June 29: BREAKING NEWS. Bold graphic letters slid across my once black TV screen as I held the volume button, increasing the sound of the news. A brunette journalist standing at a clear news desk filled the frame.

“In a 6-3 decision, the justices ruled that Harvard University and the University of North Carolina violated the Constitution by considering race when deciding whether to admit someone to their school,” television journalist Norah O’Donnell said.

My mind was in a frenzy with lots of questions circling my brain. How is this going to change the college admissions process? What is going to happen to college diversity? What does this mean for me as a high school student?

My eyes then shifted to the young protesters projected across the TV screen. They stood outside the courtroom, chanting alongside each other. They gripped colorful signs with phrases in opposition to affirmative action. Some signs read, “Solidarity is power,” and others read, “We won’t go back!”

As O’Donnell continued, I pressed the red power button, removing the image from my screen as the blaring sound faded into the silence of the room.

- • •

While affirmative action was a concept I had heard of before, this decision in June was the first time I stopped to think about what it truly meant. I quickly learned that its complexity was confusing to everyone involved, from college applicants to admissions officers. It seemed as though very few people were able to fully grasp the extent of the decision and its possible effects.

“A lot of people don’t really understand affirmative action, the history behind it, why it was implemented,” said Joshua Williams, associate director of Strategic Enrollment Partnerships at Bellarmine University. “Trying to keep up with it is really hard.”

So let’s break it down.

Affirmative action is a system used by institutions, such as colleges and workplaces, wherein minority groups are underrepresented. It allows those in charge to prioritize minority groups that have been historically disadvantaged.

Universities and institutes of higher education use affirmative action to help diversify their student bodies and campuses. Within this system, colleges consider demographic factors such as race, ethnicity, or gender when deciding to admit students.

In the early 1960s, higher education was limited for people of color, with exclusivity toward white students. However, with contributions during the Civil Rights Movement and activists pushing for change, the need for more minority applicants, specifically Black applicants, became a priority.

As a result, many elite colleges began to adopt policies in order to expand the access of quality university and graduate education. According to the U.S. Department of Education, when institutions first enacted affirmative action policies in the 1960s, Black applicants increased by 83 percent. By the 1970s, Black enrollment in colleges and universities increased by 259 percent.

One way to think about how affirmative action was implemented prior to the most recent ruling in June is through this hypothetical situation: Student A is white and Student B is Black. They have similar GPAs, test scores, class rank, and extracurriculars. In this case, the admissions team could then look at the applicant’s race, and could, if they choose, admit Student B in order to better diversify the school.

This situation depicts race as a “plus factor,” which many colleges use in the admissions process. The plus factor system for admissions quantifies various elements of a student’s application. Before June, this ranking system included race among several other factors. Disadvantaged students got an additional “plus” because of their race. White and Asian American students, who already make up a large percentage of college campuses and are less historically marginalized in educational environments, didn’t get this plus.

Affirmative action took into account what a student did with the opportunities they were given. Not every person has equal levels of privilege due to systemically oppressive factors such as race, wealth, gender, etc. Success looks different from person to person since access to resources and opportunities varies.

Because of decades of slavery, followed by almost 100 years of other legal discriminatory practices, wealth distribution in the U.S. has been historically uneven. It isn’t possible to write off the effects of these practices that have left some students, especially those descended from slaves, disproportionately on the side of lower socioeconomic status.

While the U.S. has a history of discriminatory policies that also target Asian Americans, they have been better represented in college populations. So minority groups that have been historically underrepresented in higher education will be the most affected by the Supreme Court’s decision to ban affirmative action.

“The reason why people seem to think that affirmative action takes away from the merit of people who worked harder is because it’s built on the facade that students have equal access to all opportunities,” said Minhal Nazeer, 18, a Pakistani American senior at Kentucky Country Day School. “And that’s just not true.”

The cycle of students having less access to educational resources still exists, but Nazeer said it’s important to recognize that this doesn’t mean these kids don’t have the potential to flourish in college.

