Walk with purpose. When is the sun setting? Stay away from that alley. Was that a shadow? Look over your shoulder.

Any time I’ve been alone and out of the house, regardless of when or where, these thoughts have rushed through my mind on a constant loop while my head has remained on a swivel. They are second nature, but I wish they weren’t. I wish that in response to a string of brutal robberies and assaults of women in southwest Louisville in late August, the Louisville Metro Police Department’s (LMPD) solution wasn’t to simply be vigilant. To travel in numbers. To eliminate distractions such as cell phones. I wish that I was startled by the fact that a woman had been followed home only two miles from my house. Instead, I felt numb.

Women feeling unsafe in Louisville should be an anomaly, but many girls have felt the need to equip themselves with pepper spray, self-defense keychains, and in cases like mine, a swiveling head from a young age. But where do we draw the line between caution and losing our personal freedom? Why is the solution in our hands and not those of the offenders?

It is time to change the conversation. Women and girls across Louisville have found safety in each other, coming together to foster a balance of both physical and mental empowerment. With strength in numbers, girls in Louisville are flipping the narrative.

Or, in some cases, getting flipped ourselves.

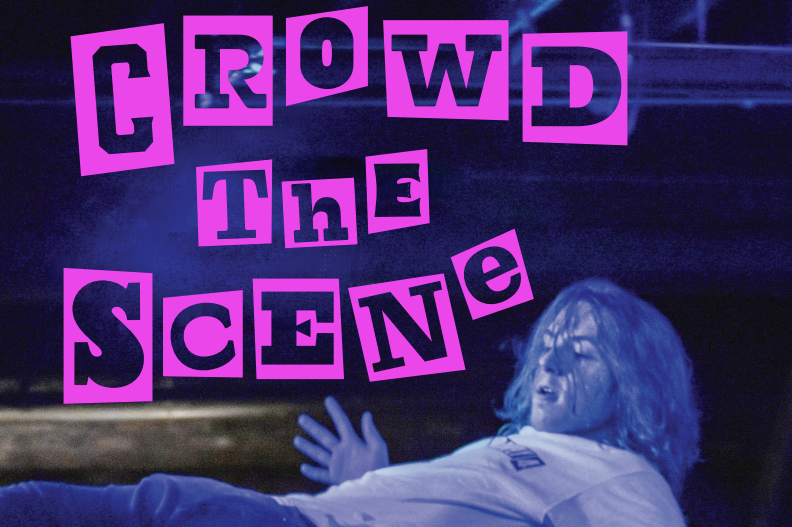

Laying flat on the floor, I wrapped my feet around my attacker’s back, squeezing my arm around their neck while using the other to block their attempted punches. I struggled to keep up with their expertise and speed, employing each defense tactic as quickly as I could recall it. When the attacker finally stood up, I locked my feet against their hips, distancing their punches. Soon enough, I let go, slamming them back down to the floor where I resumed wrapping my feet around them. I tightened my arm, ending the altercation.

Then we high-fived.

- • •

Gracie Jiu-Jitsu, a brand of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, is a self-defense martial art and combative sport. In Kentucky, Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Louisville is the only training center of its kind that is certified by Gracie University, the overarching organization that directs Gracie Jiu-Jitsu education across the country. There, a group of instructors teach a variety of self-defense classes, ranging from Bullyproof, a class for young children, to Women Empowered, a class specifically focused on women’s self-defense. I attended Women Empowered on Nov. 6.

Earlier that day, Leeann Manganello, Women Empowered instructor and my soon-to-be “attacker,” walked me around the dojo in preparation for my shadowing, which would take place later that evening. There, I watched as her husband, Allan Manganello, the founder and head instructor at Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Louisville, coached a handful of men on the blue mat that extended across the entire room. I took note of everything I saw, eager to observe more later that night, but they were not going to let me simply stand back and watch. Regardless of the journalistic motivation behind my attendance, they insisted that rather than write about what I see, I write about what I do.

When I came back that evening, Allan and Leeann made good on their promise. The class wasn’t just a viewing, but rather an immersion into the core principles of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu and the culture enforced at their branch in Louisville.

At the beginning of the class, I sat down with Allan and the group of first-time attendees as he explained the importance of not only physical preparedness, but mental preparedness. There was a sense of urgency present throughout the entire conversation. He explained that most of the time, attacks on women are at the hands of someone they know rather than a “ski mask stranger.” With this in mind, he said, it was important for women to set boundaries in their relationships with others.

“No one has the right to touch you without your permission,” Allan said.

Enforcing this assertion and setting boundaries were where Gracie Jiu-Jitsu came in. Allan and Leeann described Jiu-Jitsu as a superpower: something others can’t do that gives you a leg up. To employ this superpower, it is necessary to approach it as a means of escape rather than one of fighting. In this way, Gracie Jiu-Jitsu could be used to tire your opponent, maintain your energy, and, in the best situations, escape the scene.

The skill that I learned that afternoon was a punch block series. To practice with a real life opponent, students paired up and took turns being the “attacker.” However, the attacker was far from a bad guy. Instead, their role was to place a student in a realistic situation while also supporting them. Leeann, as well as the other attackers, coached their student through the moves and encouraged them during the fight. Still, the attackers were not expected to go easy on their opponents. In fact, Leeann emphasized that if your attacker was being too nice, you should taunt them and say, “My grandma hits harder than you.”

The supportive environment of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Louisville is what defines its culture, and it was present the entire time I was there. Even when Leeann and Allan were demonstrating moves, there existed a balance between necessity and fun, with most of the demonstrations ending in smiles and laughter. It was for this reason that I walked off the mat not only empowered by my progress in physical preparation, but in my understanding of the importance of a strong mindset. This shift in mentality was far from rare.

