Students across Kentucky have noticed something missing from their classrooms in the past few years. It’s not just textbooks or laptops. It’s not desks or pencils. It’s the people that kids go to school to see, learn from and talk to — teachers. This absence has been nothing short of gaping, leaving classrooms crowded and students on their own.

Districts have struggled to adjust to this disparity. In a 2023 Kentucky Office of Education Accountability survey, 22% of Kentucky principals reported having to increase class sizes, 16% had to eliminate a class and 9% had to combine programs. Students are receiving less individual attention and are left to struggle without the additional aid a teacher provides.

Meanwhile, teacher pay rates fall far behind national averages. Educators across Kentucky are facing a difficult decision: continue teaching, despite the struggles that come along with it, or leave.

Right now, the second choice seems to be growing in popularity. At the beginning of the 2023-24 school year, the Kentucky Department of Education reported 1,702 vacant educator positions throughout the state. One out of eight of those vacancies were never filled.

A severe lack of substitute teachers exacerbates this issue. Almost two-thirds of Kentucky superintendents reported that substitute hiring was a “crisis area” in 2023. The following year, the Kentucky legislature passed a bill allowing substitute teachers to teach with as little as a high school diploma or equivalent certification.

Adding to the struggles are recent actions from state and federal lawmakers, which targeted public school funding and student freedoms. Following his election in 2024, President Donald Trump slashed the workforce of the Department of Education (DOE), and on March 20, signed an executive order to permanently eliminate it. This move could devastate tens of millions of students, including those who receive Title I benefits, attend a special education program or rely on federal student loans.

“It’s really hard to predict exactly how everything is going to play out,” Paul Kepler, an Exceptional Child Education (ECE) resource teacher at Hawthorne Elementary School, said. “It does make me a little nervous not knowing for certain what the future is going to be when it comes to special education funding.”

In 2024, the DOE administered $15 billion in grant money to programs supporting children with special needs under the Individuals with Disabilities Act. Congress enacted this law to ensure that “children with disabilities have the opportunity to receive a free appropriate public education.” Trump has stated that funding for special needs programs will instead be managed by the Department of Health and Human Services, an agency headed by Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Trump also issued executive orders in which he condemned initiatives that promote diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and “gender ideology extremism.” These orders have been met with pushback from teachers nationwide.

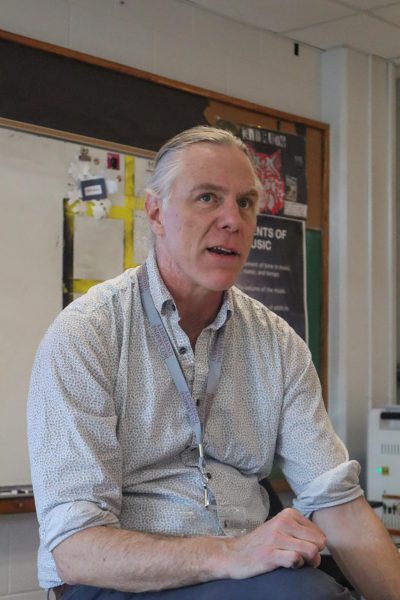

“The argument that your politics is going to sway the student, I don’t think that’s true,” Andrew Kincade, a French and humanities teacher at Waggener High School, said. “Be yourself. Be who you are. And if this is an important thing to you, you don’t necessarily have to teach it as part of the class, but you can discuss.”

On a state level, both sides of the aisle proposed several new laws related to education policy and funding during Kentucky’s 2025 legislative session. These included bills targeting religious freedom, gender expression and DEI initiatives, as well as some that would distribute more money to teacher salaries and free school meals.

Adding pressure to this back and forth is a recently announced lawsuit led by members of the Kentucky Student Voice Team against the state of Kentucky, the Kentucky Board of Education and other government officials. It aims to hold the defendants accountable for not meeting their self-defined criteria for a “quality” education, as set forth by the 1989 Rose v. Council for Better Education decision.

