Bleeding Pink

The pink tax can make women’s lives harder, but addressing its injustices head-on has the potential to lessen the issue. Writing by Kendall Geller & Michelle Parada | Design by Noa Yussman | Illustration by Stella Ford

Photos by Anna

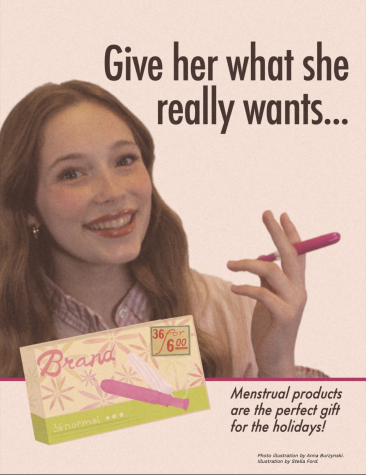

Photo Illustration by Anna Burzynski.

I walked through the sliding glass doors with a five dollar bill wadded up in my hand and six minutes to spare.

I marched toward the women’s health aisle, and all I saw was pink. Fuchsia and rose-colored boxes of menstruation products lined the shelves, a stark contrast to the surrounding aisles of randomly-colored items. I grabbed the smallest box of light tampons that I could see, snatching them off of the shelf and making the trek back toward the checkout aisle. There was only one open self-checkout station, which I practically sprinted toward in my rush to leave the store. I shoved the five dollar bill into the machine, and to my surprise, the remaining balance did not fall to $0. I checked the carousel, making sure I had purchased the right thing. A box of generic, Target-brand tampons stared back at me.

Five dollars for 36 tampons wasn’t even enough.

Why wasn’t it enough?

On average, personal care products marketed toward women are almost 13% more expensive than those marketed toward men. This includes things like razors and razor cartridges, lotion, deodorant, and shaving cream. These products are necessary to maintain physical health and well-being. So why is it that it costs more to be a woman?

This cost difference is known as the pink tax. The implications of the pink tax are relevant to all women everywhere, but college students and newly financially-independent people experience the brunt of its negative effects. Many teenagers don’t have to think about the cost of their products, because they aren’t the ones that have to pay for them. However, if this financial safety net is removed, such as in college or further into adulthood, it is possible that they will experience the strain that these basic necessities have on their bank account. Abbey Maxey, a student at the University of Louisville (UofL), said that she has never purchased a women’s razor for this reason.

“It’s just egregiously expensive compared to a men’s razor with the exact same thing,” Maxey said.

Aside from personal care products, women are already heavily encouraged to purchase products that make them more pleasing to societal beauty standards: makeup, hair products, skincare products, and latest fashion pieces that adhere to the latest trends. That is simply not the same for men, who can, for the most part, get by while doing only the bare minimum, their expectations not nearly as high as they are for women.

This constant demand to purchase the newest products isn’t supported by many womens’ financial realities. There is a constant push to make ourselves into “better women.”

“This tax also occurs in a society where women earn, on average, when they work full time year-round, 82% of what men earn,” Dr. Karen Christopher said, a sociology professor at UofL who researches women, gender, and labor.

The lessened income provided by the wage gap leaves women on already-unequal footing in terms of their financial situation, and the pink tax only serves as an added expense. On top of that, the pink tax includes one additional issue that is not applicable to most men: periods.

In Kentucky, menstrual products such as pads and tampons are included in the 6% sales tax that is placed on luxury goods. The labeling of menstrual products as non-essential, or luxury, means that food stamps and other relief programs cannot help pay for them. This inaccessibility is especially relevant for those who are incapable of affording the products necessary to maintain a sanitary lifestyle.

Homeless, or houseless, women are amongst the group of people that often have trouble acquiring menstrual products. This can be attributed to many factors: their costliness, short-supply of period products in shelters, or not having the transportation necessary to visit a store that sells such products.

According to Louisville Metro Council Member, Paula McCraney, the inaccessibility of menstrual products can have negative health impacts, especially for homeless women. Many are forced to leave products such as tampons in for longer than is medically advised, putting them at risk for toxic shock syndrome, which is a condition caused by bacteria inside the body that releases harmful toxins. The American Medical Association states that some women who cannot afford menstrual products attempt to construct makeshift sanitation products, which can be dangerous and have the potential to cause vaginal and urinary tract infections, severe reproductive health conditions, or toxic shock syndrome.

Houseless women are expected to either ration their supplies or put their health at risk for products that are necessary for health and sanitation. This should not be normalized. Denying people these basic necessities not only impacts health, but can be dehumanizing to the people affected.

“People who are houseless should not be put in situations where they are embarrassed or humiliated because they’re on their cycle and may have bled through, for example,” Rep. Attica Scott, said. Scott is a Democrat serving Kentucky’s 41st district and has been incredibly vocal in her fight against the pink tax.

“For those of us who have menstrual cycles, it’s not an option. Right? These products aren’t optional. We have to have them,” Scott said.

Aside from menstrual and hygienic products, the pink tax can also be seen in everyday items like childrens’ toys, stationary supplies, clothing, and more. An article published by Slate incorporated a price-comparison study that included two scooters of the exact same make but in different colors. The red scooter was priced at $24.99, while the pink one, labeled “Pink Girl’s Scooter,” was $49.99. Supposedly, the only difference between these two products, besides their color, is their audience. The gendering of colors is extremely prevalent in marketing, where pink and purple products are marketed toward feminine consumers, and red and blue items are marketed toward masculine consumers.