“It’s giving them a chance to succeed with the skills and potential that they had when they weren’t given the resources to do so on their own,” Nazeer said.

- • •

The first major Supreme Court case to define the use of affirmative action in higher education was the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke.

In 1978, Allan Bakke, a white, male student applied to the University of California (UC) Davis School of Medicine. He applied two years in a row, and even though his test scores and qualifications exceeded the criteria for admittance, admissions officers rejected him both times. At the time, the UC Davis School of Medicine had a racial quota, which reserved 16 spots for minority students. Bakke sued, arguing that, as a white man, he was denied admission solely because of his race. The case made its way up to the Capitol.

In Washington, the Supreme Court upheld affirmative action, but ruled in favor of Bakke and held that the school’s diversity quota violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which requires that all people be treated equally under the law, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, religion, gender, and national origin. This decision paved the way for present-day affirmative action, where admissions officers could use race as a factor for admittance, but not through diversity quotas.

“Affirmative action helped diversify the campus, which has been proven to create more well-rounded students,” Williams said.

Williams believes that having a diverse campus has vastly positive impacts for students, noting that a student body from a multitude of backgrounds provides enriched learning experiences, global awareness, and increased tolerance and inclusivity.

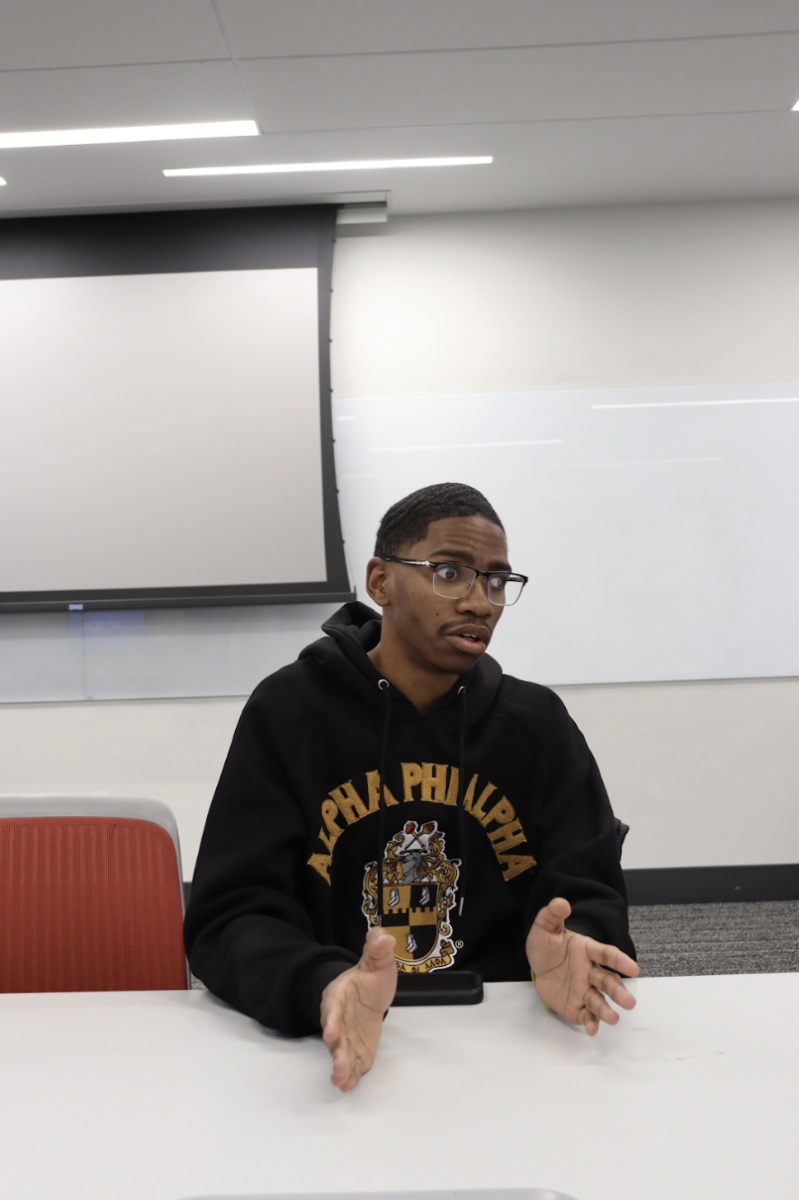

“Diversity is a goal that stretches farther than just having this amount of people on paper as Black, white, Asian, Native American,” said Jayvon Rankin, 20, a Black student at the University of Louisville (UofL) majoring in political science.