In this political moment, schools, students and teachers are in a central position. Checking social media or turning on the news without seeing another headline about an education-based controversy may feel impossible. It can become difficult to remember that the people working and learning in these systems aren’t just names or stories; they’re an essential part of society.

“Education isn’t necessarily about preparing kids for a job,” Kincade said. “You’re preparing them to be a citizen. You’re preparing them to be a human.”

“It Takes Up Your Whole Life”

The last time Vanessa Hutchison walked out the doors of duPont Manual High School was on March 29, 2024. After a 16-year-career in teaching, she decided to leave the profession to take a website design job at Humana.

“When you’re a teacher, it takes up your whole life,” Hutchison said. “Even when I wasn’t there at school, and sometimes we were there at school pretty late, I was at home on nights and weekends planning lessons.”

It was only Hutchison’s second year at Manual when she left. She spent the majority of her career at Central High School, and Western High School previously. Although she enjoyed the job, she eventually became overwhelmed by the workload, especially after switching to Manual.

“The amount of work students were able to do in the given time was double what it had been for students I previously taught,” Hutchison said.

Even with an extended planning period, she still experienced difficulties.

“That’s 90 minutes a day to plan for five other hours of teaching. And not just plan, but also do all the grading,” Hutchison said. “There’s no way that anyone can get it done in that amount of time.”

Hutchison’s outlook on the future of teaching is bittersweet. She’s not hopeless — she’s passionate about how school districts can be improved, namely by switching to a four-day school week, shortening the payment period for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program and enforcing stricter gun regulations. However, she remains deeply concerned about consistent shortcomings.

“I think that the whole system is breaking,” Hutchison said. “When things break and they’re just irretrievably broken, the only good thing about that is that we get the chance to rebuild them.”

Hutchison isn’t the only teacher frustrated with time, pay, safety and school policies. According to a 2024 Pew Research survey, 77% of public school teachers say their job is frequently stressful and 84% say there’s not enough time during their regular work hours to complete required tasks. Although these struggles vary by district and school type, they are especially pronounced among schools whose students are mainly of low socioeconomic status.

Typh Hainer-Merwarth, an educator with Louisville Visual Art and Wildflowers Academy, has experienced these issues firsthand. In her 10-year teaching career, she has faced numerous difficulties, spanning across multiple schools and districts. She began in JCPS at Stuart Academy, the lowest-ranking middle school in Kentucky, where she struggled to meet the needs of her students.

“A majority of schools in JCPS don’t have a medical professional on staff in the building, and so that kind of stuff will fall on the teacher,” Hainer-Merwarth said. “They have counselors, but often the counseling staff is severely overworked as well.”

Despite some negative experiences with JCPS, Hainer-Merwarth is quick to point out the district’s standout qualities. Among these are its relatively high basic pay and benefits, as well as an exceptionally strong teacher’s union, the Jefferson County Teachers Association.

“It really takes care of and supports the teachers, which is really, really important because teaching is a really hard job,” Hainer-Merwarth said.

Former teacher Kyle Ross also has a multifaceted view of JCPS. He taught English at Pleasure Ridge Park High School (PRP) for nine years and led the school’s theater program, newspaper and swim team. After Ross’ wife’s job took his family to another state for a year, he had to decide whether or not to take his teaching position back on their return. He cites cultural battles within education as the deciding factor of his resignation.

“The book that I taught every year was ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ and it went from being the number one book written in the English language for the United States to being banned,” Ross said.

He was also frustrated by upper-level JCPS administrators, who he said often made decisions about individual schools without consulting any teachers or other employees. Near the end of his teaching career, the district implented a new theater magnet program at PRP, which he felt wouldn’t necessarily be beneficial for the school’s community.

“The principal asked me and the other theater director to go to a meeting with the superintendent so that we could get some of the information,” Ross said. “When we tried to talk to the current superintendent, he literally told us that it was not our job to be there, and that he would talk to the principal at the time, and that would be it.”

