Split City

The Root of the Problem

I went to Meyzeek Middle School, a school that, by numbers alone, is one of the most diverse schools in Kentucky. But despite that fact, my seventh grade language arts class had only one Black student. It wasn’t until a year later that I realized just how strange that was, especially since the rest of Meyzeek is so diverse. That’s when I started to think about the demographics of my middle school, and it struck me just how separate I was from most of the Black students.

In Meyzeek, I was part of the Advance Program classes. The Advance Program, part of Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS), is different from Advanced Placement (AP), a program run by the College Board. However, both are known for their notorious lack of Black students. As a middle school student, not only were there few Black students in my classes, I was put into ‘traveling groups’ that kept me from meeting any others outside of my classes. Therefore, the only faces I saw all day were my classmates. I often found myself wondering how a school that boasts its diversity could have such separation. Even as I went into high school, I realized that the Advanced Placement classes barely improved in diversity.

When I learned about housing segregation, it became clear to me: the divides in housing led to the divides in schools, and the students in Jefferson County are suffering as a result.

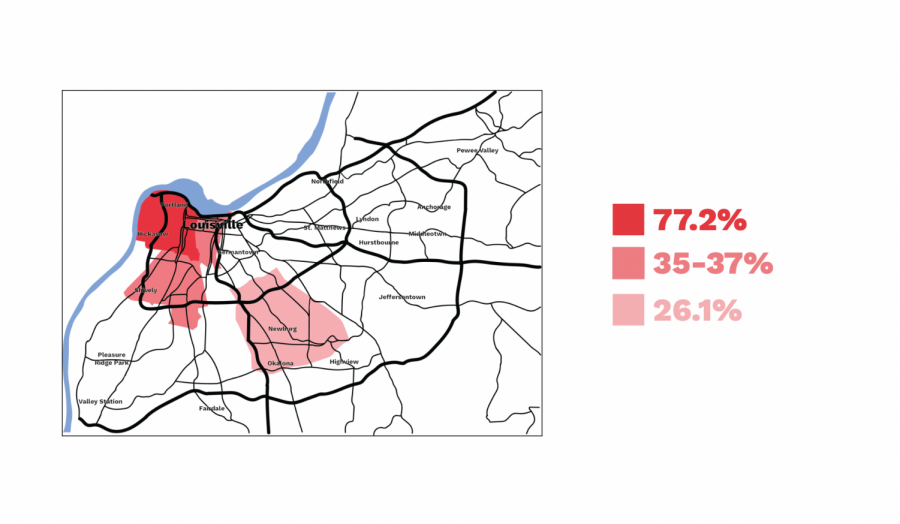

Racism in Louisville has affected all aspects of life for African-American citizens, down to where they live. While the racial split in neighborhoods was much more drastic in the past, even today you can see disparities. The West End is majority Black, while the East End and other areas of Louisville are mostly white. On your own street, you may have neighbors of a different race, but more often than not, neighborhoods are concentrated into groups of each race. These are the lingering effects of housing segregation.

The current student assignment plan — the process of sorting and transporting students into different schools — was originally created to counteract the housing segregation that is present in our city. The JCPS Board of Education, not able to tackle the housing issue on its own, instead transports students across the county to patch the split in our city. However, some say it is only a Band-Aid over a bullet wound.

History

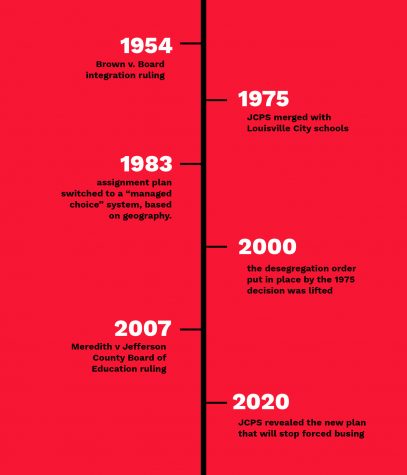

In 1954, in the landmark court case Brown v. The Board of Education, the Supreme Court decided that separation in schools was unconstitutional and ordered the beginning of immediate desegregation of schools. Despite this, it took over 20 years for all of the Louisville area public schools to be integrated.

