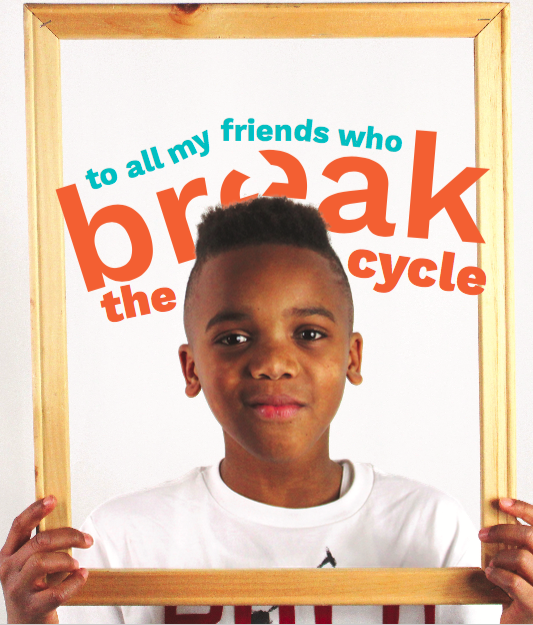

To All My Friends Who Break the Cycle – Y-NOW helps children of prisoners create a future outside of the justice system.

Eleven-year-old Antonio Williamson felt someone place a hand on his shoulder. The blindfold over his eyes blocked him from any sneak peeks, but on March 19, 2017, he didn’t need his sight to sense the anticipation around him.

Antonio turned to find the source of the touch, but the strong hand whisked him back into place. His mentor-to-be then gently patted his arm, a sign of remorse.

“I got a lady!” he exclaimed.

The hand’s owner, Eddie Coy, laughed at this conclusion. Coy then guided Antonio, who followed without hesitation, over to the Country Lake campfire. They were joined by James Hunt, the Y-NOW Director, who explained the seriousness of the ongoing commitment that lay ahead. He directed the mentees to remove their blindfolds, and Antonio was the first to do so. A smile took over his face—a smile that would be engraved in Coy’s memory from that day on.

“I had a feeling that this guy was going to change my life,”

Antonio said.

The Y-NOW Children of Prisoners Program set their course for the next ten months. They would spend time together developing a bond that would have the potential to leave them forever changed. This man could prove to be the role model that Antonio needed to be able to choose the basketball court over a courtroom and sentence structures over a sentencing.

According to Matt Reed, executive director at YMCA Safe Place Services of Louisville, kids like Antonio with imprisoned parents are seven times more likely to become imprisoned themselves. The Y-NOW program strives to break the cycle of incarceration by pairing kids with a mentor who refuses to give up on them. Mentors are required to talk on the phone and meet with the child at least once a week, whether the mentee wants to or not. Even if the mentee slams the door in the mentor’s face, the mentor must keep going to the door every week until the 10-month program ends. It is crucial that mentors put forth the effort to put kids on a positive path.

Prison Policy Initiative, a non-profit organization that exposes the “broader harm of mass criminalization,” reports that 716 people for every 100,000 are incarcerated in the United States, five times higher than most countries around the world. The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics data for 2015 revealed that Kentucky has the 11th highest incarceration rate, sitting at 498 people in prison for every 100,000. These aren’t just statistics; these are people with families, some with young children like Antonio.

Kids ages 11-14 enter the program with a common factor: a parent in jail. As of 2017, 91 percent of Y-NOW alumni have stayed out of the criminal justice system.

“They are driven by goals and dreams and aspirations instead of being caught up in the fact that their mom or dad is in prison,” said Reed. “Everybody in one way or another has said they are going to follow in those footsteps. So, they go from feeling like ‘I’m probably on my way to prison, or being homeless, or worse,’ to ‘I can make something of my life.’”