Rankin believes that a diverse class unlocks student perspectives and gets people to look beyond their bubble. Without diversity in education, people would be less culturally adept.

“You’re kind of in an echo chamber of the same people,” Rankin said. “You don’t really see the real world.”

This is one argument against eliminating affirmative action in the admissions process — there is no longer a way to easily uphold diversity.

- • •

On June 29, the Supreme Court reversed a decades-long precedent of affirmative action policies. The court said that race, on its own, could no longer be considered in college admissions.

In two lower level circuit courts, a group called Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) sued two universities over their race-based admissions systems. SFFA is a nonprofit group that was founded by Edward Blum, a 73-year-old white male and conservative legal strategist known for his activism against affirmative action. The Supreme Court sided with SFFA, ruling that affirmative action was unconstitutional, altering the way admissions officers review applications.

After reading the court decisions, the cases were still confusing to me and the rest of the On The Record staff, so we turned to our AP US Government and Politics teacher, Tim Holman.

“You basically have to look at the application in a ‘colorblind’ way, and that is something that the conservative majority of the court has been advocating for,” Holman said. “They believe that the Constitution is effectively colorblind, that you should not consider your race at all, whatsoever.”

The “colorblind” argument comes from an interpretation of the Constitution that is based on the idea that, in terms of race, the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment only had slavery in mind. Since slavery no longer exists in the U.S., some argue that the Constitution does not support leveling the playing field on the basis of race. Some see the prioritization of historically disadvantaged groups as unfair and unnecessary in this day and age. So the question becomes, was it too soon to get rid of affirmative action? Are we, as a society, able to be “colorblind”?

“People of color aren’t able to not think about their race or their ethnicity,” said Nazeer. “That’s sort of a privilege white people have over us.”

From the food they eat, the languages they speak, and the physical features they present, people of color are constantly reminded of who they are.

“There were all these different parts that are embedded in American society where race was considered,” Rankin said. “And now 200 and nearly 50 years later, ‘Oh, we just magically can’t use race anymore.’”

Many are frustrated over the ruling and its attempt to create a “colorblind” application process. However, there are still ways race can impact a student’s college application.

On students’ college applications, they can mention activities that allude to race, such as student unions or activist groups. In their essays, they can also speak about their personal experience with race, including obstacles they overcame because of racial barriers, or ways that race has affected their upbringing. So while the admissions officers can no longer consider race as an overall plus factor, they can look at its specific impact on an individual and how that impact might showcase qualities about an applicant that make them desirable. The Supreme Court essentially said that race affects everyone differently, and that as a whole, it is unconstitutional to give an advantage to an entire group of people because they are a minority.

“They wouldn’t know that I was Pakistani, they wouldn’t know if I was bilingual,” Nazeer said, reflecting on her own essays. “And that was just such a weird feeling to me because I’m like, ‘Wait, that’s such an important piece of information that I’m not able to put anywhere.’”

While Nazeer chose not to make race a defining factor in her own essay, other minority students now have to make similar decisions. How much significance do they want race to hold in their application? Since essays are now one of the only ways students can convey their identities, they may box minority students in by making them feel like their essays must pertain to race-related issues.

“It’s super frustrating on our part,” Nazeer said, “but it’s also been kind of helpful for some schools that have been more intentional asking prompts that allow you to talk about those experiences, which has been nice.”