One thing Hutchison, Hainer-Merwarth and Ross all have in common is a continued love for public education, despite their troubled histories with it.

“At my core, I still describe myself as a teacher,” Hutchison said. “The overwhelming majority of teachers that are in the classroom right now are busting their butts to do what’s best for kids.”

“There’s Not Much Else Holding Them There”

As more students find themselves without quality teachers, their perceptions have shifted: annoyance and resentment have been replaced by gratitude as more young people realize the burden placed on teachers across the country. No one understands this feeling more intimately than the students who not only see their teachers in class, but in their homes as well.

Abby Ladwig, 17, a junior at Owensboro High School, said her mom has been a teacher for “as long as she can remember.”

Sarah Ladwig currently teaches Kindergarten at Newton Parish Elementary, but was previously employed at Seven Hills Preschool and Hager Preschool. Both schools are supported by Head Start, a federally funded program providing learning and development services for children of low socioeconomic status.

Though the program has served millions since its establishment decades ago, the Trump administration recently announced that its funding may be permanently eliminated under new budget plans. Ladwig left the program several years ago, during a period of other, less extreme budget cuts.

Even as a Kindergarten teacher, Abby Ladwig says her mom still spends countless hours outside of class planning and preparing her curriculum.

“Students themselves get worked up when they have to study more than three hours a night. But have you seen what teachers do?” Ladwig said. “You’d think a teacher would go home and do whatever for their family, but when I’m doing my homework, she’s doing hers.”

From her perspective, most people don’t understand the emotional turmoil that teachers face every day. When speaking to friends about school, she finds herself becoming frustrated with how quickly they jump to conclusions about teachers being lazy or mean.

“They have their own lives,” Ladwig said. “I think right now we don’t see them as humans, the government doesn’t see them as humans, and it’s really affecting us as students.”

Willamina Mook, 14, a freshman at Ballard High School, voices similar thoughts. Her mom used to teach in JCPS at Maupin Elementary School and the J. Graham Brown School, but moved to Francis Parker in Goshen in 2023 for a less stressful schedule. While Mook wants to work with kids and babysits frequently, getting a behind the scenes look at a teacher’s life has turned her away from the career.

“Due to the amount of effort compared to the amount of money that they’re paid, I don’t think it’s something that I would be interested in,” Mook said.

Even students without teacher parents agree with the idea that the career doesn’t look very inviting, especially given popular ideas around pay. Alyssa Faber, 16, a sophomore at duPont Manual High School, says she’s faced pushback from friends and family surrounding her interest in the field.

“They’re like, ‘that would be fun for you, but you would have no money,’” Faber said. “I really want to say making a difference is the priority, it’s the most important thing to me. But because of my family and experiences, just what I’ve seen in life, financial stability — and financial independence, especially — is very important to me.”

This lack of morale among young people surrounding teaching is becoming more evident, with fewer and fewer competing for job positions, even as new openings multiply throughout the state.

In 2023, over two-thirds of Kentucky’s middle and high school principals reported not having enough or an abundance of satisfactory teacher applicants. This number varied by subject, with up to 81.7% and 73.6% of principals reporting no available or satisfactory applicants for physics and chemistry, respectively.

However, passionate teachers are still working tirelessly to provide students with a quality education.

“If they didn’t actually want to teach kids, then they definitely wouldn’t be there,” Mook said. “Especially for public school teachers, there’s not much else holding them there.”

“They’re Not Motivated by the Paycheck”

At Ballard High School, one group of students still looks to teaching as a career to aspire to. Founded in 2017 by Cassidy Cummings, the Teaching, Learning, and Leadership Pathway at the school allows students to take four dual credit courses. Originally just one class on the fundamentals of teaching, the program now offers an array of skill-building lessons.

Many of its students didn’t have a specific passion for teaching when they joined, but eventually found a home within it. Sydnei Rhodes, 17, a senior at Ballard, said she was initially “iffy” about the program.

