Movement.

Just to the left of Bardstown Square, a stretch of road led behind the sprawl of shops to where a trickle of water pooled into a puddle of trash and food.

The car continued down the pavement, searching for any indication of a person.

“There,” said Matthew Feltner, pointing behind the water to a dark green dumpster, where a man’s head peaked above the rim.

Lauren Stokes followed his direction and parked directly in front of the dumpster. The two stepped out of the car, Stokes going to talk to the man, Frank, while Feltner moved to grab a sandwich out of the trunk.

I followed Feltner, surveying the bins, bags of food, cases of water, and folded clothing that filled the back of the car. He grabbed a brown paper bag and jogged over to Stokes, who was coaxing Frank from the dumpster.

He was one of the regulars that the two served on their weekly route for Louisville Outreach for the Unsheltered (LOU), a nonprofit dedicated to supplying the homeless population of Louisville with resources necessary for their survival.

Frank held the bag in his hands as his eyes drifted to the left, where a couple of regulars were making their way toward the car.

Stokes greeted them and handed them both a sandwich. From there, they began catching up like old friends, discussing everything from the weather to the camp clearings all over Louisville.

“Speaking of,” Stokes said, the words sparking a memory, “Have you seen Patrick?”

They shook their heads no.

Stokes sighed, but wished them well as they headed back the way they came.

Once they were out of earshot, I asked, “Who’s Patrick?”

Stokes explained that she had met him on her very first serve back in January 2023, and has served him consistently since then.he is one of the regulars that she’d served every week for almost a year. He’d camped in a variety of locations during that period, usually along Bardstown Road, and had been cleared at least 10 times according to Stokes. It was March 10, and the most recent clearing happened in February when Patrick had been camping behind a dumpster, but since then, Stokes hadn’t been able to find him.

“I can’t find him and I’m worried about him,” Stokes said.

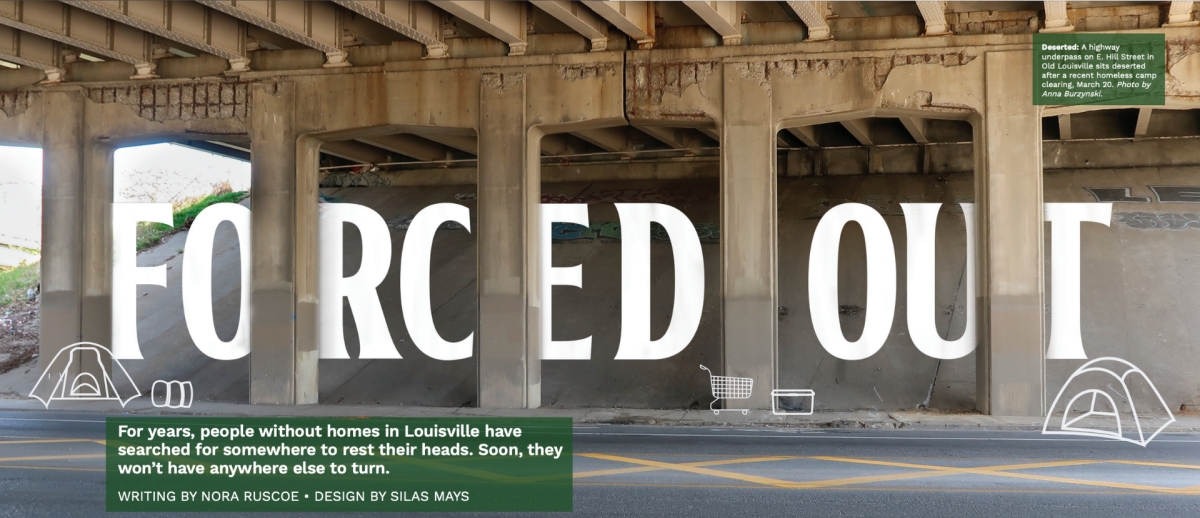

I thought back to a camp I’d seen under the Watterson Expressway. Every morning when I went to school, I would see it, but it wasn’t until it was suddenly gone that I really paid attention.

I’d heard talk that the city removed them for various reasons, but the majority of the clearings came down to appearance.

“It didn’t look good.”

“It was an eyesore.”

After the camp was gone, I found myself glancing out the window every time we passed where it used to be, thinking maybe the people would have returned, but nothing remained except the occasional plastic bag.

When a camp is cleared, it’s assumed that they’ll just go somewhere else, some other patch of grass or hidden spot, but where?

Where could they go if everywhere in the city was under the threat of being cleared?

What made them choose the streets rather than a shelter?

Where could they go, and why weren’t more people talking about it?

