Bridging the Gap

The disparity in Louisville’s public education system is apparent; one organization aims to change that.

Photos by Mia Leon

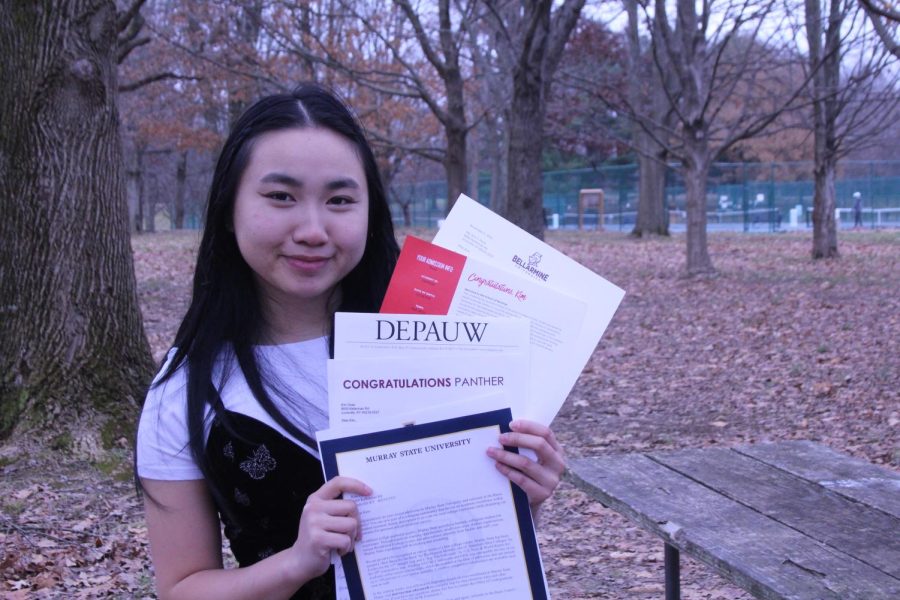

Fern Creek High School senior, Kim Doan, 17, has been a part of Ivy Plus Academy, a program that provides mentoring and resources to minority students like Doan, since her freshman year. Doan has received several early acceptance letters to her dream colleges as a result of the preparation and guidance offered by the Ivy plus program. She stands in Tom Sawyer Park on Dec. 19 proudly displaying her acceptance letters. Photo by Mia Leon.

Sunlight filtered through the trees as Kim Doan stopped with her fellow classmates, surrounded by the sound of swaying leaves. Looking up, Doan could see peeks of blue sky through the gaps between tree branches. Their hike at Cedar Ridge Camp had culminated in this stop.

Arriving at the camp with Doan were other Fern Creek High School freshmen. They were all new members of Ivy Plus Academy, a program that provides mentoring and resources to low-income, first-generation, and/or minority students throughout and beyond highschool based within Fern Creek. They all knew few people and had brewing doubts about the academy’s expectations. Doan had hoped to be accepted to another high school but was denied. Her last-minute entry into Fern Creek felt like a last resort.

During the retreat though, surrounded by nature and welcoming advisors, she relaxed, laughed with new friends, and even started to feel excited for the new year.

The students were split into groups of five and presented with a large wooden plank. They were told each member of the group had to fit their feet on the board. Any technique could be used to fit their team members. Anyone who fell off the board lost.

Each round, the teams were presented with a smaller board. As laughter and shouts rang in the air, students locking hands and shooting out arms across gaps of space to steady a teetering teammate, a seed was being planted in Kim and her peers’ minds: supporting each other creates a community where everyone is stronger.

Ivy Plus:

Ivy Plus Academy’s focus and mission is to create an equitable community that meets underrepresented student needs and opens up opportunities to gain acceptance to elite colleges all over the United States.

The freshman leadership retreat is one of many annual bonding kick-offs for each new cohort. The retreat starts to build a community of support between students, one they will need through the rigorous curriculum and extracurricular activities of the next four years.

A nearly full wall of college pennants greeted us when stepping into Beau Baker’s classroom for the first time on Nov. 18. Flashes of blue, red, and purple were plastered all around. Baker is the founder and dean of Ivy Plus Academy. He told us the placement of the pennants was intentional. Whenever students’ eyes stray from the projector screen or a lecturing teacher at the front of the room, their daydreams will include these colleges. Every single pennant was placed and signed by a previous student of the academy who got into the college displayed.

Now a current senior, Doan is looking to add her name to the list of Ivy Plus alumni and their wall of pennants. Her time at Ivy Plus made her realize her doubts about Fern Creek were unfounded.

“Fern Creek is the type of school most students are usually ashamed to be in because of the past,” Doan said. “However, I love it here and I am proud.”

