Continuities withstood on each street — small, white houses, a convenience store, a family owned laundromat, and a church. A woman walked with two young children, an older man laughed through a conversation with a passerby, and rowdy teens played baseball in their front yards.

This is Louisville’s West End, an area full of rich culture and a tight-knit community. Because of this, the other implications surrounding western Louisville may be invisible to outsiders; however, many of the citizens’ lack of access to services and opportunities affects their lives every day — especially the shortage of grocery stores and healthy food.

West Louisville houses about 60,000 residents. Despite this, full size grocery stores are hard to come by. There are only two Kroger locations to support the West End’s nine neighborhoods, one on West Broadway and the other off N 35th Street.

On the flip side, grocery stores in the East End are abundant and growing in number. In January, a new grocery store, Publix, opened its first Kentucky location in the East End and not long before its opening, Kroger announced that they were planning on opening a location just across the street. In this area on the eastern edge of Louisville, there are already many grocery stores, including a Costco Wholesale, an in-development project of The Fresh Market, Meijer, Walmart, Aldi, and two other Krogers. All of these options are within three miles of each other, yet they continue to expand while those in the West End lack this variety.

In addition to less grocery stores, many residents don’t have the transportation needed to make trips to the farther locations. According to the Greater Louisville Project, more than two-thirds of Louisville’s residents without a vehicle live over a mile from a grocery store. This means some people only have access to the dollar stores, gas stations, and food marts that are within walking distance of their homes.

Since city and other public funding isn’t able to fully mitigate this issue, a group of high school students are working to transform the narrative — one meal and stop at a time.

Grub on Wheels

Students in a partnership between Waggener High School and Southern High School are aiming to mitigate food apartheid in Louisville. Food apartheid is a lack of access to fresh, healthy food due to societal inequalities within the food system, including but not limited to race, geography, and class. This can have detrimental effects on a community.

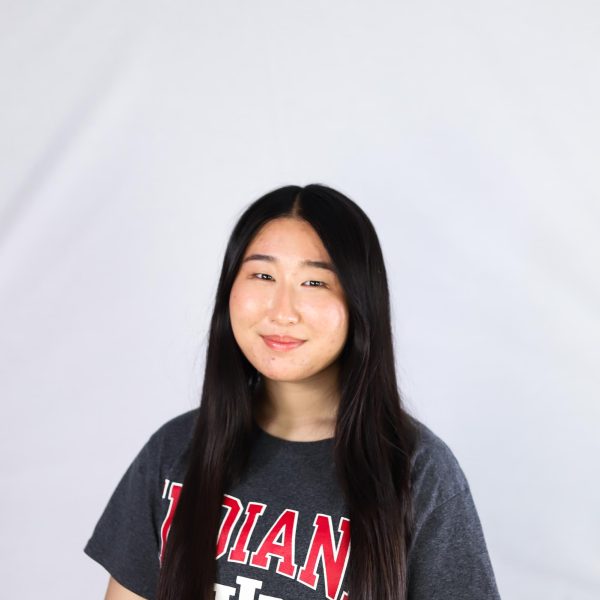

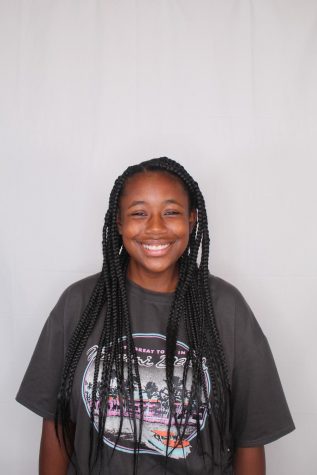

“Inadequate access to healthy food can lead neighborhoods to develop higher rates of illness such as diabetes, heart disease, and even asthma, costing communities millions of dollars in extra health care expenses,” said one Waggener student in a February presentation.

The students at Waggener and Southern are constructing a program called Grub on Wheels which will deliver fresh produce and meals to individuals in the West End. To do so, they are renovating a bus called the Justice Express. Meal delivery routes will be constructed through a geographic information system (GIS), which is a computer system that combines geographic and locational data into a map.

Grub on Wheels is just one of the many projects to come out of the JCPS program, Justice Now.

Justice Now began in January 2021 and allows elementary through high school students to advocate for social change within Louisville. The mission of Justice Now is to empower students to become innovators and community leaders.