Aside from the “personal statement” essay college applicants write, some colleges also offer additional supplemental essays with varying prompts. With the absence of affirmative action, many schools have now added or altered prompts on their applications to give students the opportunity to talk about how race has impacted them. These prompts may include discussion of background, identity, or the importance of inclusivity.

- • •

To understand what this could potentially mean for college admissions, we can look to the nine states that had already banned race-conscious admissions at public colleges and universities prior to the June decision. One of these states was California.

In 1996, the passage of California’s Proposition 209 effectively banned the use of affirmative action within state governmental institutions, including public universities. So for nearly 30 years, the UC schools have been functioning without affirmative action.

In the immediate years after the removal of affirmative action in California, there was a 12 percent decline in underrepresented groups across the whole UC system. UC Berkeley and UCLA experienced the most extreme effects, with a 60 percent drop in Black, Latino, and Indigenous students, widely changing their student body demographics.

“One of the big problems that the California schools dealt with after they banned race-based admissions was that, increasingly, Black students sort of felt like they were on an island,” Holman said, “that they were always like the one or two or three Black kids in the class.”

However, the decline in diversity was a problem that the UC system, along with other colleges, recognized and decided to take measures to reverse.

“I think we have to find more innovative ways to recruit a more inclusive class without consideration of race,” Williams said.

One way schools are doing this is through targeted minority outreach. This involves going to schools in underserved communities, as well as sending letters and emails to minority students.

Some colleges have also started automatically admitting students if they are at the top of their high school’s graduating class. In 1997, Texas passed House Bill 588, more commonly referred to as the “Top 10 Percent Law.” It guarantees that Texas high school students who graduate at the top 10 percent of their class receive admission to all state-funded schools.

Since many high schools contain students of similar backgrounds, admitting students based on how they perform compared to peers in their own school, rather than schools elsewhere, is one way admissions officers are diversifying their student bodies.

The UC system currently has a similar method in place where they look for California residents who are in the top 9 percent of their graduating class. While students don’t receive automatic admission to the UC schools for being in this percentile, due to space reasons, it does give them a leg up.

These methods, among other efforts, have helped to reduce the diversity drop in the UC system over time, without using race-conscious admissions. In 2021, UCLA’s admitted first year class had similar, even slightly increased, diversity as compared to before Proposition 209. Black students made up 7.6 percent of the university’s population in 2021, as compared to 7.3 percent in 1995. In addition, the Latino student population increased from 22.4 percent to 26 percent.

However, these efforts come at a cost. Over the past 25 years, the UC system has spent over $500 million to help diversify their schools, and while they have had some success, not every institution has that level of funding. Whether or not all schools are able to, or even want to, put in similar levels of commitment, time, and money to diversify is up in the air.

- • •

The reality of the situation is that the ruling is primarily going to affect minority students applying to the most selective schools around the country. This is due to their extremely low acceptance rates that require near perfect test scores, grades, and a surplus of extracurricular activities to get in. The applications these schools are seeing are widely similar to one another in terms of quality, so without affirmative action, it is going to be much more difficult for historically disadvantaged students to get into these prestigious schools.

“Now we all know that those elite institutions are sort of the stairway to power,” Holman said.

He was right. An October report by Opportunity Insights found that Ivy League and Ivy+ students are nearly twice as likely to attend top graduate schools, and are 60 percent more likely to reach the top 1 percent of earners in the country.

With a smaller percentage of minority students attending those institutions, it’s possible to see the effects of this ruling bleed into society at large.

- • •

While institutions are finding new, creative ways to push diversity, it is hard to say what exactly will come from this ruling. The current admissions cycle for students entering college in 2024 is the first since the court ruling in June.

For many students, the future is unpredictable and scary. As a sophomore in high school, I fear what college will look like when it is my turn to apply. That same uncertainty I felt the first time I heard of the ruling still rings true. For now, it’s important to stay educated and aware. In a generation that feels disconnected from government impacts, this ruling affects us.

“We’re still learning how it might impact students of color in Kentucky,” Williams said.

And that response will reveal itself with time.

“We will see,” Williams said. “We will see.” •