Before we set out

The parking lot of Beargrass Christian Church slowly filled with volunteers and outreach workers as LOU’s “primary serve” began. They ran up and down the side stairs in the activities building, dropping off boxes and picking up supplies from the trailer at the far end of the lot.

Amy Nguyen, the donations director at LOU, was in charge of ensuring the trailer stayed clean, organized, and easy to access. Throughout the day, Nguyen periodically set out a big blue tarp with piles of new supplies and tasked volunteers with sorting them. Students from schools like Trinity High School and Sacred Heart Academy donate many of these supplies and get service hours for doing so.

On March 3, I became one of those volunteers. From 1:30-3:30 p.m., I separated shoes and pants according to gender, size, and type.

Even though this experience showed me the importance of having an abundance of resources and volunteers, I still didn’t know the ins and outs of the job. So I decided to come back the next week, but this time, it would be different.

Eviction Notice

On the morning of March 10, a car door slammed as a woman with a bright orange ponytail in a gray sweatshirt, leggings, and boots jogged up the stairs and into the kitchen.

Stokes, the communications director at LOU, smiled and introduced herself before grabbing her designated supplies and loading them into her car. I followed her and climbed into the backseat.

A couple minutes later, a man in a black zip-up and khaki pants slid into the passenger seat, introducing himself as Feltner, a long-term volunteer at LOU.

The two of them drive a route throughout Louisville every week in search of anyone on the streets who may need help or resources. Many of the people they serve are regulars they have distributed to frequently ever since they started doing the route a little over a year ago.

In most cases, their regulars are easy to find, given that they tend to stick to similar spots, usually in camps. Homeless camps are visible structures such as tents, shanties, or shacks where more than one unhoused person lives. To onlookers, they may seem like an eyesore, but to those living in them, they’re home.

The Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) has recently cracked down on the removal of these camps, making it infinitely harder for outreach workers like Stokes and Feltner to do their job.

For more information on the camp removal process, I reached out to Aaron Selbig, the communications coordinator at Louisville Metro Office of Resilience and Community Services. He said that LMPD’s Homeless Services Division (HSD) inspects the encampment and evaluates the level of risk it imposes through a variety of factors — proximity to schools and roadways, number of campers, amount of trash, etc. Then HSD leaves notices around the camp for a removal in 7-21 days. Resource outreach specialists routinely check back with all of the inhabitants of the camp to provide them with “local services and transportation to shelters.”

Once the allotted time is up, most campers have already left, but any remaining belongings or waste are disposed of by the Metro Public Works Department.

This information comes from Selbig, but accounts differ among outreach workers.

“They throw their tents away, they throw their birth certificates away, all of those things that we work to acquire for them,” Stokes said.

She also described a procedure in which those remaining in the camps are picked up and taken to hotels in Louisville. They are allegedly placed there for nine days before being released back onto the streets.

“The nine days sounds like it’s doing a good thing, but it’s really not,” Stokes said. “It’s getting these people used to being back indoors. It’s just enough time to get used to it and then they’re kicked back out on the street.”

When this occurs, outreach workers aren’t notified on where the homeless people are being taken, nor where they’re being released. This affects LOU and other outreach organizations’ ability to find and aid the unsheltered individuals who have been displaced in the process.

Still, Amie Michel, the director of LOU, explained how even though the removals separate the regulars from their normal spots, people often return to what’s familiar.

“Typically, people are creatures of nature, and so we tend to go back to what we know,” Michel said. “So a lot of times they will return to where they were before, where the clearing was before.”

As we continued our route, we stopped at an already cleared camp and picked through the remnants in an attempt to find any sign that someone in need of resources might still be there.

Nothing.

For months it had bustled with activity, but now trash littered the ground and there was no one in sight.

Venturing farther into the remains of the camp, a wave of unease passed over me as I remembered that, on top of the clearings, homeless people would soon face an additional hurdle — with new legislation, they will have nowhere left to turn.

Punishable by Law

The Kentucky Legislature recently passed a law that not only allows LMPD to fine homeless people caught camping throughout the city, but also jail them.

This bill is known as the Safer Kentucky Act, or HB5.

According to state Rep. John Hodgson, a Republican from District 36 and co-sponsor of HB5, the goal of the bill is to reduce violent crime in Louisville.

“Studies show that ½% of the population is terrorizing the other 99.5%,” Hodgson said over email. “And if we hope to have a safe and civilized society, these violent criminals need to be removed from the street until they are no longer a threat to their neighbors.”

However, when I followed up with him to check that his statistics were sound, he couldn’t provide me with any studies.

“These are estimates based on interactions with professionals on the subject, from multiple cities,” Hodgson wrote in response.