“It is all about the idea that a small group of citizens can change the world,” said Matthew Kaufmann, co-founder of Justice Now.

Students create cohorts that address specific issues or inequalities that are not getting a big enough spotlight.

“They become experts, researchers,” said Kaufmann. “It’s all about action research.”

The students then work to directly address their chosen topic by creating a project-based solution that mitigates the impacts of their issue. After this, students have the opportunity to attend Justice Fest, an annual event where cohorts present their project to a group of panelists made up of representatives from different businesses, organizations, and nonprofits around Louisville.

Students identify their issue and explain their research, the phases they are in, and what further funding they need. The presentations are a way to gain funding and community support for their projects. Panelists also give the students feedback and future ideas to further their work.

The goal of these projects and presentations is to allow students to be the drivers of change. Currently, many students are not given opportunities to use their voices, as adults are mainly the ones to take charge in issues that pertain to youth.

“We always talk about students being leaders in the future, but students can be leaders, they are leaders right now,” Kaufmann said. “This is trying to flip that script.”

Justice Fest 2024

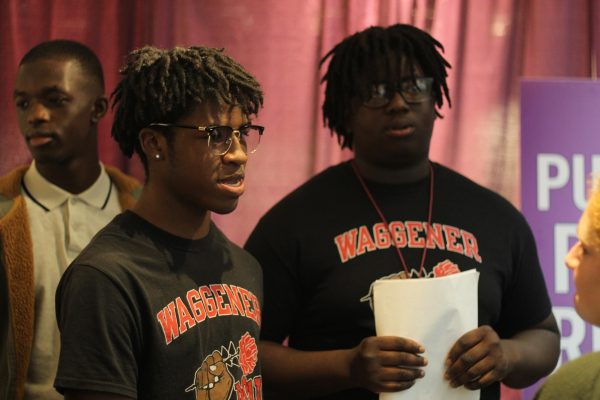

The oak-stained walls of the Muhammad Ali Center surrounded the conference room. Towering over the room, a large screen hung, projecting a text-filled slideshow presentation. Within a few minutes, the empty conference room filled with people. A group of students walked toward the front of the room holding crumpled scripts and decks of flashcards. Sitting in front of them, a series of panelists sat at a long table and held blue and black gel pens, looking up at the presentation screen.

Stepping forward, one of the students took the microphone out of the stand.

“Hi, my name is Shalom and I’m a senior at Southern High School,” the student said, bringing the microphone toward his face. With this, the presentation began.

The students explained the implications of a lack of grocery stores and food security in the West End, as well as details on Grub on Wheels.

“We plan on having our bus stop in the areas that are food insecure and have limited transportation access,” said a Waggener student. “We would love to have all of our items free of charge.”

For the next eight minutes, the students channeled all of their passion and hard work into the presentation, smiling and making eye contact with the crowd.

“Thank you, and now we’ll take questions,” the final student said, ending the presentation. The mic was then passed to the panelists.

“We want to give a donation of $5,000 to the project to assist you with whatever you need,” said Jessica Sharp, manager of Louisville Kroger Division of Corporate Affairs.

The mic moved to the next panelist, continuing the array of responses to the students’ presentation for the students.

“I’ll also commit for our team, volunteer hours and support in getting those donations,” said Shauntrice Martin, founder of Feed the West, a food delivery program where those in need can request groceries, including fresh organic produce.

Donations and support from these panelists provide an opportunity for students to continue their work and outreach. These presentations from Justice Fest allow them to make waves in the community.

Southern students originally pitched the Justice Express at Justice Fest in 2022, where they received a JCPS school bus to renovate. Later in 2023, Waggener’s Black Student Union joined the effort, garnering a large sum of money.

“Last year, Waggener received donations totaling $30,500 to help with our project,” said Jeremy Doe, 16, a junior at Waggener.

With the bus and donations, the two student groups were able to merge and work together on the Grub on Wheels program.

Projects of All Shapes and Sizes

In addition to the bus, Jaswanph Doraigh, 14, a freshman and member of Justice Now at Waggener, is programming an app to make the delivery service more accessible to those with physical or mental disabilities. Doraigh is using the programming language Python to create the app, which will allow users to order produce or meals virtually.

“It’s like a mobile grocery store,” Doraigh said.