In fact, it occurred in Lena Mannarelli, 19, a freshman at Bradley University. Mannarelli started training in the Women Empowered program with her mom and sister when she was 14 years old at the encouragement of her aunt, an instructor at Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Louisville. A year and a half after joining the program, Mannarelli submitted a tape of her techniques to the Gracie University headquarters for review to earn her pink belt, showing her completion of Women Empowered. Manarelli’s aunt pointed out that young girls looked up to her achievement, which inspired her to continue her training and pursue instructor certification.

“Actually seeing how I affected other people’s confidence, that just made my day,” Mannarelli said.

After endless hours of hard work, she became the youngest certified Women Empowered instructor at 17 years old. But before training and eventually becoming certified, Mannarelli was a timid person.

“It’s not just that, ‘Oh, here’s moves to make you feel safe,’ but it overall brought up my mental confidence,” Mannarelli said.

In fact, Mannarelli thought that if she hadn’t joined when she was 14, she wouldn’t have been able to enter college with such confidence. After watching the infectious surety of the instructors translate into newcomers, including myself, I had no doubt that many other members shared her experience.

In addition, Mannarelli learned from the empathy with which Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Louisville approached assault, being mindful of all experiences and possible triggers.

“Be more supportive of other people that you hear,” she said.

But how can we best support other people? How do we approach the subject of violence with consideration and sensitivity?

Hannah Nussbaum, program coordinator at the University of Louisville’s (UofL) Prevention Education and Advocacy on Campus and in the Community (PEACC) Center, said that it is what we do after we listen that matters.

UofL’s PEACC Center provides a safe place for students who have experiences with violence of any type. Nussbaum focuses on teaching students how to take action when violence occurs.

“It’s what can you as an individual do in an instance of violence to alleviate that violence,” Nussbaum said.

However, to be able to approach a violent situation, it’s crucial that bystanders be conscious of their strengths and weaknesses. This allows bystanders to intercede in a way that is safe for themselves and others.

“Let’s look at what works for you,” Nussbaum said. “What is your skillset?”

While prevention and advocacy look different from person to person, PEACC brings people together with a shared interest: safety. It does this by offering a combination of small-group activities, from trauma-informed yoga groups to sushi-making nights, as well as large scale events. One of these large scale events was PEACC’s annual Take Back the Night march — the oldest global movement dedicated to advocating for women’s safety against sexual violence. Although PEACC stopped hosting the event at UofL after COVID-19, Take Back the Night’s influence has extended across the world since its formation in the 1970s. Nussbaum, who organized the event for eight years, approached it with the same sense of care, caution, and urgency as Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Louisville approaches their teaching, making sure to act as trauma informed as possible.

Through her teaching, Nussbaum emphasized the importance of community support.

“You are 100 percent not alone,” Nussbaum said. “There are people who will listen to you.”

Louisville’s younger generation has the opportunity to break the stigma around violence simply by not being afraid to speak about it.

“A lot of people, younger people, today are willing to see things very out of the box,” Nussbaum said.

Members of Girl Up Prospect are doing just that.

Girl Up is an internationally recognized, youth-centered organization working to empower young girls with leadership and communication skills in the fight for gender equity and justice. The program has 6,500 clubs across 152 countries that carry out its mission.

Girl Up Prospect, based out of North Oldham High School (NOHS), is one of five high school branches in Louisville. It’s the largest club at NOHS with 120 total members and 70-80 consistent meeting attendees. They are often forced to limit attendance at their biweekly meetings sheerly due to seating availability. At each of their meetings, they address the complexity of girlhood, analyzing the unwritten social norms placed on girls. They do so by balancing discussion with community-building activities, such as the “Make Your Own Tote Bag” fundraiser they hosted in October. But some members said that the club was more than conversation and crafting — it was a safe haven.

“We’re all in Girl Up for one thing, and it’s to support each other and lift each other up,” said Mara Passmore, 17, senior at NOHS and secretary of Girl Up Prospect.

Girl Up Prospect serves as a place for girls to come together and bond over their shared lived experiences. It is not a place for girls to tear each other down, but rather find common ground. As the societal pressures placed against women, regarding both safety and unaddressed stigmas, grow, it is increasingly crucial that girls have a place to find strength in each other. Girl Up makes this possible.

“Whoever you are, whoever you want to be, you are welcome here. We love you, we want you, and we will keep you safe in this environment,” Passmore said.

The members of Girl Up Prospect approach the idea of safety with an emphasis on mental empowerment. The foundation of the club is based on inviting anyone and everyone to join a community and belong. By doing so, the club works against the harmful norms of society that cause feelings of unsafety in women.

“We shouldn’t have to know how to defend ourselves in order to be safe. We should be safe regardless,” said Josie York, 17, senior at NOHS and president of Girl Up Prospect.

So how do we put an end to this seemingly endless cycle?

“We are facing these challenges and we are facing these obstacles in life together,” York said.

As a unified force, girls and women have the power to create change. We can do this by establishing boundaries and learning how to enforce them — on or off the mat. While physical preparation can add a level of comfort to unsafe situations, it is the confident and empowered mindset developed from collaboration with other women which holds immeasurable value.

It is time to bring safety into the conversation, and more importantly, listen to other people who do the same. As youth, we have the power to determine the culture of communication with which we approach safety and empowerment. It is a woman’s world, so let’s fight for it. •

- Writing: Syd Webb

- Design: Silas Mays

- Photos: Sadie Eichenberger