However, this is one of the common arguments for why the bill classifies street camping as an act punishable by law. In section 17, it states that an individual is guilty of illegal camping when they knowingly enter and remain on public or private property with the intent to sleep or camp there, with the exclusion of temporarily sleeping in a vehicle.

In other words, any person who knowingly camps anywhere it hasn’t been approved will be written up for a violation on their first offense, resulting in up to a $250 fine. Or, an offender can be given a Class B misdemeanor, which is punishable by an up to $250 fine, up to 90 days of jail time, or both.

The bill does leave room for the judges to provide an alternative to jail, such as relocation to drug or mental health rehab instead of releasing them back onto the streets after their punishment has been determined and served.

“There is no compassion in allowing them to remain living on the street untreated, where they will die 30 years prematurely, and negatively impact the community safety while they are doing so,” Hodgson wrote.

However, this “diversion program” is dealt out on a case-by-case basis, and offenders might not have the resources for representation other than public attorneys, making it more difficult for them to put together a case that doesn’t result in jail time.

When I asked Selbig for a statement on the bill in April, he stated that his department has “not yet been able to closely study the possible ramifications of the Safer Kentucky Act,” and didn’t have any further comments.

However, people at various Louisville outreach organizations voiced their opinions on the topic.

Stuart Walker is the program manager at Sweet Evening Breeze, a nonprofit providing a wide array of resources to LGBTQ young adults experiencing homelessness. Walker agreed that some portions of the bill have benefits, but the drawbacks outweigh them.

“I don’t think it’s fair to add homelessness into a bill that is trying to mitigate violence and murder,” Walker said. “Because one, you’re equating homelessness with violent crime, and then two, it makes it harder to fight that part in the bill that’s about homelessness when you know the other parts of the bill are pretty valid.”

David Smillie, the executive director of LOU, agreed that the bill has its downsides.

“It’s very, very clearly an overly ambitious bill that bundles way too many issues into one package as a sort of cure-all for some sort of real and or imagined safety threats in our state,” Smillie said.

Michel agreed, stating that she didn’t see the logic of the bill, as it would only perpetuate the cycle of homelessness.

“You’re fining someone who doesn’t have any money. You’re putting them in jail for what purpose? Because when they release them, what are they supposed to do?” Michel said. “It’s expensive to keep someone in jail, and you’re not gonna get money out of them. They don’t have money. That’s why they’re on the street.”

Instead, she wished the time, energy, and money spent on it should be put toward programs that would better help the homeless.

On April 9, Gov. Andy Beshear echoed the concerns of the outreach workers when he vetoed the bill for similar reasons. However, the Kentucky House and Senate overruled this veto and the bill was passed into law on April 15. As the backlash spreads, citizens and organizations continue to fight for the homeless people of Louisville.

Housing Not Handcuffs

“What do we want?”

“Affordable housing!”

“When do we want it?”

“Now!”

Stephanie Johnson, emcee of the Housing Not Handcuffs rally, shouted into the crowd. She grew louder with each repetition of the chant until the noise came to a crescendo and died down.

On April 22, the Coalition for the Homeless and other Louisville nonprofits organized a rally outside of the Mazzoli Federal Building downtown in opposition of the passage of HB5, as well as Johnson v. Grant Pass, a case currently being heard in the Supreme Court.

Johnson v. Grant Pass originated in Grant Pass, Oregon, where the city started ticketing people found sleeping in the streets. In 2018, the homeless people of Oregon sued the city, citing the Eighth Amendment in that ticketing and jailing people on the street is cruel and unusual punishment — especially when there aren’t enough safe and accessible shelter beds.

Whether or not legislation like the Safer Kentucky Act and the law in Oregon are constitutional will be determined in late June when the Supreme Court sets the precedent by releasing their decision.

For now, opponents of the Safer Kentucky Act continue to fight for what they believe in.

At the rally, Louisville’s Coalition for the Homeless invited nine speakers from different social and political backgrounds to discuss the issue at hand, including former state House representative and U.S. Senate candidate Charles Booker, and Rep. Morgan McGarvey, current U.S. representative from Kentucky’s 3rd Congressional District.

I moved toward the front, the lull of the crowd dissipating behind me as I focused on the speaker at the podium.

“I want to live in a country where my dignity isn’t tied to where I live or how much I make,” said Dr. Eric French, a preacher at Antioch Missionary Baptist Church. “I want to live in a country where I don’t have to worry about being arrested because I have no place to live. We have the means to address homelessness, we’ve just taken the easy route.”

When the actions of legislators align with sayings like “out of sight, out of mind,” they not only displace hundreds of homeless individuals, but uphold the belief that if the issue isn’t visible, it isn’t there.

“When we talk about homelessness, we discuss it in terms of the homelessness issue. The homelessness crisis. The homelessness problem,” state Rep. Nima Kulkarni said at the rally.