This gendering of colors originated in marketing in the 1950s, when some advertising companies used pink in campaigns directed toward women, forever branding it as a “girl color.” Before this, it was the opposite. Pink was assigned to boys since it was viewed as the younger brother of the “stronger and more powerful” color, red. Blue was seen as dainty and modest, making it “better-suited” for girls. The modern association of pink with femininity is not only the fault of advertising, but continues to be facilitated by it. The “Pink Girl’s Scooter” is targeted toward a more feminine consumer, and consequently, is more expensive.

The gendering of colors places people and their identities into strict boxes. In reality, colors should remain androgynous and free to be perceived however one chooses. The “pink” tax is only associated with women, which adds to the problematic idea that identity is simply black-and-white, rather than a multifaceted concept that can be interpreted in an endless variety of ways.

It is necessary to address all of the problems and implications of the pink tax. But first, people must know what it is. This presents another issue.

The pink tax isn’t something that often makes headlines, as there are often bigger or more pressing issues that are more obvious to the public. Many don’t even realize the pink tax exists; they are used to buying either only men’s or women’s products, and thus, may not even notice the difference in prices. People in the U.S. rarely think about it long enough to consider the injustice of the phenomenon. It’s just something that happens. Visiting a store and having to pay eight dollars for a pack of 20 tampons is annoying, yes, but it’s not unusual. To put this in perspective, on average, it costs $5.36 to purchase a pack of cigarettes in Kentucky. Something so unhealthy often costs less than something that is necessary for basic health and hygiene.

In Louisville, Scott has spoken out about the pink tax. She proposed Kentucky House Bill 27, which would provide an exemption of the 6% tax on feminine products, erasing the designation of menstrual products as luxury goods. Scott spoke about how this is something that is heavily needed for all women, but especially for women that cannot afford these necessary products. Scott’s original bill would have been implemented on July 1, 2022. However, it has not been passed and nothing has changed.

Still, other states are seeing these changes take place. For instance, the state of Virginia reduced the tax from 7% to 1.5% in 2019, and this year, they decided that the complete removal of the tax will go into effect on January 1, 2023. While this change shows progress, it took four years for the state government to realize the benefits of a complete removal of the tax.

Part of the problem is that politics are largely dominated by men. Women currently make up 27% of the U.S Congress, which shows progress given that this is the highest it has ever been. Regardless, that is still 73% men, who are less likely to vote on or even notice womens’ issues such as the pink tax.

“It’s not on their radar the way it is for us when we experience this once a month. This is part of our life,” Christopher said.

Nevertheless, there are ways to make them realize sooner that such changes need to be made.

We don’t have to sit around and wait for policymakers to decide to pay attention to this issue. Chances are, they won’t.

This is especially true in places like Kentucky where the state legislature generally ignores or strikes down issues of this matter, no matter how hard the push is from within the chambers. For example, House Bill 27 was refused a hearing by all members of House leadership.

“I did my part. I tried. I called, I emailed, I met with legislators. I did everything I could to try to get the bill passed,” Scott said.

All of her attempts to pass the bill were shot down.

That leaves it up to us.

For those above 18, the best thing to do is vote for policymakers that are willing to make these changes. In the 2018 primary election, just 54% of the total eligible voting population cast their votes, and only 24% of eligible voters aged 18-24 participated in the election. Meanwhile, 64% of the 65 and older voting populations showed up at the polls.

This disparity does not live exclusively in the statistics. Their real-world consequences lie in the decisions being made by the people they won’t affect.

However, action is not limited to eligible voters.

“You have the power, you have the ability, you have the right to contact your local and elected officials and tell them, ‘Make this a priority,’” Scott said.

If we want to experience change for ourselves, we need to act. Scott encourages young people to use the resource lying at our fingertips: social media. She wants us to go live and make posts so that people understand that we can actually do something to address, and hopefully solve, this issue.

There are still many steps that we have to take, but we are certainly on the right path. Young people especially are demanding change for themselves and future generations. For instance, Scott got her inspiration for House Bill 27 from a group of UofL students that came to her with an idea to propose the erasure of the pink tax like those that they had seen implemented in other states.

This progress doesn’t change the fact that women have and will continue to struggle because of the pink tax. Discrimination against women is as heavily integrated into this country as democracy. It is bleak and frustrating, and if we continue to sit around and wait, it will not stop being our reality.

“It’s kind of the larger cost of being a woman,” Christopher said.

But it doesn’t have to be.

Donations are collected through The Publishers, duPont Manual High School's booster club for J&C. On The Record relies completely on sponsorships, advertisements, and donations to produce and distribute each issue. Please consider donating to our cause, and helping the student journalists of OTR amplify youth voices for years to come.

Kendall Geller is a senior and the Copy Editor for On the Record. This is her third year on staff and she is excited to work with all of the new writers...

Michelle Parada is a senior reporter, this is her second year on staff. She is excited to produce more content and hopes to be a voice to the Hispanic...

Noa Yussman is a senior and the Creative Director for On the Record. This is her third year on staff and she is so excited to help create a visually cohesive...

Anna Burzynski is a senior Photographer for On The Record. She is passionate about taking photos that help capture a story. In her free time she likes...