The mentors come into this program from a wide variety of backgrounds, many of them having full-time jobs and families of their own. They vary in terms of gender, race, socioeconomic status, and origin, and must participate in a full weekend of training in order to learn positive youth development skills and ways of communicating with the middle school-aged group. They are provided resources such as gas cards, but they are limited in the amount they can spend on the kids. It isn’t about having sympathy for the unfavorable situations these kids are dealing with, it’s about building relationships and accomplishing goals.

Sometimes those relationships present challenges. David Brennan has been working as a mentor with the Y-NOW Children of Prisoners Program for four years, but when he was assigned to his mentee, Jordan, it wasn’t exactly smooth sailing. Jordan is a sixth grader who walks with an extra hop in his step and wears his lips pursed in a wide, closed-mouth smirk. He’s quick to interrupt conversation by bellowing “NO” and use profanity in nearly every sentence that he speaks. When he found out Brennan was his mentor, he was overwhelmed with indignation.

Remembering him talk about his love for Chinese food, Brennan told Jordan that he would take him out to eat. As an additional perk, he would allow Jordan to cuss him out. Caught off-guard that he could use profanity without consequences, Jordan let out a faint snicker and agreed to let Brennan take him on the atypical outing. After an hour of conversation, Brennan stopped talking and looked Jordan in the eye.

“So, are you really gonna cuss me out?” Brennan asked.

“No, man, I’m not gonna cuss you out,” Jordan said.

Three weeks later, Brennan and Jordan sat down in a classroom at Safe Place Services for their first group meeting. Brittany Bryant, the Y-NOW case manager, pulled a big white curtain across the room, dividing the mentees and mentors into two groups. On one side of the curtain, some pairs planned their Christmas party while the other group discussed their first community service project.

The kids’ hands shot up at the mention of community service. The program offered them the options of volunteering at the Kentucky Humane Society, a nursing home, or a homeless shelter. It was time to vote. One vote for the Humane Society, two for a homeless shelter, and five for a nursing home.

Brooklyn, an 11-year-old mentee, ponytail sprouting from the top of her head and still in her school uniform far past the end of the school day, let out an exasperated sigh. She was one of the two that voted for the homeless shelter and was not happy with the results. After attempting to suppress her frustration, Brooklyn realized she needed to speak up.

“So homeless people don’t deserve to be loved?” she shouted, cocking her head back and forth.

A mentor placed a hand on her shoulder, but Brooklyn kept her eyes fixed on the discussion leader, Brennan, insistent on getting her way. He asked Brooklyn why she was so passionate about helping the homeless. She explained that she wanted to spend time with the homeless because they didn’t have everything that she had. She didn’t stop for a second to think about the fact that she didn’t have something that many kids her age depend on: access to both of her parents.

“Do you have any friends or family that are homeless?” David asked her.

“Yup,” she replied without

hesitation.

David realized a compromise with Brooklyn was out of reach, so they transitioned into the last activity of the night: “All My Friends.”

In this game, one person stands in the middle of the circle and says, “To all my friends…” followed by a characteristic that isn’t physical or obvious. If it applies to a person, they have to get up and move to a new chair.

One of the mentors started in the middle of the circle.

“To all my friends who have gotten in trouble at school,” he said.

All 15 kids got up and moved.

“Every day,” Jordan mumbled with a sigh.

The mentors moved rather slowly, letting their mentees beat them to chairs and dramatically hanging their heads when they were left standing in the center without a seat. The next mentor began to speak.

“To all my friends who have a family member they don’t speak to,” she said.

Only two kids remained seated.

Games like these are examples of the many opportunities that the kids in the Y-NOW program have to open up about their past or the things going on at home. Although every kid’s situation is very different, they have all been stripped of a parent they can regularly access. These aren’t conversations that kids are sharing at the lunch table. Many feel ashamed or even guilty, as if in some way it’s their fault. Y-NOW gives them a safe place to talk or to listen with others without the fear of being judged or reprimanded, because similar thoughts are cascading through the minds of every kid.