Instead, she urges people to look past the perceived “crisis,” and consider the humans behind the statistics.

“We do not talk about the son struggling with mental illness,” Kulkarni said. “Or the daughter who may have an intellectual disability. We do not talk about the single mother, who is trying to keep her children safe as they live out of their car.”

Although they all went about it in their own unique way, each speech contained a similar message: jailing someone for living without a set address is cruel and unusual punishment. They also agreed that the funding for HB5 should be directed toward outreach organizations and affordable housing efforts.

LOU and other organizations provide for everyone they can, but there are hundreds of people living without housing in Louisville and outreach organizations can only do so much, especially as clearings increase and legislation like the Safer Kentucky Act is put into effect. Since Louisville doesn’t currently have enough affordable housing to solve this issue and Kentucky legislators signed HB5 into law, homeless people are left with just one legal option: shelters.

A Place to Rest

April Morris was homeless for six years, from April 2017 to September 2023.

At first, finding a place to sleep wasn’t an issue because there were many open lots and fields that offered the one thing that city shelters didn’t: privacy.

This notion was echoed among many, including organizers at various homeless shelters like Walker at Sweet Evening Breeze.

“The living conditions are not very private at all, it’s communal,” Walker said. “Restrooms and showers are also communal sleeping spaces, and some people would just prefer to live out somewhere.”

Although it is an important factor, privacy isn’t the only reason homeless people don’t go to shelters — some people do favor sleeping at the shelters, but there isn’t enough space for them to do so.

According to a 2023 survey by the Coalition for the Homeless over 1,600 individuals were either living out on the streets or in shelters in Louisville. As a whole, only about 750 beds are available every night, which means that, should they seek it, over 800 individuals would be denied access due to shelters being at capacity.

“You have to either be in line by 3 p.m. to get into one of those shelters or call by 1 p.m. to reserve a bed,” Walker said. “And with as many people out here experiencing homelessness as there are, you’re not guaranteed a place in the shelter at all.”

As time went on, Morris realized that she wasn’t going to be able to live on the streets forever. During a visit on the street by an outreach organization, Morris began the process of obtaining a housing voucher and has since secured a permanent supportive housing voucher. This means that she has and will continue to have a permanent shelter over her head for the rest of her life. (Scan the QR code if you want to read more of Morris’ story).

Taking it all in

Trees passed in a blur of green as we circled back along the route to the Beargrass Christian Church. Stokes and Feltner started talking, attempting to include me in their conversation, but I couldn’t focus on anything they were saying. My mind remained on the people I had just met. The two hours on the route had come and gone, but the experience was engraved into my memory.

The car pulled into the lot, and I only remained silent for a few seconds before my question spilled out: had Stokes and Feltner been this impacted when they’d gone on their first route?

Sitting in the car, I wondered if Stokes and Feltner had been this impacted when they’d gone on their first route.

In a separate interview, I found out that partaking in the route had completely changed Feltner’s perspective.

“Before I started doing this, I had a misconception that homeless people were people who’d rather do drugs or alcohol or whatever their fix is instead of work,” Feltner said. “This has completely and entirely changed my outlook on that. There’s a ton of good people just like you and I that have had horrible things happen to them, or they’ve had trauma in their lives, and they’ve made some poor choices, admittedly, but they’re dealing with stuff that a lot of us could never imagine.”

Stokes and Feltner have formed connections with the people they’ve served over the past year, and have grown concerned when they aren’t able to find them. Sometimes, it was months before they ever made contact again.

This was the case for Patrick, but luckily, after a little over a month of being missing, he reached out to Stokes to tell her he was okay.

“I talk to him just about every day!” Stokes wrote to me in a later message, relieved that she had gotten in contact with Patrick.

This story began with a question, one that I thought would be easy to answer. But as I continued learning about the topic, I realized that the issue is more far reaching than I assumed. Yes, there are camp clearings and yes, there aren’t enough shelters, but those are just some of the most immediate threats to the homeless population.

State governments across the country have created legislation that aims to restrict their rights even more, and as this topic gains more traction in the government and media, it becomes imperative for everyone to get involved. This can be as simple as donating a pair of outgrown shoes or as proactive as calling your state representatives and expressing your concerns.

“If the highest court in the land overturns this decision, it is up to us, all of us here in our city, in our state, to make sure that we enact local policies that treat people like people, and not like problems to be swept away,” Kulkarni said at the rally. “Housing is a human right.”

Lauren Stokes • Jun 17, 2024 at 4:10 pm

This is truly amazing. Thank you Nora, and Ana, for your time, effort, concern, and compassion. I am so glad to have been able to meet the both of you. You’re going to go so far!