“When you see how kids act around you, you start to kind of feel bad for teachers in a sense,” Rhodes said. “It kind of gave me a different perspective about teaching.”

Currently, every class in the pathway is taught by Cummings. Several of its students refer to her as a major reason for why they chose to stay in the program, especially due to her unique classroom structure.

“It’s easier to change and modify the work that we do in here,” Marleigh Tripp, 17, a junior, said. “It’s just really nice having a teacher that we can talk with.”

These students aren’t ignorant to the more difficult aspects of teaching — as teens, they’re particularly aware of how teachers are often treated by their peers. Concerns around apathy and behavior are especially worrying for them.

“ It’s not so funny, the things that we used to find funny, knowing what teachers already have to deal with,” Tripp said.

Even as they work toward ultimately pursuing the career, students must simultaneously contend with the growing pressures within it, and aren’t ignorant to doubts from their peers. Abby Faris, 17, a senior, said that the first question her counselor asked her after observing her JCPS Backpack Defense was if she was wary about entering the profession given current controversies around it. As the child of a teacher, Faris has seen both the highs and lows of the job.

“You’re working with a bunch of different kids from a bunch of different backgrounds and all you want to do is help them, ” Faris said. “But you can’t always do that.”

Cummings recognizes that many of her students have a true passion for teaching, and wants to make it clear how rewarding the job can be. However, she doesn’t shy away from the realities of it.

“I try to be really candid with my kids about the rigors and responsibilities and challenges of the job because they need to have a realistic perspective of what they’re in for,” Cummings said. “They’re intrinsically motivated to help others, and they’re not motivated by the paycheck.”

Prior to working at Ballard, Cummings taught as an ECE teacher at Atherton High School and The Academy at Shawnee. Her experience with special education has motivated her to implement it as a core part of Ballard’s teaching pathway, which many similar programs don’t incorporate.

“I think it just makes you a well-rounded teacher,” Cummings said. “And it helps you really understand one of the main purposes of being a teacher in general: meeting individual needs.”

Funding for special education is one of the primary resources at risk under new orders to abolish the DOE. This threat isn’t lost on the teaching pathway’s students, several of whom participate in the Introduction to Special Education course and intend to work with special education students in the future.

“It’s being limited, how much change we’ll be able to make,” Faris said. “But I feel like it also makes what we want to do even more important.”

Concerns around the stability of the career, however, are shared by everyone, even those who don’t partake in that specific class.

“That’s one of the scary parts about it. It’s like, you want to go into this, but are you going to be fully in it forever?” Rhodes said.

“Core Root of Society”

As students, we all know how important educators are — we can all recall those who impacted us, changed our minds or extended a helping hand. Teachers guide us through our toughest challenges and support us in our most dismal moments, however, they receive little beyond gratitude in return.

Our government and society have systematically neglected the public education system for decades, hoping to avoid any consequences. As educators and students have been repeatedly ignored, public education has begun to crumble around us — and the cracks are starting to emerge outside of classroom walls. It’s no longer outdated textbooks or a lack of supplies; it’s a shortage of the most important resource we have.

The numbers are clear. Teachers are leaving, and fast. Students have been left to their own devices as administrators scramble to find replacements, turning the position of an educator into just another slot to be filled.

“She has three classes where she doesn’t even have a teacher,” said Alyssa Pollard, 17, a junior at Ballard, referring to her sister who attends PRP. “It’s up to that sub to scour the internet and find some resources, and she’s ending up doing work that’s not even related to the class she’s in.”

Teachers aren’t just a commodity to be swapped out when needed. They’re essential community members, mentors and even lifelines. But as pay, schedules and new legislation show, they’re not being treated like it. When exhaustion and burnout become too much to manage, districts cut back on expenses by combining classes and switching to alternative teaching methods, cutting off students from the quality education they deserve.

As Abby Ladwig put it, “Education is the core root of society, and if you’re not focusing your time and your effort into education, what are you doing?”