I felt my skin crawling — the type of crawling that only occurs when a conversation is painful to escape. At the 2024 Golden Globes, host Jo Koy faced waves of criticism for his description of “Barbie” — a movie that analyzed the female experience and empowered women. His monologue included sexualizations of the movie, ultimately developing his takeaway that Barbie is based on “a plastic doll with big boobies.” I cringed in response, and I was not alone in my reaction. Director Greta Gerwig’s expression was one of disappointment, and co-stars Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling looked embarrassed and slightly nauseated.

As I attempted to pull my gaze away from the trainwreck that was Koy’s performance, I could only wonder how upsets like his occur. While it remains unknown how writers allowed Koy’s jokes to make the public stage, it is explainable as to why he was not met with laughter. The root of his problem lies in disparagement humor, a form of comedy based on degrading another person or social group.

Disparagement humor is only effective because it holds two messages: one explicit and one implicit. The explicit message is offending its target, but the implicit, lighthearted context of comedy counteracts its potentially negative effects. At the Golden Globes, Koy’s explicit message outweighed the implicit, but oftentimes, disparagement humor succeeds without criticism. In these cases, our laughter has the power to justify derogatory humor, perpetuating an endless cycle of prejudice. Whether it is laughing at a performance or just joking with a friend, we love to laugh — just as long as it is not about us.

So where do we draw the line between comedy and cruelty? As comedy culture changes as a whole, the answer may be found in the comedy style of “punching up.” While widely debated across critics and comedians, punching up is the concept of the “weak” joking about the “strong.” This form of humor ensures that the privileged and powerful don’t use comedy to disguise preying on those of less societal stature. But how often are comedians actually punching up? And more importantly, what happens when they don’t?

Drop the Mic

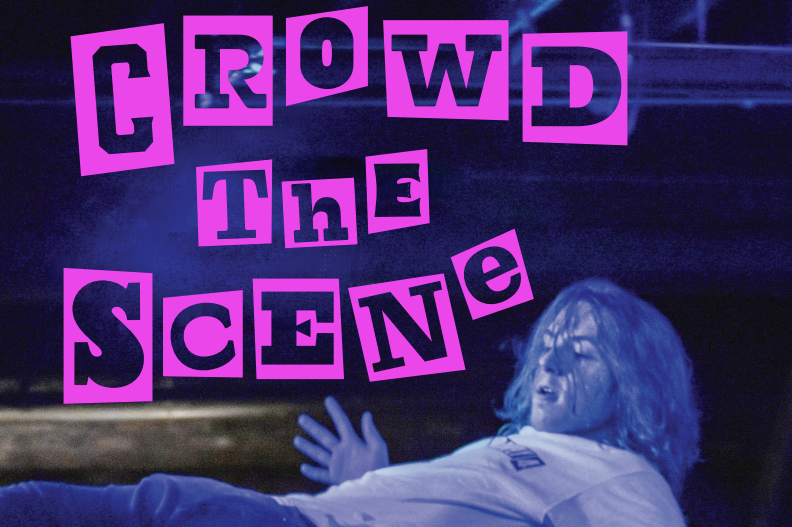

To answer this question, I turned to a smaller scale with less awards and more brick walls: the Louisville comedy scene. Here, big names enjoy our bustling city while locals find comfort in the familiar. Various venues, such as Louisville Comedy Club (LCC) and The Caravan Comedy Club, host a mix of famous acts and open mic nights. There, new comedians can work on stepping out of their comfort zone, developing a new hobby, or trying out fresh material. Because of this, their jokes immerse the audience in the comedic spectrum.

When I attended shows at both LCC and The Caravan in February, this spectrum came to life. Couples in their 20s could laugh alongside ones in their 60s while comics joked about everything from Lizzo to menopause. There is something for everyone and some things that aren’t for anyone, and as the co-owner of The Caravan Comedy Club, Diannea Comstock has seen it all.

After working there over 20 years ago during college, Comstock is no stranger to comedy culture, knowing all the local headliners, openers, and features. Following a 17-year interlude working at the International Business Machines Corporation, she returned to buy The Caravan with her husband when previous management flaws threatened to shut down the business permanently.

Comstock has watched comedians blossom, fail, and fall somewhere in between. However, she attributes their success, or lack thereof, less to comedians’ personalities and more so, to how they are able to portray their trains of thought.

“They have a thought process going in their head of where they’re going with it even if they haven’t made it to the finish line appropriately yet,” Comstock said.