Baker shares this pride. After he left the Navy in 2004 as a Surface Warfare Officer, Baker had no clue what he’d do next, and although he received a Masters degree in English, teaching was the last thing on his radar. Many who leave the Naval Academy so soon in their career usually end up working for defense contractors.

“I had some interviews and job offers and I was just like, I would really hate doing any of this by being a part of that nonsense. And so I kind of just fell into this job,” he continued.

Baker was enrolled as a teacher at Fern Creek High School knowing nothing about how to connect with students. He explained to us that it was difficult navigating the ways of a teenager’s world despite once being one. Not long into his career, he began to notice a trend within his senior classes. Every January he would ask them the same question:

“Hey guys, where are we? Have any of you applied anywhere yet?” and he always received the same answers,

“No, don’t the colleges come here?”

This sparked a revelation in Baker’s mind. He realized the knowledge provided to students about their futures was very limited, leaving them with only assumptions to guide themselves through the college process. From this point on, Baker started working one-on-one with students and their families to educate them about the college process.

“I just started working with my juniors in class and their families and said, ‘Guys, let’s talk about this on the front end. How can this work?’” Baker said, concerned.

This continued for about ten years, until the former principal of Fern Creek, Dr. Nathan Meyer, offered as much help as possible to kickstart the Ivy Plus Academy. With no financial support from JCPS, Ivy Plus Academy relies on money for resources through private donations and student fundraising.

The academy is centered around classes that will prepare students for their upcoming years in college. Students apply freshman year and, if accepted, begin taking higher-level courses to build a resume that is appealing to colleges all over the U.S. Along with this, Baker dedicates his time to developing an understanding of the struggles of minority and first-gen students in the college process.

Although the college process typically begins senior year, Baker preps his junior cohort students during after school meetings throughout the year. During his December meeting, Baker handed out a timeline mapping what the rest of each student’s junior year should look like.

Along with the timeline, he included a paper that displayed a long list of distinguished colleges.

As the students looked down the list, their faces filled with worry. Their fingers skimmed the pages faster than they could process the words. The brief moment of silence came to an end when a student from the back row raised his hand.

“What does this mean?” he said.

Baker explained that these colleges were options. This list was only to provide insight into the realism of each student’s choice. He wanted his students to look at this list and think about what they want, nothing else, so their family and Ivy Plus can figure out the rest.

The academy strives to prioritize the student’s aspirations while taking into account their family’s limitations. To do this, Baker hosts an annual one-on-one meeting similar to the ones he did before Ivy Plus was created. During the meeting, Baker guides each family through a conversation about yearly income, the FAFSA, and other considerations that could affect the student’s decision and acceptance. They work together to pick apart these factors and find ways to overcome them, making the possibility of college tangible.

A Historical Standpoint:

In addition to helping seniors get into college, Ivy Plus Academy is fighting a bigger issue in the U.S.: academic inequality.

The concept of academic equality was introduced in 1966, when the Equality of Educational Opportunity, also known as the Coleman Report, was released. The U.S. government commissioned sociologist Dr. Coleman to determine the impartiality of public schools across the nation. Contrary to previous models, Coleman surveyed the equality of outcome rather than the equality of input.

In other words, just giving schools identical, new textbooks does not mean a district is equitable. For instance, one of those schools may have a large population of students who are behind their grade level in reading. This school would require more resources, such as more experienced teachers, to get their students to an equal playing field. Ideally, all students would have the same opportunities in school regardless of income, race, or gender. But in the U.S., academic achievement is heavily correlated with household income.

A classic example is the relationship between SAT scores and income. As median family income increases, so do individual subject tests and overall SAT scores. The trend is seen in the ACT as well. Students who come from a family of high income can often afford tutoring or test preparation books. Time is also a valuable privilege. Working a part-time job or watching a sibling while a parent is at work cuts into study time.

The effects of this correlation hurts students in the application process. Universities have tried to combat it by using a holistic admissions process, reviewing course rigor, GPA, extracurriculars, honors, essays, and test scores equally. But these standardized tests still hold weight with prestigious universities and scholarship consideration. So although test scores do not immediately get you in, they get your foot in the door.

A basic understanding of the college process is critical as well. Iosef Casas Gutierrez, a 22-year-old Ivy Plus Academy alum, felt the impact of this when he emigrated from Peru with his family. Both his parents received post-secondary education in Peru, but in the U.S. their degrees were not recognized. As the oldest of his extended family, Casas was the first to enter the college process in a new country. Like Doan, Casas also did not know much about Ivy Plus.

“My first impression was simply that Ivy Plus would help me get into a good college,” Casas said. “Whatever that meant.”

