. Yes, I had my parents, but I didn’t have someone my age to truly connect with. In many ways, that is the worst part about not having a sibling.

Apart from that, Bonner’s siblings are people that she knows she can count on, and her relationship with them is stronger now than she ever imagined possible.

“All the effort I put in early on to be a good big sister paid off, because now they’re my life-long best friends,” Bonner said.

Sibling. A single word. Seven letters strung together; its two syllables mean so much. It once was something I wish I had. I still wonder what my life would look like if I had a sibling. Maybe I would stand up for myself more or be able to show more empathy. But, I now know that what I don’t have may be my biggest reward. What I don’t have is the responsibility to watch over another human being. What I don’t have to face is missing practices and events because I had no one home to take me. Those are privileges that I never accounted for earlier.

Maybe the world was built for a family of four, but it was built for a family with a steady income, a family who had access to consistent after-school care, a family that has enough support to truly raise those kids. Sadly, for Bonner’s family and many others around the country, that is not the reality.

For a long time, I thought something in my life was missing. It was evident in the empty chair I looked at during family dinners or the leftover game piece that sat untouched in the cardboard game box.

I will never get to experience the kind of friendship that Bonner has with her siblings. The kind of friendship that will always be there, whether I like it or not. The kind of friendship that results in spontaneous midnight meetups in the kitchen, or sharing an eye roll over our parent’s comments.

Though, my family is not incomplete.

Being an only child is not wrong. Being a single mother is not wrong. Living in a family with six, seven, ten siblings is not wrong. Our family dynamics define our upbringing, they make us who we are. One person’s experience is not “better” than another — it’s all relative.

For me, my house built for four can also faultlessly fit my family made of three.