It is when comics struggle with this tunnel vision — especially those that pursue controversial stage characters — that they can become immune to the harmful effects of their comedy.

“If you’re saying comments that you think are funny and you’re the only one laughing, then it’s not funny,” Comstock said.

Therefore, to combat the possible negative effects of comedy, many Louisville comics are making conscious efforts to avoid disparagement humor. Two of these comedians are Brandi Norton and Jake Hovis — comics that I had the pleasure of watching at an open mic night at The Caravan. The key for them lies in the topics that they most like to joke about.

“I don’t want the victim to be anybody that doesn’t deserve it,” Hovis said. “So most of my jokes are at my own expense, so I’m purposefully self-deprecating.”

And it’s true! His act contained jokes mostly about him, his dog, his wife, and other funny quirks of his day-to-day life. Hovis’s route of self-depreciative comedy is a common practice, but comedy doesn’t have to be solely about the speaker to remain socially conscious. Norton is a prime example of this. Her strategy is to simply be present with the audience and talk about anything — literally.

“I like to work with what’s already been established for sure,” Norton said.

That night, her improv bounced off topics already discussed in previous acts, audience members, and even a heckler in the back. It was fascinating to watch her direct jokes at others while not passing into aggression.

“You can make fun of someone and it be mean, but you can also just make something fun,” Norton said.

One way Norton did this was by involving the oldest audience member in her jokes. An elderly woman in the front row had been laughed at by other comics as she struggled to understand some jokes relating to pop culture. Rather than continuing the trend, Norton chose to make jokes from the lady’s perspective while keeping a silly demeanor to include her. The smile on the woman’s face was visible from across the room while she laughed at jokes that she could relate to without being the butt of them.

Norton and Hovis are a beacon of hope for the comedy community, but there is still work to be done. In fact, most of the work may need to happen off stage.

Off the Stage

Oftentimes, we — the regular Joes — manipulate comedy as an outlet for our grievances. Apart from misunderstanding the effects of comedy, there exists a manipulation of comedy as a disguise for biases and microaggressions.

“There’s a difference in being funny and being hateful, and that’s your fine line,” Comstock said.

But what happens when this line is crossed? On the stage, a bad joke could lead to a silent, offended crowd. But off of it, the effects of harmful comedy are all the more real. It often stems from how we approach problems at a young age. This can be seen in a common response to a young boy teasing a young girl: “If he is teasing you, he must like you.” Seems harmless at the time, but responses like this support the idea that humor can evade social norms.

As we grow up, this idea can manifest itself and have detrimental effects. According to research performed by Dr. Monica Romero-Sanchez, a social psychologist at the University of Granada in Spain, exposure to sexist humor can create an environment that fosters sexual aggression toward women. In her study, men exposed to this form of derogatory humor noted an increase in their self-identified rape proclivity while the men exposed to neutral humor did not. But these environments are not limited to observations made in a study, they are a part of our everyday lives, blending into popular media.

In his Netflix special, “Natural Selection,” comedian Matt Rife jokes about a waitress he had encountered who had a black eye. While joking that management should have kept her in the kitchen, he ends with the punchline that “maybe if she could cook, she wouldn’t have that black eye.”

Jokes like this normalize the abnormal, alleviating the impact of harmful comments in the name of comedy.

However, while it is easy to point fingers, the cause of our society’s growing extremism can be found in ourselves. It is in our human nature to be drawn to likeminded people with similar views. It is why we find ourselves laughing at late night shows and comedy skits skewed in our respective political directions, and it is why we are frequently apprehensive to explore humor from the other side.

But what if the situation was flipped and the spotlight was on us? While we may not be offending social groups on as large a scale as the Golden Globes, our jokes still carry weight as both a teller of a joke and as a member of the audience.

So yes, comedy can be used for negativity, but it can also be used for positivity.

In fact, laughter has been proven to release endorphins, reduce stress, and even boost our immune system. However, as comedian and former talk show host Trevor Noah said on “The Daily Show,” “Just because something is a joke doesn’t mean it can’t be something else as well,” so it is crucial that we evaluate the nuances within our comedy to ensure the benefits humor has to offer.

Because at the end of the day, comedy is subjective. Different comics are meant for different audiences, and for some, it can take an entire career to find the right fit. However, as comics and audiences walk the tightrope between just enough and too much, it is remembering why we enjoy comedy in the first place that can help us make it a community for everyone.