Ivy Plus introduced and guided Casas through this extensive process. The academy assisted him in finding extracurricular opportunities, studying for the ACT, and writing applications. Most of all, Casas was given a chance to believe in the abilities he had all along.

“Ivy Plus pushed me to take a risk to apply to schools that by scores alone, I fell below average,” Casas said.

In order to understand how academic inequality starts, we spoke to Dr. William Bunton and Dr. Stephanie White from JCPS’s Diversity, Equity, and Poverty Division.

White, the diversity hiring specialist for JCPS, explained the gap of academic achievement can start before a child is born.

“I would take it all the way back to birth, because when we talk about children, and childhood development, and language acquisition, it goes really back to prenatal care,” White said.

The conditions a mother is in, such as her access to preventative care and healthy foods, affects the cognition of her child. Furthermore, the household environment a child grows up in will affect their preparation for school. For instance, having a parent around to read and talk makes a difference in a child’s vocabulary. If the student has an unstable homelife, their ability to come to school and learn is often hindered.

“You have some kids that start off with everything they ideally would need, ready to roll, and some kids that have minimal things that they need. So, of course, those who have less, tend to not be as prepared to start school,” White said.

Although seniors in the college process may be fighting years of developing inequity, supporting students with necessary resources can bridge this gap.

Bunton, the executive administrator for the division, recommends avoiding a deficit mindset, which focuses on problems over potential.

“A lot of times that’s what people come with: ‘You don’t have the ability to’ and ‘You can’t.’ Some of our teachers unfortunately have that mindset as well,” Bunton said.

White also spoke on the benefits of students being exposed to a constant college culture. This culture can include parents taking their children to college events such as football games or encouraging students to think ahead to their future goals.

The pennant wall is one way Ivy Plus promotes this culture at Fern Creek. Students are able to envision themselves achieving this goal, even if they are in the minority, the first in their family, or previously thought they could not achieve it.

“If you set the bar and your scaffold, and you help kids, they will reach the bar.” Bunton added.

A School’s Responsibility:

As student journalists, we had to ask ourselves: why are these programs needed in the first place?

But there was an even more challenging question at the foundation of it all: how much responsibility do public schools hold in ensuring student success in all areas of their life?

Historically, schools only provided a place for education. Starting in the 1960s, schools started implementing social programs to combat poverty. In an interview with On the Record, Marty Polio, JCPS superintendent, discussed the tug of war for schools. Between nurturing students and being responsible for larger societal issues like food insecurity, homelessness, and mental health needs, the district is torn.

“I am a firm believer that these are societal issues that the entire community should be wrestling with,” Pollio said.

This is where the real question of responsibility comes in. The administration is working to provide support to their students while abiding by the funding limitations set by the state government.

“The Kentucky Constitution and the statutes that guide our finances are extremely strict. Probably more strict than almost any other entity, and you can only use funds that directly impact students that are enrolled in JCPS at that time that affect the learning,” Pollio said.

He explained using a small example.

When driving past JCPS schools in the morning or evening, crossing guards can be seen directing traffic for student safety. In 2019, Metro Council ceased funding for guards due to budget cuts, putting the responsibility on JCPS.

“The attorney general has ruled several times that JCPS is not allowed to pay for crossing guards, because it doesn’t impact immediately what goes on inside of a school,” Pollio said.

In a large school district like JCPS, public schools often have to prioritize some issues over others. This means the immediate needs of kids in school come before post-graduate plans.

From a student’s perspective, although we know college isn’t a determining factor in success, we were conditioned to believe otherwise.

Ivy Plus Academy empowers students with a choice, one they might not have been afforded before. Students choose to apply to the program, which colleges to apply to, and which path they would like to take. They are supported to open up new doors of opportunity.

“Why am I going to limit my kid’s threshold for a future?” Baker said with a stern voice and sharp eyes. “These kids don’t owe us a damn thing. We owe them the ability to maximize their potential and future.”

Before they enter that future though, Ivy Plus seniors experience the culminating moment of their four years of hard work. The start of college acceptance announcements, a time seniors both dread and anticipate, had Iosef Casas more anxious than his classmates. While most of his peers had been able to celebrate their acceptances, Casas was still awaiting the release of the Ivies’ first-year decision admissions.

He started with Yale’s email.

Denied.

Casas moved on to Cornell.

Denied.

Next up was UPenn.

Denied.

Disappointment starting to sink in, Casas remembered the last unread email: Dartmouth. Taking a breath, he loaded the application portal.

Accepted.

Sitting, shocked and elated, Casas did not celebrate alone long. The weight of his accomplishment fully sank in when he showed Baker, seconds before being pulled in for a hug.

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.