A safe place to talk is only one of the offerings of the Y-NOW program — another is goal-setting. At their first meeting, the mentor and mentee are both required to set two challenging goals for themselves. Throughout the 10 months, the pair encourages each other to accomplish those goals.

Cam’Ron Ayer was a kid that Reed said was “particularly special.” Ayer came to the program because his grandmother used to run the kitchen at Safe Place Services, and he was in dire need of some attention. His father is still serving time in prison for shooting at a police officer. When the 10-month program began, Ayer was angry. He got in constant fights at school and often faced suspension for skipping class entirely. Before his father went to prison, Ayer had a good relationship with his dad. They did everything together.

“So, we’re talking about a kid who could either be dead, homeless, or incarcerated by now or certainly on his way to that. It’s giving me chills to talk about it,” Reed said, with a quiver in his voice.

Ayer’s goal was to become an artist. As a freshman in high school, he was given a section in a senior art show. Not only was his artwork featured, but he won best portfolio and best overall piece in the entire show, beating out four talented senior artists and eight others. This was the same kid who rarely showed up to school just three years prior.

In a Facebook post announcing his achievements, Ayer said, “I believe in my gift and plan on continuing my work for the rest of my life. Today, I truly understand what happiness feels like.”

Ayer is currently attending Western Kentucky University on a full art scholarship. The Y-NOW program provided Ayer with the tools and confidence to achieve his goals and make something of his life, but the choice to be successful was one that he had to make on his own.

Many of the mentors struggle with watching their mentees endure such difficult situations. The mentors are not allowed to tell the kids where they live or take them home. They act as mother and father figures, but these mentors cannot be the child’s mother or father, as much as they may be tempted to step into that role.

“When you hear about all the things that they’ve gone through, you just want to wrap your arms around them, take them home, and raise them and make everything go away,” Reed said. “But it’s not about rescuing them, it’s about helping them save themselves.”

It may be the girl who rarely speaks at the lunch table or the boy who sits across the room in algebra class, or maybe it’s his best friend, but kids are dealing with the effects of incarceration everywhere. While the program has doubled in size over the last 18 months and given many children a sense of belonging, Reed is always looking to improve. Finding kids to join the Y-NOW program is not the issue. The problem lies in recruiting mentors who are willing to put in hours of their time and make promises that they’ll keep. And even then, Reed can’t help but ask himself, “Are we doing enough?”

Y-NOW has made major strides in decreasing the likelihood that kids with incarcerated parents will go to prison, but it is not stopping here. Reed says, as challenging as it may sound, his goal is to break the cycle of incarceration in Louisville.

The time had come for the end of the program, and Coy and Antonio were pondering what their future together would look like. For some mentees, the mentor would be a facilitator for positive change, but they may lose touch over the years. But Coy and Antonio are different. Their trust from the start made it clear that they were meant to be in each other’s life for longer than the program required. Coy was passionate about stopping the cycle of incarceration in Louisville and felt compelled to maintain his exclusive mentorship with his mentee.

Tonda Jackson, Antonio’s grandmother, questioned Coy about his plans following the program graduation. She was concerned that the first piece of stability Antonio had had in a long time would be ripped right from him.

The subject of their conversation was eavesdropping around the corner, equally anxious about what was to come. Coy turned his head to see him listening in, and their eyes locked. Antonio shook his head in disapproval, and Coy made his decision.

“I love him,” Coy said. “That’s kind of the bottom line.”

The future of Coy’s and Antonio’s relationship is out of view. They don’t know what’s next, just that there’s a future that they want to spend together.

Although Coy can’t erase Antonio’s past, he can give him what he needs to reach a brighter future than that of his parents — brighter than statistics would have others believe. The Y-NOW program addresses the reality of these situations; it aims to lead kids, like Antonio, away from that cycle.

After the program ends and they call the last name at graduation, some mentors may move on to help other kids through the program, but Coy says he knows where he belongs — and it’s right next to Antonio. «

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.