Ever since the first student assignment plan in 1975, JCPS has constantly tweaked and revised the plans. Before then, there were two different school districts: JCPS and Louisville City Schools. When the Brown v. Board decision was made, Louisville City Schools integrated immediately after, while the county schools did not.

While the local city system had a large percentage of Black students, the county system was mostly white.

In 1970, this divide was caused by years of white flight (white people leaving urban areas in favor of all-white suburban neighborhoods to avoid desegregated schools). Because of this racial difference between the city and county area, it was still difficult for Louisville schools to be truly diverse. As a result, advocates of desegregation argued for merging the two systems.

Unfortunately, many white families, especially parents, did not agree with this decision. They incited violence and riots all over Louisville, sometimes going as far as “throwing rocks at buses of Black children going to schools,” Dr. Wynkoop, former Special Advisor to the Superintendent during the desegregation, recalled. “It must have been horrific for kids going to some of the schools.” Tasked with the problem of uniting the split city, JCPS continued to work on different plans to better carry out integration.

The JCPS Board’s first plan was race-neutral. It attempted to overcome housing segregation throughout the city by sorting students into different schools using the first letter of their last name, regardless of race. While it was successful in making schools more diverse, neighbors could end up going to different schools across the city.

In 1984, the assignment plan switched to a ‘managed choice’ system based on geography. It grouped neighborhoods into regions with one school for each area, called a reside school, that students could attend, similar to what we have today. With this change to the plan, whole neighborhoods would be assigned to a specific school instead of singular students.

While this worked better than the earlier last-name based system, it still prevented students from going to high schools closer to their homes, since many West End students’ reside schools were placed across the city to combat segregation.

Eventually, in the late 1990s, attorney Teddy Gordon sued JCPS on behalf of a group of families who wanted their children to have the opportunity to go to Central High School, a magnet school. Before segregation, it was the only public high school that Black kids could attend, and it remained historically significant until present day. JCPS segregation policies limited the amount of Black students in any school to 50% of the population, and because Central drew few white students, fewer Black students could attend as a result. That legal case led to the debate over the efficacy of the JCPS desegregation process: the city needed to strike a delicate balance, working against segregation without forcing excessive busing on West End students.

Then, in 2000, the desegregation order put in place by the 1975 decision was lifted. JCPS had the option to switch to a neighborhood school system, but continued to use a race-based plan. This plan, despite having good intentions, maintained the unfair burden for West End students who had to be bused far away from their neighborhoods and mixed into majority white schools. In that way, the race-based plan maintained diversity, but with a cost to the students it ought to benefit.

“Not only were we forcing students from one portion of the county to travel, while we don’t require students from the East or the South end of the county to travel, we’re also breaking up neighborhoods, relationships, et cetera, in the West End of Louisville based on almost nothing at all,” said James Craig, a current member of the JCPS Board of Education.

In 2007, another legal case was filed on the behalf of Crystal D. Meredith and her child, Joshua Ryan McDonald, who was white and not assigned to his first choice school, Bloom Elementary, due to the race ratio guidelines. This case went all the way to the Supreme Court, and became known as the Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education case. Its ruling? Schools could no longer sort students by race alone.

In response, the JCPS Board of Education amended the student assignment plan to take into consideration family income and educational level and not just race. This system guided assignment for the next twelve years, though it continued to send more Black students from the West End to far away reside schools.

The New Plan

After years of disproportionate busing, a new student assignment plan was born. On June 10 of last year, Dr. Marty Pollio, the current JCPS Superintendent, and the JCPS Board of Education proposed yet another change to the plan, calling it the ‘dual reside plan,’ in which West End students will have more of a choice in their school. If passed, it would go into effect the 2021-22 school year for incoming sixth and ninth graders all over Jefferson County.

Instead of requiring West End students to be bused far away from their neighborhood, this new proposal aims “to also provide them with an option that’s closer to their home,” Craig explained. To make this possible, the Board has been funding renovations for existing schools and construction of new schools in the West End to improve the options for students wanting to stay near home. Saying the changes are “trying to fix, essentially, the sins of our fathers,” Craig hopes the plan will lessen the burden upon West End students’ shoulders . The major setback that prevented JCPS from providing West End students with the choice to stay near their homes was the lack of funding and the pushback from area residents when faced with higher taxes.