While the program is a response to food apartheid and insecurity in Louisville, its creation isa result of the students’ passion. They are eager to shine a light on the injustices within the community and use their voices for positive change.

“I just want to help people,” said DJ Burnett, 17, a senior at Waggener. “I want to make changes for the future.”

Many of the students at both Waggener and Southern also see the impacts of food apartheid on the West End firsthand, bringing them closer to the subject.

“A lot of our students live in the West End and it affects them,” said Laura Motley, the advisor of Waggener’s BSU. “This is something they are going through everyday.”

These efforts from students at Waggener and Southern are part of a larger movement to push students to become changemakers.

Other schools’ Justice Now cohorts have also had direct impacts on the community, from when Justice Now was founded during COVID-19, to present day. These actions were done through different mediums, one in particular focused on the arts by putting students on center stage.

In their cohort, students at Mary V. Moore High School created a play that documented protests in Louisville over time. The students created a script that compared protests from the Civil Rights Movement with those regarding police brutality in 2020. This play was then produced at Actors Theater in Louisville, where kids of all ages were able to learn more about the history of justice and protests within the city. In addition to the students from Moore, students from schools such as Ballard High School, W.E.B. DuBois Academy, and Western High School acted in and helped produce the play.

“It was a phenomenal thing,” Kaufmann said. “It was a big dream to come from an idea.”

Barriers Against Student Voice

Despite the efforts from the cohorts within Justice Now to create change in the community, there are legislative barriers that may prevent them from continuing.

In January, a new Senate Bill, SB93, was proposed to the Kentucky Senate. This bill would prohibit organizations from discussing or using language regarding trauma, race, color, sex, or religion.

“It would get rid of BSU, Justice Now, anything of political nature,” said NyRee Clayton-Taylor, co-founder of Justice Now.

In addition to the effects on Justice Now, SB93 would significantly impact many public school students in Kentucky.

“It will affect marginalized students, all students,” Clayton-Taylor said.

The bill died in the Education Committee in the Kentucky Senate on January 11. Still, SB93 was just one way in which Kentucky legislators have tried to prohibit support and external resources for individuals on the basis of religion, race, sex, or national origin, known as diversity, equity, and inclusion. These are known as DEI programs.

“It would just stifle belonging of students of color, marginalized students,” said Clayton-Taylor. “It is not just black students, it’s white students who have trauma, it’s all students.”

Even though SB93 died before impacting student voices, other bills have been introduced that may jeopardize the individual cohorts of Justice Now and other clubs that are considered “political.”

SB150, a discriminatory bill that targets LGBTQ youth, has substantial impacts on student voice and Justice Now. This bill passed in the Senate and aims to prohibit conversations about LGBTQ subjects, as well as preventing queer students from receiving mental and physical health assistance. Because of SB93, Justice Now students will eventually not be allowed to focus on or mention queer topics.

“If students want to do anything that talks about LGBTQ plus youth, they wouldn’t be able to do it because of Senate Bill 150,” said Clayton-Taylor.

Another bill, SB138, also jeopardizes student expression. Passed in 2022, SB138 governs how schools, teachers, and parents manage the content concerning race and U.S. history. The bill specifically states that schools and teachers are prohibited from instruction regarding academic concept of critical race theory, which follows the idea that race is a social construct and is something that is embedded into policies and our legal systems. SB138 also allows parents to prohibit any lessons regarding critical race theory to be presented to their students. If any student were to express their opinion or base a project on race, SB138 threatens their voices from being heard.

“If a parent feels like they don’t want their students to learn anything that regards race within Justice Now projects, that could upend Justice Now,” Clayton-Taylor said.

Justice Now is taking action against these bills, mainly through outreach.

“We are working together by writing letters and attending protests,” Motley said. “We are well aware.”

For many students K-12, Justice Now is a way to express themselves and their voices. Student projects such as the Grub on Wheels program, are how students are able to make change happen. Currently, Grub on Wheels is still in process, but the students are continuing to renovate the bus and build the app, and hope to have the program up and running by summer.

However, with the possible integration of discriminatory bills, students at schools like Waggener and Southern would be robbed of an opportunity to make change in their community. Youth voice is extremely valuable because the issues around us will one day, in the near future, be ours to tackle – we will be the policy makers, the voters, and the community leaders. Justice Now amplifies student voices by giving them the resources and platform necessary, and serves as an embodiment of the importance of youth voice.