Nevertheless, they have recently begun two new projects that, when completed, could mean better opportunities for West End students wanting to remain in their neighborhood. The Academy at Shawnee, a Louisville middle and high school in the West End, previously had a capacity of 600 students. For the past 40 years, the third floor has been vacant due to it being declared structurally unstable. Recently, it has undergone a $40 million renovation that will be safer and hopefully hold many more students — possibly 1,500 by the time it’s done. The other recent project is a new elementary school in the Broadway corridor of the West End, which will combine students from Phyllis Wheatley Elementary and Roosevelt-Perry Elementary. Both school buildings were only at about 50% capacity, and were in bad condition, having deteriorated over the years. By merging them, the Board hopes to give the kids in that neighborhood a better and safer elementary school.

What’s Next?

Now, what does this mean for the future of schools? What the JCPS Board of Education is hoping for is better educational opportunities for students, both now and in the future, while still providing students with the ability to choose what they want for their schooling. Throughout history, the West End community has been overburdened, and the JCPS Board members want the new dual reside plan to give the students there better future prospects while allowing them to stay connected with their community.

For example, extracurriculars are popular among students of all ages and backgrounds, giving opportunities to learn and do new things that you don’t get in school. And not only are extracurriculars enjoyable pastimes, they also contribute to a sense of community within a school. However, since many parents are working around the time schools release, kids bused an hour or more away from their neighborhood might have to take the bus and miss out on extracurriculars. This is the case for some students from the West End, who have limited transportation. With the addition of students’ choice, Craig hopes that “there will be an increased sense of belonging for those students who choose to attend a school that’s closer to them.”

Along with more extracurricular opportunities, the school buildings themselves will be more suitable and safe for the students and staff within, like the Academy at Shawnee and its third floor renovations. Furthermore, the Board plans to add more staff members (administrators, counselors, and teachers) to each school building to increase the number of positive interactions between students and adults, and therefore further increasing the sense of belonging and the likelihood of success for those students.

Unfortunately, there are downsides to this plan. Some Louisvillians are concerned that if too many Black students remain in their own neighborhood, the persistent housing segregation in our city will cause all schools to become more homogenous. When students learn in diverse environments, they are less likely to be biased against other races and ethnicities. Not only do students become more open-minded in integrated schools, but they often perform better academically, too. The debate is not just about maintaining racial balance, but trying to figure out the best possible environment for all students.

The need for West End students to have more choice in their education is the main reason behind the dual reside assignment plan that has been in the works recently, but whether or not the plan’s pros outweigh the cons is widely debated.

Trying to maintain racial diversity is a righteous goal, and while JCPS has good intentions, the plans so far have all forced West End students to take the brunt of busing. With this new plan, West End students are free to choose if they want to be bused to schools outside of their communities or stay near their homes. Denying West End students that choice has been a constant in previous student assignment plans.

However, if more West End students choose to stay in their neighborhoods than choose to be bused, then the changes might unintentionally make schools all over Louisville become more segregated. For lack of a better phrase: schools outside of the West End risk getting whiter.

“We’re gonna have to monitor that very closely,” Craig warned, looking to the future. This potential loss of diversity is because of one simple fact: housing segregation remains.

“It’s just as important for kids not living in poverty, perhaps kids living in affluent neighborhoods, to see students of color as their peers, and to develop relationships,” Craig added.

Although the fear of resegregating is a valid one, as Catherine Fosl, Director of the Anne Braden Institute at the University of Louisville, puts it, “I think it’s easy enough for white people to express that fear, without having to live its consequences as brutally as a lot of Black families have.”

And therein lies the crux of the debate.

Housing segregation is truly the root of the problem. If Louisville does not take initiatives to fix the split in our city, diversity will never truly be achieved.

“Really trying to overcome that, and getting everybody on board with the collective good, has to happen, or we’re never gonna fix or overcome the challenges of public education,” Craig said.

If Louisville does not take initiatives to fix the split in our city, educational diversity will never truly be achieved.

Because housing segregation still splits our city and concentrates Black students in the West End, school desegregation has always depended on sending them away from their homes. What makes it so hard to fully support the new plan is because it sets up a debate between fairness and integration. Ever since the first plan, this problem was guaranteed to arise, and now JCPS and Louisville are being forced to deal with it. Now JCPS must choose: diversity or choice?

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.